INNOVATIVE THINKING

INTENSIVE CROPPING

In the following are presented some arguments in favour of closer planting.

Orchard trees have traditionally been planted around 7.6 - 9 m (25-30 ft) apart, although closer plantings are now becoming more popular. Closer planting, although more costly per unit area, gives a quicker and higher initial return on invested capital. In the cyclone-prone north, closer plantings coupled with suitable windbreaks also result in less wind damage, as we recently observed in Colin Gray's Rambutan orchard.

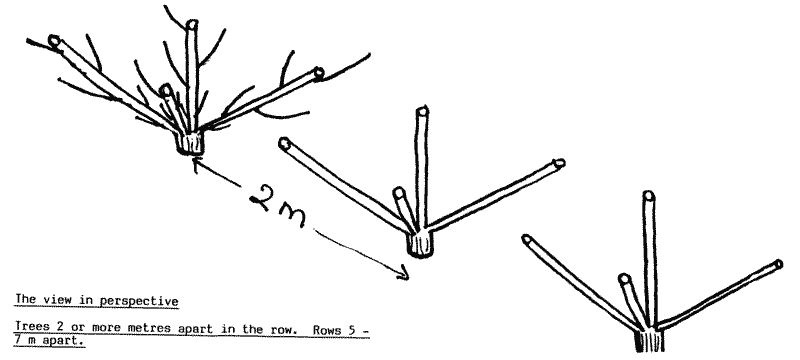

An extreme example of intensive cropping would be apples close-planted in a 'meadow orchard' about 0.6m (2 ft) apart each way in beds as trialled in the U.K. Nearer to home is the considerable work done in recent years with temperate fruit crops in our southern states. The Tatura Trellis is a classic example of an efficient and productive intensive cropping system, especially of stone fruits. Trees are planted 1 - 2 m apart in rows 6 m apart and trained on a trellis. Becoming more popular now are free-standing trees without the expensive trellis but still 2 x 6 m apart.

Practical experience over the years has proved this system of intensive cropping to be very profitable, but a lot more attention has to be paid to irrigation, nutrition, pruning and the use of management tools such as the growth regulant, 'Cultar'.

For the commercial grower, once you have to get up a ladder to pick fruit, your costs of picking go up enormously. Intensive cropping allows picking from mainly ground level, and it is so much easier, as all the fruit is in one plane along a sort of hedgerow.

Fruit more or less in one plane allows the use of mechanical picking aids such as the Australian-made "PLUK-A-TRAK for harvesting apples (or cocoa pods?) and the fruit picking platform now in use in apricot orchards down south. The latter was designed, with the growers, by the South Australian Institute of Technology. Perhaps this could be used for the higher-growing trees such as Matisias and Mamey sapotes. It has been proved to be eight times faster than ladder picking.

In essence, what I am suggesting is that we apply the innovative thinking that has gone into tree fruit production down south to our tropical fruits here in the north. Don't be hide-bound! There is a lot of excellent technology which, with some modification, could be readily applied to tropical crops to improve yields, fruit quality, ease of management and profitability.

With more intensive cropping systems, orchards need not be so large, with their attendant high costs of upkeep. Less mowing and under tree weed spraying. Better use of mulching materials and more efficient use of pest and disease sprays and biological control methods.

Sticking the neck out a bit - perhaps new crops such as intensively-managed cocoa could be a proposition as an additional crop to sugar cane along the coastal areas. Always providing proven, high-yielding varieties are available, that it is not prone to cyclone damage, not affected by fungal wilts or nematodes and the crop is in sufficient demand by the manufacturers at an acceptable price to the grower and we can compete with cheap foreign imports etc. etc. the usual story!

With intensive cropping systems, you would have to pay a lot more attention to the type of planting material and to pruning.

PRUNING

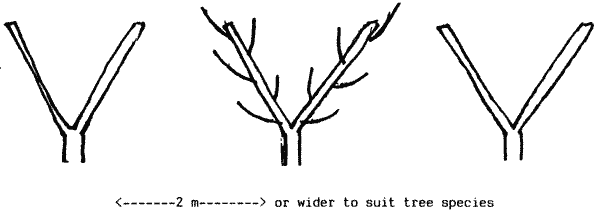

What governs pruning is whether the tree fruits on new wood, as in Carambolas, or on the previous growth flush as in Matisias and Mamey sapotes. I guess Carambolas could almost be grown as a hedge, but for the latter two fruits, pruning in close-planted rows would aim initially at developing four or six scaffold limbs near soil level, depending on planting distance along the row.

Subsequent pruning would be aimed at redirecting vigour into potential fruit wood in the right place, not into unwanted lateral growth and water shoots, and into laterals and leaders required for good tree shape.

To some degree, of course, close planting tends to control excessive vigour because of competition. Crop load also controls vigour.

|  |

| Tree shape for close planting, side view. | End view, showing branch angles. |

The tree crotch to be formed close to ground level to bring fruit wood and crop within easy picking level initially.

|

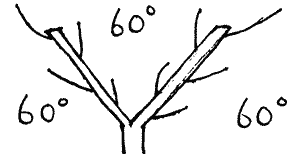

| Rows running north-south with a 60° angle in the crotch of the tree gives the best exposure of leaves to sunlight. |

This shows four scaffold limbs, two each side, per tree. Six or even more limbs could be built in depending on the planting distance and tree species.

Renewal pruning once the tree is mature should keep the size in bounds by removing old and spent wood, replacing it with new wood from a lower level. Whether this is practical with all or only some of our tropical fruits remains to be seen. Coffee, for example, is hand-pruned this way overseas so that picking can be carried out from ground level.

With fruit trees, it may be necessary to allow the trees to develop higher canopies for a larger fruit-bearing surface, depending on the species. But the picking aids previously described enable fruit to be picked up to 3-4 m high.

CLONAL MATERIAL

Regular cropping and high yields are ensured by planting the right trees in the first place (grafted trees - not seedlings). The trees must have the potential for high yield. It would be absolutely essential to plant only proven high-yielding clones or varieties producing fruit of a quality in demand by the market and grafted on selected rootstocks to guarantee performance.

A tall order, perhaps, with some of our tropical fruits, but not impossible. You may even have to grow your own trees. But if you do all this the rewards are ultimately there. Beware: if you plant rubbishy trees in the first place, you've got them for the next 50 years! Get it right first time.

ROOTSTOCKS

A tremendous amount of research work has been done with rootstocks for temperate fruit trees and vines. Once the correct rootstock is identified for any given situation, the cropping capacity is largely predictable. A much better response to management practices such as fertilizer applications and irrigation is assured.

Rootstocks are selected for their resistance to soil-borne diseases and nematodes etc., for their inherent vigour to overcome certain adverse soil conditions or for their dwarfing effect (as in close-planted apples), their ability to obviate biennial bearing tendencies and their influence on fruit set. All these advantages of a good rootstock can ultimately result in consistently high yields and much improved fruit quality throughout the life of the tree.

The type of rootstock used is extremely important in temperate tree fruits, whether it is for a single tree in a backyard or a commercial orchard. It is high time the same sort of thinking went into rootstocks for tropical fruits.

Providing it is looked after properly, the use of the best selected rootstock will guarantee the performance of that tree for the rest of its life. Grafting onto any old seedling is not the way to go. A certain planting of Sapodilla comes to mind where there is a great deal of difference in vigour between trees, due perhaps to variation in seedling rootstock vigour.

Rootstock seedlings from parent trees of known provenance and selected for their vigour and eveness of growth would give a far more predictable performance once planted in the orchard.

Going one stage further, it may be necessary to vegetatively propagate some rootstock clones by cuttings or even tissue culture in order to obtain the sort of guaranteed performance necessary for commercial plantings, especially where high capital cost is involved. There are plenty of examples of the latter in temperate fruits.

THEORY AND PRACTICE

Putting theory into practice in my own backyard, I have had problems with tomatoes, tamarillos and naranjillas, some or all being affected by the soil-borne diseases bacterial wilt, Phytophthora collar rot and root-knot nematodes. None of the fruits survive in my garden without the appropriate rootstock.

The Devil's apple (Solanum torvum) solved all these problems when used as a rootstock for tomatoes. Just a few plants produce buckets of fruit.

For the tamarillo and naranjilla, I use the vigorous rootstock Solanum macranthum, the potato tree (it has flowers like the potato plant). All are of the same family, Solanaceae, and easily approach or cleft grafted.

Both tamarillo and naranjilla grow exceptionally well on this rootstock. At the time of writing, beginning of August, there are lots of fruit on the naranjillas but none on the tamarillos, as very few flowers have appeared so far, although there is a lot of vegetative growth. Some of the first fruits to form on the naranjillas are only just beginning to colour up.

To this end we are also conducting an experiment at the Cairns Botanic Gardens to induce vigour into the weak growing OKARI nut (Terminalia kaernbachii) by grafting it onto the more vigorous rootstocks, Terminalia sericocarpa and T. catappa.

SUMMARY

In summary I would suggest we have a closer look at two things:

1. That tropical tree fruits may benefit from some more innovative thinking. Let us extrapolate from lessons learnt in the management of other tree crops.

2. That clonal selection is more important than seems generally realized at present amongst members. I think we could be more active in the selection and identification of improved clonal material for both fruit production and rootstocks, especially amongst some of our newer rare fruits. The Cairns Branch have begun to do this with Matisias.

The whereabouts of Selected Source Trees, many of them just seedlings, should be carefully identified and recorded and propagation material more widely-distributed to the ultimate benefit of all members.

DATE: September 1991

* * * * * * * * * * * * *