ESTABLISHMENT AND PROPAGATION OF HIVES OF NATIVE STINGLESS BEES

FOR ORCHARD POLLINATION

SUMMARY

Many of the species of fruit and nut trees currently gaining popularity in tropical Australia require insect pollination.

Stingless bees are well-known pollinators of tropical and subtropical plants. The common stingless bee of east coast Australia, Trigona carbonaria, may be managed for orchard pollination. Colonies can be removed from hollow trees and transferred to wooden boxes. Colonies generally thrive in these hives, the population expands and the brood chamber establishes in the centre of the box. If the box is constructed of two equal halves that separate horizontally, the colony can be split by pulling apart the hive and coupling each half with an identical empty half-box. The ability to propagate hives of stingless bees greatly increases their potential for crop pollination.

INTRODUCTION

Trigona is a large genus of highly social bees that occurs in most tropical and subtropical parts of the world. Studies have shown that Trigona bees may be responsible for the pollination of macadamia, mango, lychee, carambola, jackfruit, breadfruit, monstera, vanilla and choko. Other fruits that require insect pollination and could well be pollinated by Trigona bees include acerola, avocado, cherimoya, cocoanut, coffee, feijoa, guava, jujube, loquat, papaw, mamey sapote and white sapote. Many spices such as nutmeg and cardamom, many vegetables such as onions and carrots and many pasture legumes also benefit from insect visitation and are candidates for pollination by stingless bees.

Furthermore, hives of these bees may be transported to temperate areas during flowering times and be used to pollinate such crops as kiwifruit, strawberries, stone fruits etc. Although stingless bees of the genera Trigona and Melipona have been kept by indigenous people of central and southern America for centuries, growers have had to rely on field populations for pollination of their crops.

Trigona carbonaria Smith is the common stingless bee of east coast Australia. It naturally nests in hollow trunks and branches of trees. This paper describes a method of transferring colonies of T. carbonaria from nests to boxes and of propagating the resulting hives by splitting them into two daughter hives. The enhanced availability of transportable hives of these bees increases their potential as crop pollinators.

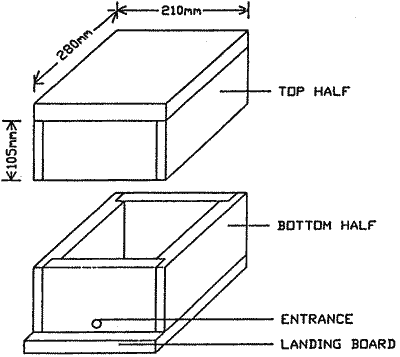

| CONSTRUCTION OF THE BOXBoxes are constructed by building a solid wooden structure which is then sawn into halves. (Fig 1). The given dimensions have proved to be ideal, larger boxes are less conducive to colony establishment and growth. Oregon pine (Douglas fir) timber is recommended as it is light, durable and provides good insulation. Timber of 25 or 30 mm thickness should be used. A good quality glue should be used to fasten the hives parts to each other. Galvanized nails should be used to nail the hive parts together. An entrance hole of 1.2 cm diameter should be drilled into the bottom box. The bottom board may be extended to provide a landing platform. Only the outside of the box should be painted; the bees quickly coat the inside with resin. The joints of the box may be sealed with beeswax. It is important to manufacture as durable a box as possible as the colony cannot be easily relocated to another box if the old one deteriorates. |

| FIGURE 1 A BOX SUITABLE FOR HIVING T. CARBONARIA AND SPLITTING THE RESULTING HIVES. |

Stingless bees have a number of benefits over honey bees as managed pollinators of crops:

- They are stingless and therefore pose no threat to people or animals.

- They may be more efficient pollinators than honey bees of some crops.

- They are adapted to tropical conditions where honey bees may not thrive.

- Hives are small, cheap and easily handled.

- Hives are maintenance free and are not known to become queenless.

- Hives can be easily closed when orchard is sprayed with insecticides or fungicides.

- Keeping of a native bee species is a form of nature conservation.

- They make excellent 'pets', and are an endless source of fascination to children and adults alike.

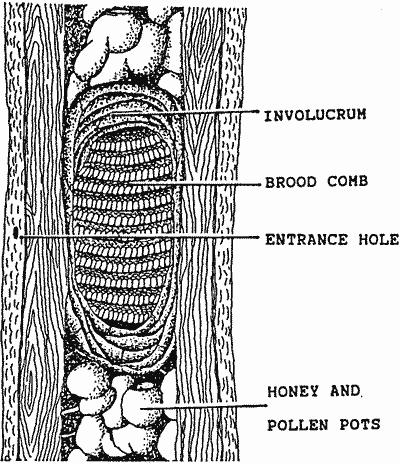

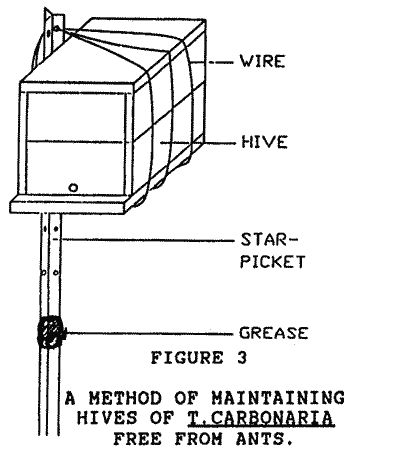

TO TRANSFER A NATURALLY-LOCATED COLONY Most of the nest consists of pillars and columns forming a network that houses large pots (about 1 cm in diameter) of honey and pollen. Towards the middle of the nest is the brood chamber surrounded by an involucrum, or multi-layered sheath (Fig. 2) This structure is quite different in appearance from the storage pots; it is lighter in colour and consists of much smaller and more regular cells. Cut the brood chamber with its involucrum away from the remainder of the nest and place it in the box. Resist the temptation to put the stored honey and pollen into the box, bees drown in the honey and fungus invades the pollen. Until the hive is established, it is necessary to protect it from predators such as ants. Seal the box with masking tape and place it in a position safe from predators. For example, hives may be wired to star pickets that have a greased section (Fig.3). If the hive is left in the vicinity of the original nest the bees collect material from the nest and transfer it to the hive at their own pace. The hive should be placed in a sunny but sheltered position. The bees will find the new entrance more easily if you transfer some of the wax surrounding the original entrance to the new entrance. |  |

| FIGURE 2. A SECTION OF A LOG CONTAINING A NEST OF T. CARBONARIA. |

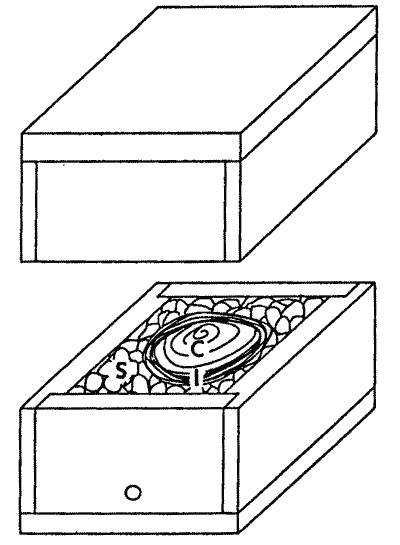

| TO SPLIT THE HIVE As Trigona colonies possess only one queen (Michener 1974), a new queen must be formed in one half of the split hive. The method of caste determination is little understood for this genus. Larger queen cells are regularly seen around the edge of the brood comb, and because of the high success rate of splitting, it is assumed that queen cells are always present in the brood chamber and there is a high probability that they will be present in both halves of the split hive. SWARMING |

| FIGURE 4. A HIVE OF T. CARBONARIA SHOWING BROOD COMB (C), STORAGE COMB (S) AND INVOLUCRUM (I) |

THE ROLE OF THE ORCHARDIST The first step, that is actually locating nests of bees in the wild, may be the hardest. If you live near an urban area, you could contact any local tree loppers and ask them to let you know when they encounter a nest in a tree they are removing. If you live in a rural area, you might like to contact any local foresters or timber-cutters and tell them of your needs. If an area is being cleared in your district, try to arrange to inspect the fallen timber before it is burned. The initial stages in colony multiplication are slow, and so the sooner you begin, the better. |  |

DATE: September 1988

* * * * * * * * * * * * *