POLLINATION AND POLLINATION MANAGEMENT IN ORCHARDS

Address to the First Exotic Fruits Seminar in Mackay, 1987

PART I

INTRODUCTION

In the old testament GENESIS 1:11 it reads that on the third day of creation the earth produced vegetation, various kinds of seed-bearing herbs and fruit-bearing trees with their respective seeds. On the sixth day God created man in his image, he created them male and female. This is the first mention of sexes, in three days after the creation of plants.

This apparently simple text created a mental block and religious belief that there was no male and female in the plant world.

Before 1676, there were only two recorded suggestions that plants may have been male and female. Both THEOPHRASTUS in the third century B.C. and PLINY THE ELDER in 79 A.D. vaguely suggested that palm trees (possibly date palms) had separate male and female trees, and that the female would not bear fruit without a male nearby.

In 1676, SIR THOMAS MILLINGTON announced a theory that flowers had male and female parts.

In 1694, RUDOLF JAKOB CAMERARIUS in his "EPISTOLA de SEXY PLANTARUM" published the first evidence of male and female parts of flowers. His work was based on castor oil plants and maize.

In 1721, PHILIP MILLER FIRST RECORDED INSECTS (bees) as pollinators of plants (tulips).

In 1735, JAMES LOGAN first recorded wind as a pollinator (maize).

Carl van Linne (LINNAEUS), in 1735, wrote Systema Naturae - an outline of classification of plants by their reproductive organs. At this time there were many systems by which people were trying to name, group and classify plants, animals and just about anything else. In 1753 Linnaeus in his SPECIES PLANTARUM commenced the naming of plants by the binomial principle. This is still the basic method used today.

In less than 310 years we have learnt all we know about male and female parts of plants and the importance that methods of pollination play in producing the foods we eat.

PART II

POLLINATION

The Importance of Pollination

Most fruits will not set an economical crop without adequate pollination of their flowers.

Correct variety selection, cultural management and pest control will not give their full return if the flowers don't get compatible pollen. Good pollination can result in higher yield, earlier harvest and fruit of a high quality.

Pollination

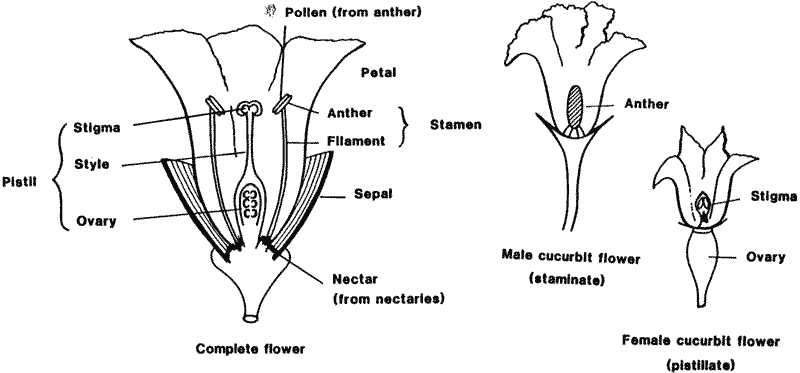

Pollen is a dust-like material. It is produced by the anthers (male parts of the flower). The female, which are usually the fruit-producing parts of the flower, are called ovaries. Protruding from the ovary is the style, on top of which is the stigma. Pollen lands on the sticky surface of the stigma and germinates. The germinated tube grows down the style to allow the pollen nuclei to reach the ovary and fertilize it.

There are numerous pollen grains of many plant types in the air. If the pollen from an incompatible plant lands on the stigma it will not germinate, or its pollen tube will be inhibited from reaching the ovary.

Flower Types

Although there are male and female parts of the plant there are many flower variations.

A. Self-fruitful - complete self-pollinating, i.e. some beans and olives. Parthenocarpic, i.e. Navel orange, banana, seedless persimmon, purple mangosteen.

B. Partial self-fruitful - complete flowers that set a better crop by self- or cross-pollination, i.e. passion fruit, avocado, guava, mango.

C. Full self fruit - single sex flowers. On the same plant, i.e. jakfruit, pumpkin.

On separate plants, i.e. papaw (dioecious) pili nut.

Male or female sterile hermaphrodite flowers, i.e. rambutan, casimiroa.

Although some flowers may have both functional male and female parts, the pollen may not be compatible, or pollen from other varieties may be preferred by the flower, i.e. macadamia, apples.

Some flowers have male and female parts that function at different times of the day or days apart, i.e. avocado, custard apple, tall coconut.

Many tropical fruits have a mixture of flower types on each tree, i.e. lychee, cashew, mango. It is important to know flower types and when their parts are functional to understand their pollination needs.

The parts of the flower

Methods of Pollination

For those flowers that are not self-fruitful, some agent is needed to transfer the pollen. Flowers that are fertilised by pollen from another flower are called open pollination flowers. The process is called cross-pollination and usually the seeds produced grow into plants that are slightly different to either parent.

Methods by which pollen is moved from the anther to the stigma vary considerably.

Wind, agitation and gravity are very important agents to most cereal plants and some trees, i.. e. pecan and pistachio nuts.

Insects - generally the most important method in most orchard crops. Some plants are reliant on specific insects, i.e. fig, cocoa, and custard apple, as they have flower access that is small and restricts most insects.

Other pollination agents include animals such as birds, bats and possums, water, both rain and flowing water and hand pollination.

PART III

INSECT POLLINATION

Virgin forest areas usually have a large population of flower-visiting insects including native bees and feral bees (honey bees gone bush). As the scrub is cleared, these insects are reduced. The larger the clearing the greater the reduction of insects.

Most fruit trees flower for only a few weeks in the year, and when large orchards of a single fruit type finally come into flowering, there are very few insects to adequately pollinate the area of crop.

This is further complicated as various chemical sprays are used throughout the growing stage and particularly at the flowering stage. Some of these sprays are highly toxic and long-lasting. Often your beneficial insects are more easily killed than the pest species. Various flies, beetles, wasps, moths and native bees are some of the local insects that aid pollination.

To replace these, honey bees are often introduced. Although honey bees are useful to many crops, they are not suited to all crops. Some flowers are not attractive or accessible to them.

Honey Bees as Pollinators

Honey bees are very efficient pollen carriers, as pollen is the protein component of their diet. Bees collect and carry pollen to their hive with the aid of many branched hairs over their body. They are natural pollination brushes. Honey bees can be managed to have large populations of field bees at flowering times. They can be easily moved, allowing them to be shifted in and out of the orchard when necessary. In some crops, honey bees produce a surplus of honey that may be harvested. This will vary with local conditions. Lychee, macadamia, avocado, mango and citrus are crops that can produce honey.

Insect Requirements

Any plants flowering within a few kilometres, other than your target orchard crop, may compete for the available insects. Over a period of years you will be able to assess your insect population by observing and recording insect activity on your crop. Do this at various times throughout the day and night - particularly on fine days. Comments on the amount of flowering, rainfall, extremes of temperature, pest and disease levels, changes in crop management and harvest figures will aid in the determining of pollination needs. In the meantime, general figures are available for some crops. There are some examples following:

| CROP | NO. OF BEES PER 1000 FLOWERS |

| Apple | 1 |

| Cucumber | 10 |

| Kiwi Fruit | 6 |

| Seed Lucerne | 3 to 6 per m2 |

| Rockmelon | 100 |

| Oil Seed Sunflower | 250 |

| Watermelon | 10 |

Various crops have recommendations of numbers of hives per area of crop. These are general recommendations that vary with the population of local insects and poor weather.

| CROP | NO. OF HIVES PER 10 HA |

| Apple | 20 - 40 |

| Avocado | 20 - 40 |

| Citrus | 10 - 20 |

| Cucumber | 10 - 20 |

| Grapes | 2 |

| Kiwi Fruit | 40 - 80 |

| Lucerne - Seed | 40 - 80 |

| Macadamia | 25 - 60 |

| Pumpkin | 20 - 40 |

| Rape | 20 - 60 |

| Rockmelon | 20 - 40 |

| Safflower | 20 |

| Strawberry | 4 - 40 |

| Sunflower for Hybrid seed | 20 - 40 |

| Watermelon | 4 - 20 |

PLANNING AN ORCHARD

When planning an orchard, future pollination needs should be considered.

TREE SELECTION

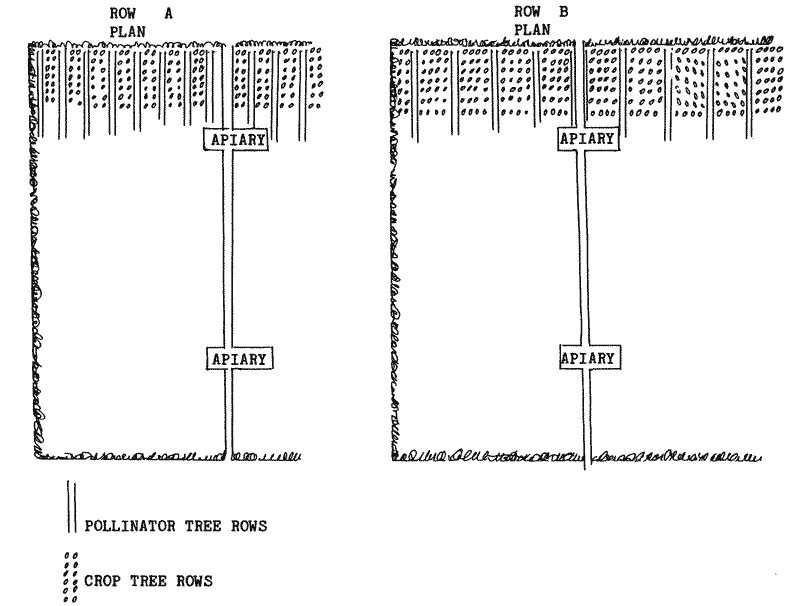

Compatible varieties and tree location should maximise cross pollination. Bees tend to fly along rows of trees, so the planting of rows of one variety is not as productive as interplanting pollination trees. Some trees may need branches of a pollination type grafted onto the crop tree.

WATER

Some crops require careful water management before, during and after flowering. This is to induce flowering and hold the crop, but the pollination of some crops such as custard apple and macadamia is aided by high humidity at flowering. This humidity aids pollen release and lengthens stigma receptivity.

APIARY SITE

Although bees will fly many kilometres, the nearer bees are to the crop, the greater the pollination efficiency. Most effective coverage is obtained by placing hives singularly, but it is more practical to have hives grouped in apiaries of 10 to 20 spaced 200 to 300 m apart.

Locate apiaries in positions protected from strong winds but where early morning sun will shine. This increases activity early in the day when some crops are more readily pollinated.

Apiary site should be accessible during wet weather and easily reached at night. Avoid locating hives where they may be a nuisance to farm workers and others. Where possible, place hives more than 100 m from gateways, tracks and buildings. In drier weather it is often necessary to provide bees with their own water supply.

ORCHARD PLANNING

CHEMICAL SPRAYS

Hives should be placed upwind of area where hazardous chemicals are likely to be used. This reduces the chance of chemical spray drift over the hives. The danger to bees should always be checked before using any chemical. It may be necessary to remove the hives from the orchard before spraying. Moving bees is usually done at night when all the foraging bees have returned. When less hazardous chemicals are used, the hives may be closed for the required period, being careful not to suffocate the hive by over-heating. In most cases it is best to apply chemicals in the early evening when foraging bees have returned to their hives.

Other benefits of spraying in the evening often include cooler working conditions, less wind causing spray drift and long chemical effectiveness.

AVAILABILITY OF BEEHIVES

Due to initial cost of setting up an apiary and the expertise and time needed to maintain it, most growers prefer to rent bee hives for the flowering period of the crop from established pollination contractors. In such cases, the beekeeper and the grower should draw up a mutually agreed contract to cover all aspects of the arrangement.

If the grower wishes to maintain his own hives, in Queensland they must be kept in accordance with the 'Apiaries Act 1982'. An outline of the responsibilities under this Act and other beekeeping information is available from the D.P.I. Beekeeping Offices listed at the end.

TIMING OF THE INTRODUCTION OF HIVES

When an apiary is moved to a new site and the bees released, they will commence to forage close to the apiary for the first few days. In time they will forage further from the apiary, especially if more attractive foraging conditions are available away from the target crop. To take advantage of this, it is recommended that 1/3 of the total hives should be introduced initially, i.e. between commencement of flowering and ¼ of crop in flower, then move the other 2/3 of the hives in when crop is near full flowering. If a particular crop has an extended flowering period, it may be beneficial to continue to move in more hives at regular periods while removing the hives that have been there the longest. If weather conditions are cold, windy or raining, particularly if the crop is unattractive to bees, it may be necessary to increase the numbers of hives for that period, as less bees will be foraging under these conditions.

Foraging bees from hives located permanently may be slow to change to a target crop when it first starts to flower.

If conditions in the area have not been good, and suitable feeding techniques have not been used to maintain colony strength, permanently sited hives will be too weak to be good pollinating units.

BEEKEEPING ADVISORY SERVICE ADDRESS

Apiculture Section,

Entomology Branch,

Department of Primary Industries

LEAFLETS ON POLLINATION AVAILABLE FROM THE D.P.I.

Honey Bees for Pollination - R. Goebel.

Pesticide Toxicity to Honey Bees - R. Rhodes and J. Barrett.

Pesticides and Honey Bees - J. Rhodes.

Managing Honey Bee Colonies for Pollination Purposes - J. Rhodes.

Australian Native Bees - R. Goebel.

| ROW PLAN A - When two crop tree varieties are used | ROW PLAN B - When one crop tree variety and one pollination tree variety are used. |

DATE: May 1987

* * * * * * * * * * * * *