UNDERSTANDING TREE ANATOMY FOR IMPROVED PLANT GROWTH

The difficulties in understanding tree anatomy have become increasingly compounded over the years by what were once assumptions later being taken as fact. A real understanding of tree anatomy and growth may now require a complete rethinking of what we have learned and since believed to be true.

At least that is a conclusion which may be drawn from recent research, published in the Canadian Journal of Botany 'How Tree Branches are Attached to Trunks', which shows how fundamental some of these assumptions can be. The research was conducted by Dr. Alex Shiga, who presented it to Australian horticulturists on a lecture tour sponsored by Rivett Enterprises earlier this year.

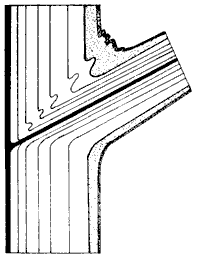

Established thinking on the arrangement of woody tissues in trees suggested they were continuous between the branch and trunk. While this is undoubtedly true, it may not come about in the way many imagine. The left hand diagram shows the presumed arrangement of tissues given in most textbooks, while the right hand one summarises Dr. Shiga's recent findings. This picture was developed from a range of dissections and other studies, made over successive periods throughout the growth cycle.

|  |

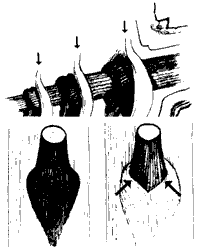

He discovered that branch tissues develop first, beginning early in the season and maturing from the tip towards the base. At the junction with the trunk, they turn abruptly downwards, forming a shield-shaped collar. Later in the season, the trunk wood develops and forms a second collar around the branch and over the first one. Thus, the union of branch and trunk grows and is strengthened, by a series of overlapping collars.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TREE CARE

If the upper tissues of the branch were continuous with the trunk wood above it (left hand diagram), upward movement of water and solutes from the roots would have only two possible ways of passing a branch. Such movement would either rely on sideways movement between individual vessels or would need to move along the lower tissues of the branch and return along the upper tissues before continuing up the trunk. There is no evidence to suggest that the second process occurs at all and Dr. Shiga's previous work on decay compartmentalisation suggests that the first would at least be very limited.

However, the organisation of tissues shown on the right suggests that no connection between the branch wood and that of the trunk above it exists and that upward movement of water and solutes (other than that destined for the branch itself) is not impeded or diverted by the branch connection.

However, the organisation of tissues shown on the right suggests that no connection between the branch wood and that of the trunk above it exists and that upward movement of water and solutes (other than that destined for the branch itself) is not impeded or diverted by the branch connections.

This helps explain why decay, progressing into the trunk from a branch wound, does not seem to affect wood above the branch. On the other hand, an injury or pruning cut which damages the collars will lead to decay above (as well as below) the branch by direct exposure of these tissues.

It is also easy to see, from this picture of the branch connection that the weakest point will be in the angle of the crotch. This may support the belief that a weaker branch connection occurs with a more acute crotch angle, but from this current research it is not clear exactly how this is so.

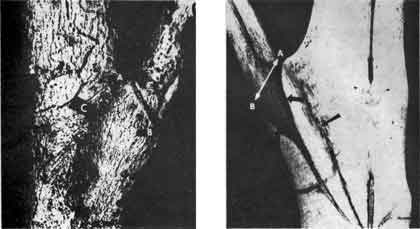

Above: branch connections on a Red Maple. Here the branch has died, but the collars are undamaged. Inside the tree (Right) decay progresses towards the centre of the trunk but is restricted by the branch collars. The surrounding tissues remain healthy and unaffected. The line A-B shows where the branch may be safely cut away. Cutting closer to the trunk would damage the collars and cause extensive decay of the trunk wood.

FOR GROWTH

The timing of growth is also important. If the strength of branch connections is dependant upon the formation of an interlocking series of collars then management practices which encourage their formation may produce a stronger, healthier tree. In an interview with Australian Horticulture, Alex Shiga suggested that in some ways we may be caring for trees too much, particularly in nurseries. "We place too much emphasis on stem growth and girth," he said. "Fertilizer is not simply good. We should look for ways of encouraging the right kind of growth at the right time, rather than just producing more plants, faster," Dr. Shiga explained. This is particularly important for growers of advanced plants as Dr. Shiga believes they may be producing trees that will become weak and dangerous in years to come. He also said that differences in growth timing between stock and scion may be an important factor influencing the long term compatibility of some graft unions.

Alex Shiga has been a tireless researcher for many years and has published numerous papers on a wide variety of tree-related topics. He now sees his role as more of an educator than a researcher and it may be hoped that other lecture tours, like the one he completed in March this year, will follow in the future. On this trip, he spoke on many subjects including the timing of certain tree work practices, programmed maintenance, branch attachment, the good and bad of fertilisers and how compartmentalisation of extensive decay can lead to the 'starvation' of a tree.

DATE: November 1986

* * * * * * * * * * * * *