FRUITING BEHAVIOUR OF DURIAN CLONES IN THE MARDI COLLECTION

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Durio zibethinus

FAMILY: Bombacaceae

In general, there is lack of information on yield and stability of performance, even amongst recommended durian varieties in the country. Local durian cultivation in the meantime, suffers from various production problems including that of availability of supply due primarily to the seasonality of fruiting. A study over eight seasons on the fruiting behaviour of 42 durian clones revealed sufficient genetic variation which, if wisely exploited, should effectively reduce some of these problems.

There is scope in increasing both the number of seasons and the length of fruiting seasons so as to extend the availability of supply of the durian fruits. Through such efforts, both growers and consumers can enjoy the benefits of a more regular supply of fruits, as well as greater stability in durian price. A clonal mixture incorporating aspects of biannual bearing and judicious use of early, medium and late season clones are suggested for increasing and extending productivity in durian orchards.

INTRODUCTION

The durian, Durio zibethinus Murr. is considered the most popular fruit in West Malaysia, where the crop is estimated to occupy no less than 18.5% of the area under fruits (ANON, 1984). Despite its socio-economic importance, the current scenario of local durian cultivation is still beset with many problems, especially that related to season and seasonality of production. Whilst it must be admitted that there exists a large number of high quality durian clones in a country, the performance of these varieties is scarcely reported. This is especially true in terms of yield performance over time and environment. Lack of such reports could be attributed to the long time required to accomplish such investigations.

So far, more than 80 durian clones have been registered in the country since the early 'thirties (ANON, 1980). From this list, a handful were recommended for general planting based on fruit quality alone. Yield performance and stability are either assumed or based on limited evaluation. Nevertheless, many of these recommendations, though from pre-war era, had continued to be important today e.g. D24, D2, D10 etc.

The MARDI durian collection in Serdang was initiated in 1972 and consisted, at the onset, of a duplication of the clonal materials of the Department of Agriculture. Later, more additions were made to the collection from various local and introduced sources. Clonal characterization and evaluation constitute an important aspect of work in the collection. It is aimed at understanding the extent of variability for future manipulation in crop improvement as well as providing information for selection of promising materials.

The present paper reports the results of an eight-season study on the fruiting behaviour of 42 clones in the MARDI durian collection. It describes the extent of genetic variation in fruiting characteristics of the population over eight seasons. The paper also discusses how such variability could be successfully exploited to increase fruit availability by increasing the number of seasons as well as extending the period of each season. Some socio-economic implications of these findings are also highlighted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The set of 42 durian clones in the MARDI durian collection were established in November 1972. At initial establishment, each clone was represented by six plants grown in a single row at 9.1m spacing. However, due to differential mortality, the 42 clones are presently survived by a variable number of plants (1 to 6). All plants received no special treatments apart from routine cultural management.

Flowering was first observed in late 1979, about six years after establishment, when six clones flowered, but this did not lead to any fruit set. Flowering and fruiting occurred in 1980 but fruit yield per plant was extremely low (0 to 3 fruits). Between 1981 till 1984 seasonal records on flowering and fruiting were made.

The number of inflorescences and number of fruits on individual plants were recorded in all seasons over that period. Besides these variables, two additional data sets were taken in the following manner:

(i) Estimate of number of flowers per plant

(ii) Earliness of fruit drop within season

RESULTS

Seasons and Seasonality of Fruiting

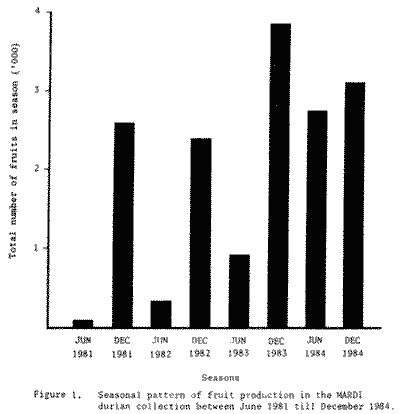

The 42 durian clones in the MARDI germplasm characteristically showed a biannual fruiting behaviour over the study period (see Figure 1). In anyone year, one season (major) appeared to be stronger than the other (the minor season). The study also revealed that in most years, the major season consistently occurred in December (as a result of the earlier August flowering) whilst the minor season coincided with the month of June (as a result of the earlier February flowering). There is thus a cyclical alternation between a major and a minor season over years.

The results further showed that the minor season fruiting appeared to be more sensitive to environmental changes. In certain years (e.g. 1981) it was so weakly expressed that fruits were mainly produced through the subsequent main season. On the other hand, fruiting in the minor season can unexpectedly become intense, as was the case in June 1984. It is interesting to note that the minor and major seasons of 1984 were in fact equally strong. Viewed in another way, it can also be interpreted that when a minor June fruiting season was enhanced, the subsequent major December fruiting season was correspondingly reduced. This implies that a fairly strong competition for available photosynthesis exists between the minor and major fruiting seasons in any one current year, as was the case in 1984.

Varietal differences over seasons

During the first five seasons, varietal differences were hardly detectable for inflorescence, flower and fruit number. Differences were, however, more pronounced and consistently so from season six onwards, when trees became more mature. This clearly implies that selection for varietal superiority in reproductive performance needs to be considered only after several seasons from initial bearing. In the present study, 1981 and 1982, may be considered unsuitable for detection of varietal differences.

Overall pattern of fruit production

An analysis of variance of fruit number per plant revealed significant differences between varieties and between seasons. It is also interesting to note variety x season was also significantly different showing that varieties did not respond in a similar way over seasons. To put it in another way, fruit yield (number) in a given variety can be high in certain seasons whilst low in other seasons. However, not all clones behaved in this general pattern. Finally, the analysis showed that, in general, plant-to-plant variation within a clone was minimal.

Correlation analysis

In general, there was no relationship for each of the three variables (inflorescence number and fruit number) between seasons except between season 5 and season 6. This shows the interaction between varieties and seasons for the three character varieties did not differ consistently between one season to the next.

In contrast, inflorescence number, flower number and fruit number were shown to be highly correlated between each other within seasons. This implies that within a season, fruit yield (number) was strongly influenced by flower and inflorescence production.

Stability of fruit yield over seasons

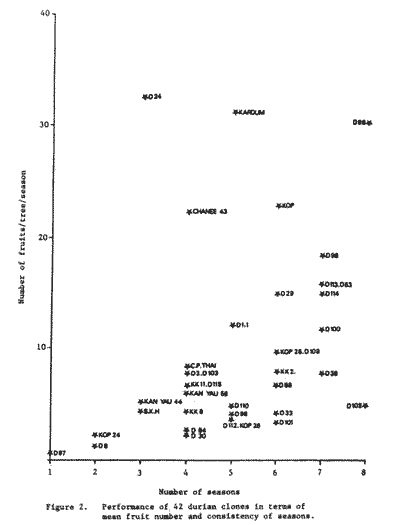

The worth of a clone should include both high yield per plant and reliability of performance over time. One way to measure stability of yield performance is by plotting mean fruit yield against the number of fruiting seasons in individual clones. Figure 2 is a summary of stability of yield performance for all the 42 durian clones in the germplasm.

The results clearly showed that D99 was most outstanding since it combined both high yield per plant and consistency in fruiting (maximum number of fruiting seasons) compared with all other clones. To a lesser extent, D98, D113, D53, D29 and D114 were relatively superior too. D24, Chanee 43 and Kardum showed average consistency in bearing but had high yield per plant. All other clones were either low yielding or not consistent in bearing or both. It is interesting to note that there exists a high number of clones showing biannual bearing habit (Figure 2).

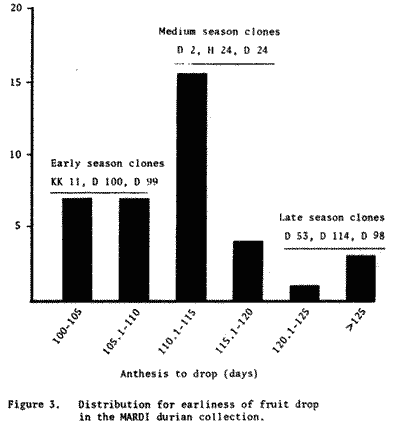

Earliness of fruit drop within season

The 42 durian clones in the germplasm showed wide variation in mean days to fruit drop from anthesis. The population as a whole was skewed in distribution with tendency towards early drop. The mean days to fruit drop was 111.2 days from anthesis with a range of 100 to 120 days (Figure 3). Based on this range, the 42 clones may be grouped into three classes in earliness of fruit drop viz., (i) early season clones - less than 110 days (ii) medium season clones - between 110 - 120 days and (iii) late season clones - more than 120 days. The wide variation implies that selection of clones at the two opposite ends of the distribution will quite effectively extend availability of fruits by at least three weeks. This has obvious economic advantages and would be discussed later. D99, D100 and KK 11 are some examples of early season clones while D53 and D114 represent clones which are from the late season group. The highly popular D24 and D2 are examples of the medium season varieties.

DISCUSSION

The wide genetic variability in seasonality and fruiting behaviour amongst durian clones presents a scope for extending the availability of fruits (Tay and Chan, 1984). Basically, this can be achieved in two ways. The first entails selection of varieties showing capability of producing two (biannual bearing) instead of just one crop (annual bearing) of fruits a year. The second would be to judiciously select and recommend a mixture of early, medium and late season varieties so as to permit maximum extension and regularity of fruit supply in each season.

Increasing the number of seasons from one to two a year constitutes a more difficult strategy since relatively few choices of varieties are available, as indicated in the study. D99 in fact, represents the only reliable candidate, as this variety combines both high fruit yield per plant and consistency in seasonal performance as a biannual bearer. It is interesting to note that biannual bearing did not significantly increase total annual fruit yield (both at the population and clonal levels) but rather allowed equal distribution of the annual yield between the two seasons. This means that biannual bearing has the advantage of redressing problems of over-production commonly faced by the local durian industry. Currently, the price of durian is severely affected by levels of production. During 'on years' where there is over-production, prices for durian usually plummet to low levels, while in 'off years', durians command exorbitant prices, outside the reach of many. To the growers, biannual bearing clones would provide more stable and reliable income, especially during the off seasons.

Extending the length of fruiting seasons through mixed planting of early, medium and late season varieties would be more appealing as there is a wider choice of entries to pick from. D100, D99 and Chanee are examples of early season varieties. At the other extreme, D98 and D114 are examples of consistently late season varieties. As for medium season varieties, the choices available are really enormous. It is interesting to note that there was a 27-day difference between early and late season varieties, and as such an extension of at least three weeks in fruiting season is thus possible.

An extension of fruiting season for durian would mean that losses can be reduced since the fruit has poor keeping quality (less than 72 hours in the average clones). To the grower, an extended fruiting season would assure a more equitable income while consumers can enjoy the benefits of a more stable durian price. Considering the two strategies together, it is logical that durian orchards should be structured on a multi-clonal mixture to fully exploit the benefits of biannual bearing and more importantly, an extended fruiting season. As a guide the following ratio of clones may be used:

| early season | D99 | 30% |

| mid season | D24 | 50% |

| late season | D98, D114 | 20% |

The above clonal mixture exploits the biannual bearing habit of D99 so that the orchard can produce some fruits in the minor seasons. In the main seasons, fruiting could be appreciably extended as D99 is an early season type whilst D98 and D114 are both late season varieties. D24, a medium season variety, would be the dominant clone. Being a high-quality fruit, fruits of D24 would suffer less drop in prices during peak production times. There are further advantages in the premium prices for D99 at the beginning of the season as well as rising prices of D98 and D114 towards the tail end of the season.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank En. Abd. Malek bin Sohot and Puan Semek bt. Deraman of the Fruit Research Division MARDI for their perseverence in data collection over the study period. Many thanks are also due to Puan Zaharah bt. Talib, Tekno-Economic Division, MARDI, for assisting in the data analysis.

REFERENCES

ANON. (1980) Registered fruit clones of the Department of Agriculture. Cawangan Pengetuaran Tanaman. Jabatan Pertanian, Serdang, Malaysia. 49 pp.

TAY, T.H. and CHAN, Y.K. (1984). A retrospect of the findings of the Techno-Economic Survey of the Malaysian fruit industry: its significance in the formulation of some research and development programmes. Malaysian Agricultural Digest 3(1), 32-48.

ANON. (1984) Program Pembangunan Industri Buah-Buahan Malaysia (1986-2000), Kementerian Pertanian Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur

DATE: November 1990

* * * * * * * * * * * * *