SOIL AS A HABITAT FOR PLANTS

Soils are generally referred to as mineral soils,which contain 1-10% organic content, or organic soils, which contain 80-95% organic content. Peat deposits on the Atherton Tablelands are an example of organic soils Most of our soils, however, are mineral soils.

Soils have four major components: mineral materials, organic matter, water, air.

Mineral materials comprise 40-50% of volume of mineral soils and are made up of rock fragments and such minerals as quartz, clays and silts. These supply most of the elements for plant growth.

Organic matter is 1-10% by volume of mineral soils. It is responsible for the loose, easily-managed condition of soil, is almost the sole source of nitrogen, the major source of phosphorus and sulphur and the main source of energy for microorganisms which convert the organic matter to humus. It increases the water-holding capacity of soil and the percentage available to plants.

Soil water is 20-30% of volume. Its movement and availability to plants is determined by the nature of soil. The soil water dissolves salts in the mineral materials to form the soil solution and enables the plant roots to absorb these salts.

Soil air is 20-30% of volume and contains more carbon dioxide and less oxygen than the atmosphere. The amount of soil air depends on the degree of granulation of soil and the water content. Rapid changes in air content have a marked effect on plant growth and soil organisms.

The soil clay and humus is vitally important to plant growth since they control the chemical and physical properties of the soil. Their surface charges attract nutrient ions and therefore reduce their leaching. These charges help to maintain a stable granular structure. The humus colloids have a greater nutrient and water-holding capacity than the clay. However the clay colloids are usually more numerous. A good soil contains a balance of the two.

The soil solution is soil water containing dissolved ionic forms of plant nutrients. It is not always continuous and does not move freely in the soil and is very changeable in volume and concentration of nutrients. Under low rainfall and poor drainage, the salt concentrations in soil solution can increase to the point of being toxic to plants.

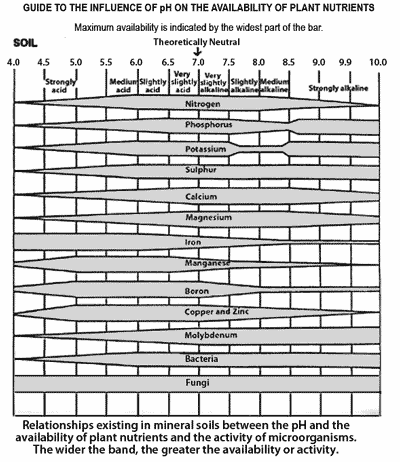

The accompanying chart from Brady shows the relative availability of plant nutrients and the activity of microorganisms at various soil pH values. From the chart it can be seen that generally a pH of 6.0-7.0 is to be preferred.

Soil organisms are essential for plant growth. Nearly all natural soil reactions are dependant on biochemical changes. They have a marked effect on physical and chemical changes in soil. The decay of plant residues by insects, earthworms, bacteria, fungi and actinomycetes releases nitrogen, phosphorus and sulphur and converts the residue into humus. The weight of organisms in a soil may vary from 5000 to 20,000 kg per hectare.

Earthworms are the most important soil macro-animal. There are over 200 species. They pass through their bodies up to 50 tonnes of dry earth per hectare per year. Their usual densities are 30-300 worms per square metre. Earthworm casts which on a cultivated field may be as much as 18,000 kg per hectare are higher in bacteria, organic matter, nitrogen, exchangeable calcium and magnesium, available phosphorus and potassium than the soil itself. They improve aeration and drainage, transport lower soil to the surface, mix and granulate the soil by dragging it into their burrows, undecomposed organic material.

Generally the conditions favourable for earthworms are also suitable for the growth of other soil organisms. These are a moist soil, reasonable aeration, organic material to feed on, a pH greater than 5.5, a soil temperature about 10ce. Earthworms can operate to depths of two metres.

Bacteria, which are one of the most important soil microorganisms, are responsible for nitrification, sulphur oxidation and nitrogen fixation.

Farming practices generally have a detrimental effect on the soil. Cultivation tends to reduce the total pore space and the size of pore spaces and therefore increases the proportion of micro-pores. The organic content is reduced through oxidation. The stable aggregates are broken down and the soil is compacted.

There are two main soil types on the coast in the Cairns region. The dominant type is a dark red-brown, relatively-deep, acid clay loam, strongly-structured, friable and permeable. Uncleared land is moderately fertile with a well-developed, undecomposed, leaf litter on the surface. Fertility declines rapidly when cleared and deficiencies in nitrogen, phosphorus and molybdenum may occur. The subsoil has a pH of 4.0-4.5. The second soil type is a yellow-brown, deep, friable soil when moist, but firm when dry.

The growth of plants is controlled by light, mechanical support, heat, air, water and nutrients. The rate of plant growth will be controlled by the component which is least optimum, and in the case of nutrients, a proper balance must exist between the concentrations of soluble nutrients.

There are seventeen essential elements for plant and micro organism growth. Air and water supply carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and some nitrogen (all together about 95% of fresh plant tissue) while soil solids supply the bulk of nitrogen and all of the phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium and sulphur, (the six primary elements) plus the trace elements, iron, manganese, boron, molybdenum, copper, zinc, chlorine and cobalt. Other trace elements such as silicon, vanadium and sodium are helpful for the growth of some species of plants, while iodine, fluorine, chromium, lithium and selenium are essential for animal and human growth. Low levels of trace elements generally exist in sandy, organic or very alkaline soils. Uncultivated soils contain higher concentrations of trace elements in surface soil due to the natural organic mulch. Basaltic soils (from igneous rocks) contain all the trace elements.

The levels of primary elements in surface soils are generally as follows:

Organic matter - 4000-100,000 ppm. Usually critically low.

Nitrogen - 200-5000 ppm. Usually in small amounts. Mostly unavailable to plants. Virtually all from organic material.

Phosphorus - 100-2000 ppm. Usually in small amounts. Mostly unavailable to plants, largely from organic material.

Potassium - 1700-33,000 ppm. Plentiful in most soils except sands, but often not available. Mostly inorganic forms, about 1% available.

Calcium - 700-36,000 ppm. Usually less than potassium, and when lacking, soils tend to be acid. Readily leached. Mostly inorganic forms. About 25% available.

Magnesium - 1200-15,000 ppm. Deficiencies often a problem. Mostly inorganic forms. About 6% available.

Sulphur - 100-2000 ppm. Usually no more than phosphorus, but more readily available. Not usually critical. Largely from organic material.

The soil pH affects the availability of essential nutrients and the solubility of certain elements that are toxic to plants. In humid regions, the soil pH is usually 4.5-7.5 while in arid regions it is 6.5-9.0.

They are moderately to highly permeable acid to neutral soils with moderate fertility in their natural state. When cleared, deficiencies in nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium may occur.

West of Cairns on the Atherton Tableland, red basaltic soils dominate. These soils may be up to seven metres thick, are strongly structured and very friable. Drainage is very free and pH is acid to very acid towards the subsoil. In their natural state, these soils are very fertile but with intensive farming, deficiencies in nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur, molybdenum and potassium may occur.

Soils in the Mareeba-Julatten area are yellow-grey loamy sands or sandy clay of low organic content. They are sometimes subject to severe waterlogging. Surface soil is mildly acid to neutral. Subsoil often has high salt content. Fertility is low to very low with severe deficiencies in nitrogen, phosphorus, and calcium and deficiencies in potassium, molybdenum, sulphur, copper and zinc may occur.

References:

The Nature and Properties of Soils by N.C. Brady.

How to Get Well by Paavo Airola.

A Description of Australian Soils by C.S.I.R.O.

DATE: March 1981

* * * * * * * * * * * * *