SOIL TYPES

What is soil? This brownie coloured stuff that covers a large proportion of our land? The stuff we grow our crops in and cultivate small parcels of it in our gardens?

Our garden soil is made up of five main ingredients, mineral particles, organic matter, living organisms, air and water. The largest part is weathered rock (the mineral particles), followed by air and water, then a very small amount of the organic matter and the living organisms. The proportion of these ingredients varies considerably, not only from area to area, but in the same patch of soil. For example your soil's air to water ratio depends on when it was last watered, the soil under your compost heap has a higher ratio of organic matter and living organisms than elsewhere in your garden. I'm not going to go into the technicalities of soil chemistry and engineering but I would like to explain to you a few simple ways of finding out what sort of soil you have.

Firstly, dig up a spadeful of soil. Look, smell and feel it.

| Look: | Is there mulch on the surface? Is the soil moist or dry? What colour is it, is it all the same colour? Are there different layers? Are there bits of roots in it? Can you see any earthworms? |

| Smell: | Does it smell pleasant and "earthy" or "sour"? |

| Feel: | Give it a poke, does it fall apart readily or stick together? Okay, now pick up a small handful, squeeze it then open your hand - has it become a solid lump or a pile of small crumbs? Rub it in between both hands- does it feel gritty? Can you hear the sand particles rubbing together or is it smooth, sticky clay? |

I hope you all are lucky enough to have a soil that is somewhere in between a barren sand and a heavy clay. In order to find out try the following methods:

The Feel Method

Place a small amount of soil in the palm of one hand and moistened with water until it can be kneaded. Squeeze hard to see if a ball can be formed, then roll into a sausage shape.

Results:

Gritty, cannot form a ball, grains stick to fingers = sand

Gritty, forms a ball that falls apart easily, can be moulded into a short sausage = sandy-loam

Not gritty, not sticky, forms a spongy ball, can be rolled into a sausage = loam

Not gritty, sticky, forms a spongy ball, can be rolled into a long sausage = clay-loam.

Not gritty, smooth and sticky, forms a solid ball, can be rolled into a long, thin sausage without breaking = heavy-clay

The Water Jar Method

Put three heaped tablespoons of soil into a screw top glass jar with a few drops of washing up liquid and sufficient distilled water to mix to a slurry. When all the crumbs are broken into the slurry, add more distilled water to three-quarters of the way up the jar. Shake the jar for approximately three minutes, and then leave to stand for a week.

Over the seven days the soil will settle out into layers of clay, silt, fine sand and coarser sand at the bottom. The water may clear (sand) or hold a clay suspension.

Measure the levels:

Total height = mm

Clay height = mm

Silt height = mm

Sand height = mm

Work out percentages:

Clay height + total ht x 100 = % clay

Silt height + total ht x 100 = % silt

Sand height + total ht x 100 = % sand

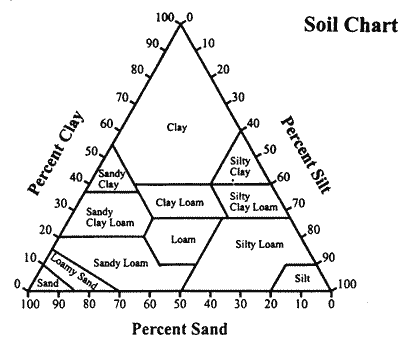

Turn to the soil chart and mark the percentage silt on the silt side of the triangle, draw a line from this point inwards parallel to the clay side. Mark the percentage clay on the appropriate side and draw a line inwards parallel to the sand side. The lines cross in the section of your solid type.

The pH of your soil

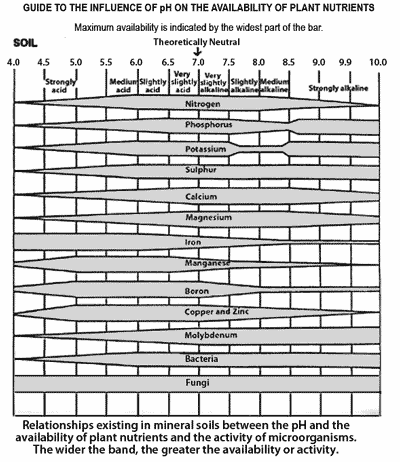

The alkalinity or acidity of the soil is its pH value. Measurements are from 0-14 with less than 7 being acid, 7 being neutral and- more than 7 being alkaline. Most plants grow within the range of 4.5 to 8.0. Earthworms prefer a range of 6.5 to 7.0 and this is regarded as the most suitable pH range for flower and vegetable beds.

Some plant species have specific pH requirements to thrive and look their best. For example, azaleas and camellias are acid soil lovers (4.5 - 5.5 pH), whilst melons and spinach prefer an alkaline soil (7.0 - 8.0 pH), then there's the hydrangeas that flower pink in alkaline soils and blue in acid soils. Most Australian native plants require slightly acid soils. It is very easy to use a soil testing kit and find out what the pH of your soil is, and they are readily available most garden centres. A pH meter, an electronic electrode with a digital readout, can also be used to measure your soil's pH, but these are much more expensive and mainly used by landscapers and nurserymen.

The Colourimetric Method

Put about 20 g (a tablespoon) of soil, from a garden trowel depth, on the card provided in the kit. Mix the liquid indicator, just a few drops, with the soil.

• Dust the soil with the white powder (barium sulphate).

• Check the colour against the pH chart.

• Repeat at several locations around the garden.

The addition of limestone or dolomite to your soil will raise the pH level. The correct rate of application will depend on soil type.

Why do we need to know about our soils?

So we can understand a little more about caring for both our plants and the media they grow in. Most of our herbs' roots are in the top 20cm of soil - the topsoil - the most precious soil - that holds all the nutrients. Some of us may only have a few scant centimetres of topsoil, others up to 60cm in depth. If we know our soil's type and pH we can take steps to improve its structure and maintain its fertility.

Gypsum acts as a soil conditioner. It improves structure in both clays and sands. Gypsum, calcium sulphate, is slightly soluble in water. The water (from rain or sprinkler) carries the dissolved gypsum into the soil, this immediately helps aggregate formation. Also, the calcium ions exchange places with sodium ions in the top soil, leaving more calcium and less sodium ions. This means the soil particles can group together into aggregates more easily. Eventually the sodium ions will be flushed down into the subsoil.

May, the beginning of the Dry and the end of the growing season for many plants, is an excellent time to spread gypsum everywhere - especially over the lawn - and even over potted plants. Use 0.5 to 1 kg per square metre. A 30 litre bag of gypsum was ample for my quarter acre garden, with a little left over for use in potting mixes. The use of fertilizers (blood and bone/slow release/etc) applied little and often, improves soil nutrient levels and fertility. It is good to follow up with a soil wetting agent, especially applied around the base of favourite specimens, then mulch well.

Organic matter improves soil structure and also provides plant nutrients. A good layer of mulch also reduces the soil evaporation rate, reduces soil erosion and suppresses weed growth. A composted mulch breaks down and 'disappears' into the soil. Your garden beds will need mulching at least once a year. Start a compost heap down the bottom of the garden. Pile up grass clippings, twigs, leaves, potato peelings and other kitchen green waste, coffee grouts and tea bags - throw in a few comfrey leaves, turn the heap once in a while with a garden fork - Hey Presto- beautiful mulch.

Why is pH important?

Because outside the 5.5 to 7.5 range the availability of nutrients and elements in the soil· alters and plants suffer from various toxicities and/or deficiencies. For example in medium alkaline soils (pH 8.0 to 8.5) most plants are unable to take up phosphorus and the trace elements manganese, iron, boron, copper and zinc - and show it in their leaves (yellowing). At the other end of the scale, in highly acid soils (pH 4.0 to 5.0) nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, sulphur and the trace element molybdenum become unavailable. Refer to the "Availability of Plant Nutrients in Soil" chart for further details.

The pH of your soil can be raised (by digging in builder's lime) or lowered (by digging in sulphur) - but it can be quite expensive, and not a permanent fix. It is better to do a little research (try the Society's marvellous library) and grow what is suited to your soil type and pH. It is surprising how soon results are noticed by improving the structure of your garden soil. Healthy, well-fed plants are better able to cope in times of stress (like being deluged by rain and floods) and are more resistant to insect attack and disease.

Armed with the soil type and pH level of your garden soil you can check your Garden Guide book to see which plants are most suitable to grow successfully at your place.

Happy gardening - and start spreading that mulch!

References:

K Handreck: Gardening Down-Under

CSIRO: When Should I Water?

Handreck and Black: Growing Media for Ornamental Plants And Turf

E Romain and S Hawkey: Herbal Remedies in Pots

Brenda Little: The Illustrated Herbal Encyclopedia

DATE: November 2000

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *