THE BOTANY AND CULTIVATION OF THE CASHEW

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Anacardium occidentale

FAMILY: Anacardiaceae

Cashew trees grow in a wide range of climates between the latitudes of around 25 ° north or south of the equator. Close to the equator, the trees grow at altitudes up to about 1500 m, but the maximum elevation decreases to sea level at higher latitudes. Although cashews can withstand high temperatures, a monthly average of 27°C is considered optimum. Young trees in particular are very susceptible to frost, and cool spring conditions tend to delay flowering.

Annual precipitation may be as low as 1000 mm, provided by rain or irrigation, but 1500 to 2000 mm is considered optimum. Established cashew trees in deep soil have a well-developed, deep root system, allowing trees to adapt to long dry seasons. Well-distributed rainfall tends to produce constant flowering, but a well-defined dry season induces a single flush of flowering, early in the dry season. Similarly, two dry seasons induce two flowering flushes.

Ideally, there should be no rain from the onset of flowering until after harvesting is completed. Rain during flowering results in the development of the fungus disease anthracnose, which causes flower drop. As the nut and apple are developing, rain causes rots and severe crop losses. Rain during the harvesting period when the nuts are on the ground causes them to deteriorate rapidly. Sprouting occurs after about 4 days of damp conditions.

SOILS

Cashews tolerate a wide range of soil types, but the best growth and production occur in deep, well-drained sands or loams. In deep friable soils, full development of the extensive lateral root system occurs, and the deep taproot system reaches several metres in length and can sustain the tree through long dry seasons. Deep sands, sandy loams, gravelly soils and red latosols have been found to be physically ideal, although the lighter soils require special care with nutrition. Cashews cannot tolerate poor drainage.

Shallow soils give rise to a poorly-developed root system with consequent low drought tolerance and unthrifty top growth. Such trees are easily blown over during the wet season.

VARIETIES

As self-pollination and open pollination both play a part in cashew seed production, seedlings tend to be highly variable, and no true-to-type varieties are reproduced from seed. However, in some overseas producing districts, generations of growers have selected seed lines that reproduce some characteristics reliably. Many of these lines have been given varietal names.

Selected trees may be reproduced by vegetative propagation methods such as budding or grafting onto seedlings, layering or cuttings.

Characteristics to select for include vigorous growth and good, early fruit set. The nuts (kernel and shell) should weigh 8 to 9 g, with a minimum of 6 g, and have a specific gravity of at least 1.0. Apple colour ranges from bright red to bright yellow. Selections from the yellow to fawn range have been found to have the best resistance to anthracnose and to be associated with the best yield performance.

FLOWERING AND FRUITING

Flowering normally occurs following the growth flush at the end of the wet season, but its timing and duration are strongly influenced by temperature. Flowers are produced at the end of the new shoots. Thus flowers and fruit are borne on the outer extremity of the canopy.

Both male and bisexual flowers are produced, with male flowers predominating for the first month. Pollination is mostly by insects. The flowering season varies in response to the weather and the variety, but it usually extends over 3 to 4 months.

After pollination, the fruit takes 6 to 8 weeks to develop. The nut develops first and the apple fills out during the last fortnight before nut drop occurs. Nut drop continues for 6 to 8 weeks.

In Cairns, the earliest varieties begin flowering in late August and early September and nut drop begins in mid-October. Nut drop continues until mid-January from the latest varieties. The corresponding stages in Cape York Peninsula are about a month earlier because of the warmer temperatures.

Cashew Culture

Until recently, little serious thought has been given to establishing a cashew industry in Australia. Consequently, no research has been directed to the study of the crop, although small plantings have been studied on research stations sited in localities suited to wet tropical crops, but not suited to cashews.

The following comments have been distilled from overseas literature, with suggested cultural methods that should be effective in Queensland.

PROPAGATION FROM SEED

Trees propagated from seed may be grown on to produce the crop, but there will be considerable variability between the trees. Preferably, seedlings should be grown as stocks to be budded or grafted with material from superior trees.

Only sound seed from selected trees should be used to produce seedlings. Further selection is for seed with high specific gravity to ensure a high rate of germination. To select seed with a specific gravity of 1.0 or higher, place the seed in water and discard the floaters. For higher specific gravity and thus higher germination, float off undesirable seeds in a solution of 150 g sugar per litre of water.

Fresh, dried seed should be sown, as the viability tends to decline with age. For field planting, two or three seeds are sown 25 mm deep at each site, and covered with straw mulch. After the seedlings have struck, the weaker ones are cut off at ground level and the strongest seedling is retained.

Alternatively, seedlings may be established in deep planter bags in a nursery. Deep bags are necessary because cashew seedlings rapidly develop a very strong and deep taproot system. Plant one seed in each bag and cover it with 25 mm of potting medium. The seed should germinate within 1 to 3 weeks. The seedlings should be planted out from the bags within 3 to 4 months, otherwise the taproot system is cramped and the planted trees are prone to blow down during wet, windy weather.

VEGETATIVE PROPAGATION

Vegetative propagation of superior trees gives the grower the opportunity to establish desirable clones. Labour costs involved in vegetative propagation are high, but are amply rewarded if effective methods are used. However, considerable research is still required to perfect vegetative propagation techniques.

Air layering (marcotting) produces vigorous young trees, but only a limited number can be taken each year without seriously affecting the parent tree.

Overseas research has found that difficulties occur with vegetative propagation by cuttings, and there is a need for further research. Reasonable results have been obtained from 20- to 30-cm-long cuttings taken from lateral shoots after a growth flush. The cuttings are trimmed to one leaf, dipped in a rooting hormone and three-quarters buried at an angle in an open-textured planting medium. The cuttings are grown in filtered light in a high humidity.

Many methods of budding are used, but the most common is the patch bud, using patches of about 2 cm square cut from current season's shoots. The seedling is budded at a height of 20 to 40 cm above the ground and the stock is cut off about 20 cm above the patch. About 2 weeks later, when the bud has taken, the scion is cut back to just above the bud. Seedlings may be budded when they are 6 to 12 months old. For best results, the scion from which the bud is taken should be the same thickness as the stock. Autumn appears to be the best time for budding in Queensland.

Many grafting methods are used successfully, but cleft grafting is probably the simplest. Best success has been obtained when the seedling stocks are 3 to 4 months old. Autumn appears to be the best time for grafting in Queensland.

Good scion wood for budding or grafting may be difficult to obtain, as growth on mature trees is often thin and gnarled, and the buds are generally close together. Trees selected for scion wood should be heavily pruned, well-fertilised and watered to produce vigorous, straight scion sticks and plump buds. This requires a lead time of 2 to 3 years.

SPACING

The trees are long-lived and spreading, and wide spacings are required. A suggested spacing is 12 x 12 m, giving 70 trees/ha. A closer spacing of 12 x 6 m (140 trees/ha) could be used to maximise early production, but the planting would need thinning to 12 x 12 m as the canopies come together.

FERTILISING

Optimum fertilising would depend on the soil, the climate, and the stage of growth of the crop, but no investigations have been carried out in Queensland. A mango-fertilising schedule could be used as a guide, as the growth and bearing pattern of mangos is similar to that of cashews. However, the economic value of the schedule is not known.

Fertiliser should be applied just before rain or irrigation. This is especially important for urea, which volatilises rapidly if it is not washed into the soil.

While the trees are small, applications should be made under the canopy. As the trees age and the canopies come together, fertiliser is applied in strips in both directions between the rows.

IRRIGATION

Irrigation is necessary to establish the trees, and experience at Bamaga in North Queensland showed that irrigation during the dry season doubled the growth rate of young trees. Small under-tree sprinklers are ideal until the trees are 4 years old.

Because of their deep taproot system, established cashew trees can survive the dry season without irrigation, but premature nut drop is a common problem. While not essential, irrigation could prove to be a major benefit to production, largely by preventing nut drop. However, the economics of irrigation are unknown. For mature trees, application of about 1800 l/tree each fortnight during the dry season would be required. The irrigation system must be placed in a way that does not interfere with harvesting or weed control operations.

PRUNING

After the trees reach about 2 years old, the lower branches are pruned off flush with the main trunk. Pruning is continued to train the tree gradually to develop a skirt high enough to allow access to harvesting machinery after the third year. No other pruning should be necessary.

The main leader should be carefully protected from damage by animals or insects. Loss of the leader induces the development of vigorous sideshoots from the lower trunk for up to 2 years, substantially increasing the labour requirement for pruning and training.

WEED CONTROL

Mowing between the rows encourages the development of low grass growth to protect the soil from erosion. While the plants are young, ring weed around them for about 1 m, by chipping or with a surface mulch. Keep the mulch well clear of the trunks. Paraquat has been used successfully to control weeds, but the cashew leaves and green stems should be fully protected from spray drift. New herbicides under test may allow easier weed management in the future.

During harvesting, the nuts are collected from the ground under the trees. Therefore, growth should be mown and raked away from under and around the trees before nut fall begins.

HARVESTING

As the nuts mature, they fall to the ground from where they are collected. Because of the protracted maturity time, picking from the tree or shaking the trees to hasten the drop is not considered a viable proposition.

If the apples are to be used commercially, hand-picking from the tree is necessary. The extra labour costs make viable commercial use of the apples unlikely. Once they fall to the ground, the apples dry out within 5 to 7 days during sunny weather. However, because they are falling constantly, there are always wet apples to be disposed of during the harvest. Nuts are swept from under the trees into windrows for collection.

Mechanical harvesters are available which sweep and pick up the nuts in the one operation. Unless it rains, two to four collections are needed during the harvesting season. To prevent the nuts from rotting, irrigation is discontinued between the beginning of nut drop and completion of harvesting. If it rains during the harvesting season, nuts must be collected every 4 to 7 days.

YIELDS

Reports from overseas quote a range of tree yields between nil and 100 kg. Yields of seedling trees vary widely. Other factors responsible for yield variations include:

• age and vigour of the tree;

• number of bisexual flowers produced;

• effectiveness of pollination;

• nut weight;

• pest and disease incidence; and

• the extent of premature nut drop.

Therefore, site selection, tree selection and effective plantation management are necessary steps towards maximising yields.

In North Queensland, yields of 30 to 40 kg/tree seem attainable, but the economics of this level of production appear doubtful.

There is a tendency for alternate bearing in cashew trees, which is most marked in older trees and in those that produce large nuts. Thus, long term yield recording is necessary before selecting trees to provide vegetative planting material.

MARKETING

As a cashew industry has not yet been established in Australia, a marketing procedure has not been developed. Probably, the harvested nuts would be air-dried on the plantation and possibly stored, before being forwarded to the processing factory, where they would be graded.

PESTS AND DISEASES

Reports in overseas literature mention a wide range of pests and diseases that attack all parts of cashew trees. As there is no commercial industry in Australia, formal studies have not yet been carried out. Observations have been made on small plantings throughout Cape York Peninsula, as well as on the Kamerunga Horticultural Research Station near Cairns, where the climate is too wet for commercial cashew production. But the findings offer some guide to a few of the problems that may be encountered in potential commercial growing areas.

In the wet climate near Cairns, damage has been caused by a mirid bug (Helopeltis sp), the banana spotting bug (Amblypelta lutescens) and the disease anthracnose caused by the fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. However, their incidence would probably be minor in a drier climate more suited to cashew production. Red-banded thrips (Selenothrips rubrocinctus) have caused serious leaf drop in some years and attack would probably be more severe in a drier climate. Leaf drop caused by thrip attack or strong winds retards the trees for up to 2 years until full leaf colour is re-established. Every effort should be made to prevent leaf loss.

Termites may cause problems in recommended cropping areas, although cashew wood is said to be resistant to their attack.

PROCESSING

The processing of cashew apples must be carried out close to the production centre, otherwise they spoil in transit. Processed cashew apple products include juice, syrup, wine, canned fruit, chutney, alcohol and vinegar.

Modern commercial processing of cashew nuts is designed to recover the maximum percentage of whole kernels and the maximum percentage of cashew nut shell liquid (C.N.S.L.). Shelling cashews to obtain the kernels is very difficult because of:

• The irregular shape of the nut;

• The tough leathery nature of the shells; and

• the caustic nature of C.N.S.L.

In most commercial processes, the whole nuts are roasted in a bath of C. N. S. L. to extract the C.N.S.L. from the shells. Further extraction may be obtained by centrifuging. Several different mechanical methods are available for removing the shells, but all methods produce a proportion of broken kernels. After shelling, the kernels are peeled to remove the testa, graded according to international specifications and packed for market in airtight containers.

SMALL SCALE ROASTING

A primitive method is available for roasting very small quantities of nuts. However, the method is not recommended, as large volumes of acrid C.N.S.L. fumes are driven off when the nuts are heated.

Using the method, the whole nuts are placed in a shallow pan such as a frying pan with large holes drilled in the base. The pan is placed over an open fire. As the shells begin to burn, C.N.S.L. drips through the holes and catches fire, giving off choking fumes. The nuts are stirred to ensure even roasting. Timing is a matter of experience, but it is very important to avoid burning the kernels. After a few minutes, water is sprinkled over the burning nuts to extinguish them and they are thrown out to cool. The nuts are then shelled very carefully with rubber gloves to avoid injury from remaining C.N.S.L. The kernels and shells must be kept separate to avoid contamination of the kernels with C.N.S.L.

BOTANY

The cashew, Anacardium occidentale, Family Anacardiaceae, is native to tropical America from Mexico to Peru and Brazil, and also to the West Indies. It is related to the mango, the pistachio nut and also to the Australian native rainforest trees, the Burdekin plum and the tar tree, cedar plum or native cashew. Although cashews have become naturalised in parts of Cape York Peninsula and in beach sand areas at Forest Beach near Ingham, the crop has not yet been grown commercially in Australia.

The cashew tree may be tall and slender, but is ideally a symmetrical, spreading, umbrella-shaped tree. It is an evergreen perennial growing as tall as 15 m. However, trees growing under harsh conditions tend to have distorted branches, failing to develop the ideal shape. The tree has dense foliage and develops an extensive lateral root system and a taproot that is capable of penetrating to a depth of several metres.

Tree growth is very rapid over the first 5 to 6 years and the first crop may be set as early as the second year. Most trees bear by the third year. Although the trees live longer under ideal conditions, it is generally considered that the economic life of a planting is 30 to 40 years.

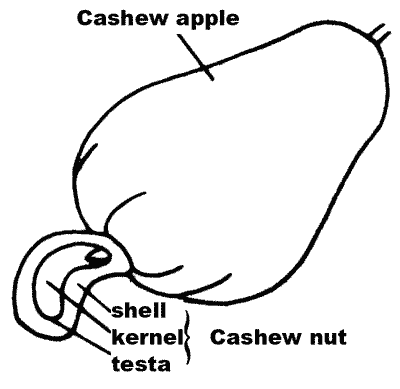

The fruit is the kidney-shaped nut or seed which is suspended below the juicy cashew apple. The apple is a swollen pedicel. See Figure 1.

USES

The edible kernel is the highly-prized cashew nut of commerce, which is usually sold as roasted cashews. Small or broken nuts may be used in confectionery or made into cashew butter, which is similar to peanut butter. A high-quality, pale-yellow, sweet oil may be extracted from the kernels.

The commercially valuable cashew nut shell liquid (C.N.S.L.) is extracted from the shell and is used as a waterproofing agent and as a preservative. When distilled and polymerised, C.N.S.L. is used in insulating varnishes, lacquers, inks, brake linings, and in acid- and alkali-resistant cement and tiles. The testa surrounding the kernel contains 25% tannin.

The apple is edible but often astringent. It may be used in jam, jelly, syrup or fermented for wine. The filtered juice is marketed in some countries. However, the economic value of the processed apple is often poorly-rated and it is usually discarded.

Table 1. Suggested fertiliser schedule for cashews (g/tree)

| Year | January (Urea) | February (10:2:17) |

| 1 | 50 | 150 |

| 2 | 80 | 200 |

| 3 | 100 | 300 |

| 4 | 150 | 500 |

| 5 | 200 | 700 |

| 6 | 300 | 1000 |

| 7 | 300 | 1000 |

| 8 | 400 | 1500 |

| 9 | 400 | 1500 |

| 10 | 500 | 2000 |

| 10+ | 500 | 2000 |

DATE: May 1987

* * * * * * * * * * * * *