COPING WITH CYCLONES, PART I

INTRODUCTION

When the notorious North Queensland explorer and adventurer Christy Palmerston was mapping a railway route from Innisfail to Herberton, he travelled through the luxuriant rainforest of the Palmerston area, between the North and South Johnstone Rivers. This area was not yet settled, and in fact, this explorer was one of the first Europeans to see this part of the tropics. In his diary of 1882(1), he wrote, "The soil is deep and rich chocolate colour ---- I passed over places where there was not a tree - one mass of vine interwoven and twisted in all directions; the bamboo cane being exceedingly hard and the scrub knife ringing in the vine, and flying from it just as if it was wire."

Places where there is not a tree do not normally exist in this densely rainforested area, and Palmerston's finding, I believe, was a good description of the scrub devastation that had occurred after a severe cyclone. More recently, in the hills around Babinda, one can still see similar patches of flattened scrub caused by the 1956 cyclone where no tree regeneration has taken place during the last 30 years. Again there were similar areas going to emerge from Cyclone Winifred. In the Innisfail district there were many Aboriginal bora grounds of an acre or more in the middle of dense rainforest. Certainly Aborigines did not appear to have the necessary tools to clear virgin rainforest. I believe that there may have originated from patches of cyclone damage that may then have been further cleared or burnt.

History shows, I believe, that severe cyclones are a feature of the tropics. We must learn ways to cope with them as best we can. Cyclone Winifred was not a one-off event and the next one could come at any time.

FREQUENCY

The frequency of cyclones that would have a severe destructive effect on fruit trees in North Queensland is impossible to determine, for the reason that enough records have not been kept to know how strong the winds were. Even in 1986, we do not know what the lowest pressure was of cyclone Winifred and what the strongest wind speeds were! Accurate, official meteorological instruments are only kept in the major provincial cities.

In Innisfail, a well-kept and calibrated wind gauge was found stuck on 250 kph afterwards, and well-maintained barometers registered as low as 942mb(2). These figures are not official however, and will never be accepted as such. Recording deficiencies such as these are found with most cyclones, and we can never know what the true history of any area has been in the past. The following list is a conservative one, of those cyclones similar to Winifred, that probably would have had a severe destructive effect on a fruit tree orchard in the period of recorded history from 1867 to 1986, a period of 120 years.

In North Queensland during the last 75 years, in anyone region, a cyclone crosses from the sea over the coast about every 4 - 5 years. Certainly, during the last 120 years, some cyclones (**) have been worse than Winifred. The most common time of the year for them is January to March, but they also occur from November to May. Wind speeds of 150 to 250 kph occurred in most of the above cyclones with barometric pressures in the region of 945 to 965 mb. There are many other occasions however when less severe cyclones would have caused significant damage to fruit trees.

| Cooktown | 1876 | Innisfail | 1890 | Bowen | 1867 | |

| 1899** | 1911** | 1870 | ||||

| 1907 | 1913 | 1884 | ||||

| 1918 | 1903 | |||||

| Mossman | 1911 | 1934 | 1958 | |||

| 1920 | 1956 | 1959 | ||||

| 1934 | 1986 | |||||

| Mackay | 1888 | |||||

| Cairns | 1878 | Cardwell | 1882 | 1898 | ||

| 1906 | 1890 | 1915 | ||||

| 1911 | 1934 | 1916 | ||||

| 1913 | 1918 | |||||

| 1927 | Townsville | 1867 | 1979** | |||

| 1934 | 1867 | |||||

| 1956 | 1870 | |||||

| 1986 | 1876 | |||||

| 1890 | ||||||

| 1896 | ||||||

| 1903 | ||||||

| 1956 | ||||||

| 1971 | ||||||

FOREWARNING - Long and Short Range

Banfield's classical descriptions of life on Dunk Island at the turn of the century include a chapter on the 1918 cyclone. This is a most entertaining and engrossing commentary which I suggest everyone read. He makes a few remarks on the animal life which appeared to know that an unusually big blow was coming, and also on the weather patterns in the preceding months.

'Ten days before the second storm, while the sky was cloudless and the air serene, a change in the quality of the heat was felt. During the first three months of the year, the period of heavy rainfall - the temperature is generally humid. Suddenly it became dry and burning, with a tingling intensity, as rare as uncomfortable.'

The records of experienced and competent observers preserve proof that birds and other creatures are endowed with sensibilities so much more acute than those of human beings as to seem by their actions to forecast changes of the weather. It may, therefore, be reasonable to attribute to snakes, as well as to birds, the faculty of prevision of so great a storm before indications of its approach were given by the barometer or were perceptible to human beings. Such a theory, indeed, has the support of facts. Lesser frigate-birds rarely visit this part of the coast save in advance of foul weather. Ten days prior to the event a large flock appeared, wheeling high up in the sky. These, or others of the species, were seen each day until the morning of the outbreak, and reappeared in diminished numbers the day after. Immediately after the storm it was evident that many land snakes had been killed, bodies being seen among the long ridges of rubbish on the beaches. For two weeks prior to the event, quite a number of reptiles known to the blacks as "Wattam" congregated about the poultry yard.... Subsequently, reflection on the invasion provoked the theory that possibly the snakes had an instinctive premonition of the disturbance. Lesser frigate-birds did give warning. Is the most subtle of the beasts of the field to be denied so beneficial a faculty? Not a single specimen has been since, and it is likely that snakes of such habit would be serious sufferers during a whirl of limbs and branches, and that birds generally would ultimately benefit by the destruction of many enemies.' (5)

Prior to Winifred, I remember distinctly that many of the elderly patients of mine were telling me that they did not like the oppressive heat of the summer, which they were feeling much more than usual. Many of them told me that this was the kind of weather which preceded a cyclone. Oceanographers had also noted that the temperature of the Coral Sea waters was about 1.5 degrees C. above normal and that this amount of energy increased the risk of a severe cyclone.

In parallel with Banfield's experience, I also had 5 or 6 patients telling me of finding snakes entering their houses in the 2 months preceding Winifred, both in town and on farms. This is far more than the usual incidence of snakes in houses, My wife noticed that ant activity was high during the week before Winifred, but that by the Saturday morning about 12 hours before the cyclone struck, all ants appeared to have gone. It may be that careful observation of unusual behaviour in the animal kingdom may give many days forewarning of an impending cyclone.

Weather forecasting is able to give advance warning of cyclones, and usually at least 6 to 12 hours warning may be expected. There is no excuse for anyone these days not to be familiar with the signs of an approaching cyclone. Short range forewarning should always be available.

Two distinct problems arose with Winifred however, which caused considerable confusion and fear. Firstly, there was a general opinion in the Innisfail district that the weather reports were about 2 hours behind what was actually happening. While radio reports warned that the cyclone was going to cross the coast later in the evening, it had already crossed. Secondly, we did have adequate warning that the cyclone was a severe one and that winds were destructive with gusts up to 220 kph expected. What we did not know was what winds like that would do, and what 220 kph really meant, let alone winds of 250 kph or more, which is what apparently happened.

AN HISTORICAL ANECDOTE

One of North Queensland's largest ever horticultural enterprises was the Cutten family's selection at Bingil Bay. From 1886 they expanded their family business to include 100 acres of coffee, a timber mill, citrus, banana, pineapple, mango, coconut, and tea plantations, other mixed tropical fruits, a coffee mill and a shipping wharf. At times, they employed over 100 labourers. They endured three cyclones in 1890, 1911 and 1913. Each of these cyclones caused severe damage to their plantations, but they recovered. Other setbacks included a five-month drought in 1902 and the privations of the World War 1. The 1918 cyclone totally destroyed their house, wharf, all buildings and all plantations. Forty years work was obliterated in a few hours. From this there was no recovery. (6) In the Mission Beach district, about fifty years passed before other tree crops were planted. Most of these have now been destroyed by Winifred!

NATURE OF DAMAGE

The tree damage from a cyclone is from a combination of factors including soft wet soil, strong wind, physical disruption of the trees above and below the ground, leaf and bark damage from flying debris (branches, twigs, sand, other objects). Wind damage to leaves prevents them from their normal control of evaporative water loss.

Transpiration through damaged leaves cannot be maintained by the damaged root system. Branches and trunks are broken, split, and cracked. This allows further dehydration and disease may enter. Trees lying down may suffer severe sunburn damage to their trunk and limbs. Root systems are exposed to varying degrees, and even many roots that are still in the ground are ruptured and bruised. Some trees that are pot-bound when planted, never develop a good root system. These trees pull right out of the ground. In many cases, the full extent of the damage is not evident. For months after Winifred, growers were reporting that some of their trees suddenly died. Others saw cracks appear in the bark of trunks near the ground, on trees that did not appear to be damaged before.

REPAIR OF DAMAGE

In many cases, the damage is so severe and widespread that sheer lack of manpower to tackle the huge task prevents the application of proper restorative techniques as outlined here. Broken, split or cracked seedling trees should be cut back below the damaged area with an angled cut to allow water (to drain off), and then painted. Regrowth, if it is going to occur, will be evident within a few weeks. With a grafted tree, if the break has occurred below the graft, treat as a seedling and topwork the new growth, or plant a new tree. If the break has occurred above the graft, trim off the damaged portion.

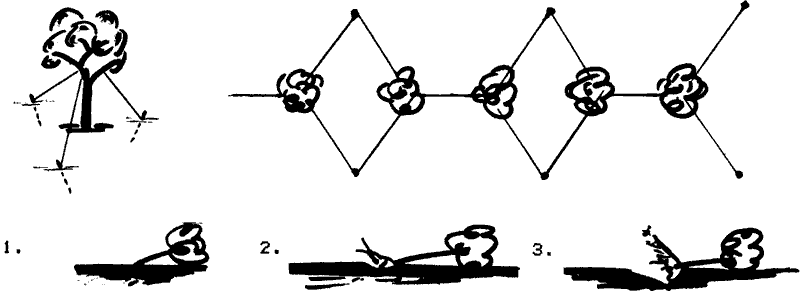

Trees lying down with some root system intact should be lifted up and anchored in place, preferably with several stays so that little tree movement is possible. It is very difficult to dig the roots back in to the ground, and some extra soil is often needed to cover the roots satisfactorily. The rope stays would normally be needed for a few years, so a good quality rope should be used, and these should be tied as high up in the tree as possible, to large branches, and not to the main trunk. Choice of stakes varies, but lengths of 12mm iron bar and half-lengths of star pickets are as economical as anything else. They should be driven at least 75cm into the ground and far enough away from the tree to give a good leverage effect.

Trees should be pruned back to smaller or larger branches and not to the main trunk, using the following guidelines.

1. Trees lying down with root systems mostly in the ground -- 25% to 50% pruning.

2. Trees lying down with some root system exposed - 50% to 75% pruning.

3. Trees lying down with considerable root damage and exposure - 80% to 100% pruning.

Tree trunks should be given sun protection if it is considered necessary. Fertilizing, (particularly solids) should be withheld for a few months, and water stress should be avoided by giving frequent irrigation. If major branches are broken off or have to be removed, then the branches on the other side of the tree may also have to be removed to balance tree shape. It may even be necessary to prune good branches. The overriding necessity is that the tree should be left with an above-the-ground size that relates normally to the size of the effective below-the-ground root structure. All tree wounds should be painted with a paint or bitumen compound. Past experience has shown that if trees are treated like this, many of them will recover well.

After some time, the pruned branches begin to shoot, further trimming of some of the regrowth is needed. Only those shoots which will give the desired tree structure should be retained.

DATE: May 1986

* * * * * * * * * * * * *