TOWARDS A CLASSIFICATION OF TROPICAL TREE FRUITS, PART II

4. THE POLY-AXIAL SPECIES

4.1 Branching and growth rhythm

The branching of poly-axial species greatly increases the possibility for the individual plant to explore the environment. Giving up radial symmetry the plant squeezes into any openings it finds in the canopy. Therefore the branches trees are suited to row cropping in rectangular patterns, whereas single-stemmed species do much better in equidistant patterns.

Rapid shoot growth is desirable to occupy open spaces as they occur. Vines embody the all-out pursuit of this strategy. Trees are not so flexible, and because of the progressive increase in shoot numbers and leaf area, rapid extension growth cannot be sustained for very long.

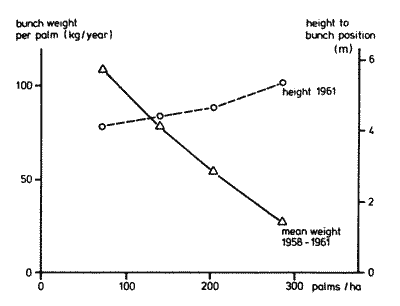

| Illustration 1: Increase in height and steep fall in yield of oilpalm under mounting inter-tree competition (after Cly and Chapas, 1963) |

Table 1: Reports on growth analyses in oilpalm; data after Corley et al (1971) and Corley (1983)

| Crop/Reports | Crop Growth rate | fruit yield | harvest index | LAI |

| ton/ha/year | % | |||

| OILPALM Corley et al (1971) Malaya - adequate moisture | 29 | 12.5 | 42 | 3.61 |

| Ng et al (1968) Malaya - adequate moisture | 28 | 12.6 | 45 | 3.72 |

| Tees and Tinker (1963) W. Africa - moisture stress | 19.5 | 5.2 | 27 | 4.93 |

| Stage of growth | Growth rhythm |

| Seedling | |

| Sapling | continuous growth |

| young tree | frequent, long flushes only a few, short flushes better synchronised more responsive to environmental influences |

| aging tree |

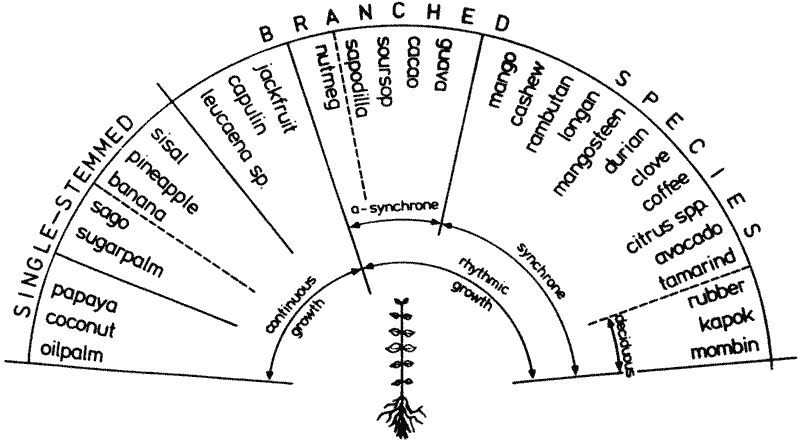

Illustration 2: (above)

Changes in the growth rhythm as trees grow older and branching becomes more complex.

Illustration 3: (above)

As trees grow up, the continuous growth of the seedling gives way to a spectrum of different growth rhythms; these are shown - with examples - in relation to branching habit.

Table 2: Crop duration and yield of irrigated plantain cv Njock Korn grown at two elevations in Cameroon (after Melin, Plaud and Tezenas du Montcel, 1976).

| Altitude: | 80 | 550 | m |

| Crop duration: | 413 | 511 | days |

| Yield: | 45.4 | 53.9 | ton/ha |

| Yield per day: | 110 | 105 | kg/ha |

Presumably that is why branched trees tend to grow rhythmically rather than continuously. The continuous growth of seedlings and the changes in growth rhythm as the tree grows up and branching becomes more complex, supports this view (discussion in Alvim, 1964; Borchert, 1978). Borchert's trials with pruning of saplings indicate that the growth rhythm indeed changes with the complexity of ramification rather than with tree age. Illustration 2 depicts the general trend of changes in the growth rhythm with increasing complexity of the tree. According to Zimmermann and Brown (1971), vigorous but intermittent extension growth 'is more universally competitive, even in the tropics, than a slower sustained pattern of growth'.

The growth rhythm is synchronous when the trees of an entire population flush, flower and fruit more or less simultaneously. In the case of asynchronous growth rhythms, each tree (nutmeg), sector of a tree (often in mango, sapodilla), or individual branch (often in guava), flushes, flowers and fruits in its own time, not in step with other trees or other parts of the tree. Rhythmic growth is a characteristic of the individual shoot; synchrony is a characteristic of the tree population.

The age old controversy over the endogenous or exogenous causes of the observed rhythmic growth of many tree species in non-seasonal climates (see reviews by Coster, 1923, Richards, 1957, Alvim, 1964 and Huxley and van Eck, 1974) can be resolved by clearly distinguishing between rhythmic growth of the shoot and its synchronisation in the population. Working with synchronously flushing species, Borchert (1978) has collected much evidence to show that rhythmic growth is regulated by a feed-back control system between top and root, an endogenous mechanism. During a flush, the top:root ratio rises sharply; in the following quiescent period, the roots can catch up to restore the ratio, whether root growth is accelerated as in cacao (Kummerow et al 1982) or not, as in rubber (Halle and Martin, 1968). Such an endogenous cause can explain synchronous flushing within a tree, but synchrony within the entire population can only be attributed to exogenous stimuli. The fact that synchronous growth rhythms - including synchronised leaf change as in rubber - are found throughout the tropics, implies that there are no truly equable climates! Weak climatic stimuli may be amplified if they effect simultaneous flowering (e.g. a shower in coffee, a few weeks dry weather in durian); the resulting fruit load checks vegetative growth and thus emphasizes the synchrony.

Klebs (1917) already stressed that every climate provides stimuli affecting the growth rhythm, in order to support his contention that rhythmic shoot growth as such, not just its synchronisation, is caused by the environment. Although in his trials the flush was extended and/or shifted by environmental factors, shoot growth remained rhythmic, whatever the succession of experimental growing conditions. The conclusion should have been that the environment can only modify the expression of rhythmic growth; the phenomenon, as such, is endogenously controlled. In fact the prolonged flushing under favourable soil conditions and in pruning treatments (reduced branching) which Klebs reports, fully agrees with Borchert's top: root feedback hypothesis.

Climatic stimuli in the tropics are both weak and erratic in comparison with the summer-winter contrast at high latitudes. Thus the shoots are exposed to faint and fickle stimuli, and these are further dampened by the soil before they reach the roots. The overall effect on the top:root feed-back system may be marginal in many instances. This helps to explain why asynchronous rhythms are widespread in non-seasonal climates. The age of a branch and the corresponding roots, fruitfulness of the branch in the previous season and spot differences in soil conditions may all play a role in the expression of asynchrony. In a perfectly equable climate all rhythmically growing species should revert to asynchronous rhythms! For many species this has been reported (Koriba, 1958). Experiments in growth cabinets are needed to further clarify rhythmic growth phenomena, also in relation to top:root ratio.

Continuous growth in branched species is generally not steady as in single-stemmed species; often rhythmic fluctuations in growth rate can be observed. Tell-tale signs are: a few short internodes and/or smaller leaves and abrupt changes in bark colour, occurring at intervals along the twig (Koriba, 1958). Hence Borchert (1978) contends that continuous growth in branched species is not essentially different from rhythmic growth; both presumably are affected by oscillating top:root ratios.

Illustration 3 shows the different growth rhythms in relation to branching. Examples of asynchronous and synchronous growth rhythms have been placed under the rhythm under which they are assumed to be most fruitful.

4.2 Branching and flowering/fruiting

The proliferation of growing points in branched trees, with their extreme variation in shoot vigour and disposition, deprives flowering of the well-defined place it has in single-stemmed species (Corner, 1949). In evolutionary terms: branching shifts the emphasis from survival of the species to survival of the individual.

Thus it is common for branched trees to have a long juvenile phase - often 5 to 10 years - and to flower poorly and erratically. As a result, the yield levels are generally well below those of successful single-stemmed species, and they vary so much from tree to tree and year to year that it is virtually impossible to set normative figures.

The contrast between single-stemmed and branched trees with regard to flowering and fruiting is indeed striking. Where the environment and husbandry are conducive to vegetative growth, the yield of single-stemmed fruit crops is predictably high; neither yield failures nor excessively high yields are to be expected.

In the branched fruit crops on the other hand, the grower has to strive for a balance between vegetative growth and flowering/fruiting. The low and unpredictable yields cannot simply be improved by promoting growth. On the contrary: more often than not measures such as irrigation, manuring, etc. stimulate growth at the expense of flowering and fruiting! This is the reason why farmers often neglect their branched fruit trees, even while tending other crops carefully. Nevertheless some trees in some years flower and fruit excessively, which is detrimental to fruit quality, tree vigour and fruiting in subsequent years.

To improve the balance between growth and fruiting in branched trees manipulation of the trees should precede manipulation of the growing conditions. Trees can be manipulated by:

- • vegetative propagation to eliminate the juvenile phase,

- • girdling to modify the top: root feed-back control,

- • bending and pruning of branches to change the distribution of growth over the tree and promote flower initiation,

- • defoliation to synchronise the growth rhythm,

- • fruit thinning to avoid biennial bearing.

Only where crop manipulation has greatly improved the balance can a favourable response to irrigation, manuring, etc. be expected. Along these lines, spectacular improvements in fruitfulness have been achieved in some species: apple, pear, grape, citrus, avocado; incidentally also in loquat (Assaf and Rivals, 1979), mango (Bondad, 1983) and guava (Shiguera and Bullock, 1976). This points the way towards recovering a much larger part of biological yield in the form of fruit in other species also. Hence research priorities in branched fruit crops are not the same as in the single-stemmed crops. Fertilizer trials in mango for instance make no sense until a fair balance between growth and fruiting has been achieved.

DATE: July 1986

* * * * * * * * * * * * *