GROWING AND FRUITING THE LANGSAT IN FLORIDA

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Lansium domesticum

FAMILY: Meliaceae

ABSTRACT. The langsat, a member of the mahogany family, is widely planted in the Asiatic tropics for its fruit. Many horticulturists considered the tree too tropical to grow in Florida. The writer planted two langsats in the mid-fifties that ultimately fruited. Adverse winter weather can cause over 90% defoliation in bearing-size trees, followed by a rapid spring recovery. Fruiting in Florida normally occurs from August through October, though in one variety it continues on into spring. A corky bark disease on the trunk and larger limbs of mature trees is thought to be caused by a fungus canker (Cephalosporium sp.) with larvae (Tineidae sp.) feeding on the diseased tissue. The langsat requires a neutral to acid soil and a near frost-free climate, a combination seldom found in South Florida.

The langsat, a fruit of the Asiatic tropics is widely grown in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines. Yet few people are aware that under the most favorable conditions it is possible to grow and fruit this member of the Meliaceae in South Florida. Popenoe wrote "While it cannot be said to rival the Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana, L.), the langsat is considered one of the best fruits of the Malayan region." Seeds of the langsat were introduced into Florida many decades ago without apparent success, as far as establishing bearing-size trees. Popenoe stated "Experiments indicate that it is not suitable for cultivation in Florida or California, the climate of both states probably being too cold for it." Many horticulturists agreed with this noted writer and considered this fruit, along with the mangosteen and rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum, L.), both of which have now also fruited here, unsuited to even Florida's warmest areas.

In the mid-1950s, the writer set out two vegetatively-propagated five-foot langsats at his experimental fruit grove in Bal Harbour. This planting site, located between Biscayne Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, is just south of Haulover Inlet. It is an area in North Dade County that tends to be windy with some winter vegetative salt damage, but warm enough to seldom experience frost. The growing medium was a black acid sandy loam trucked in to replace an existing bay bottom marl fill unsuitably high in pH. The plants were protected in the grove from excessive sun and wind by cubical shadecloth-covered structures. These reduced sunlight by over 50%. An assumption of the grower was that the langsat in Florida would require shade-screen protection throughout its life, partly because of the low relative humidity during the winter. As the trees grew larger, taller new structures replaced existing ones. Further size increases became impracticable when the enclosures reached a 16 ft. height, with the trees inside requiring additional space. At this point, the overhead shadecloth was removed from the top of the structures. Several months later the remaining four sides of shade screen with the supporting beams were taken down without ill effects to the previously-enclosed trees. Later it was found that after the langsat reaches six to eight feet in height, shade is no longer required under this site's growing conditions. However the removal of shade should be done gradually if shock to the plant is to be avoided. Shrub-type sprinkler heads irrigated the langsats three times a week unless rain prevailed. A 6-6-6 fertilizer with minor elements was applied three times a year.

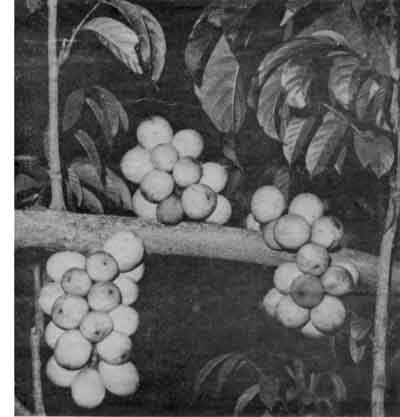

In Florida, the langsat makes a small, upright, sparsely-leafed tree with an open type growth. During the winter, adverse weather can cause over 90% leaf drop in mature trees. This is quickly replaced by new growth with the return of spring. Such defoliation is injurious to immature trees, as they can suffer severe die-back under these conditions. The pinnate leaves vary from less than a foot in length to 20 inches. These have 5 to 8 alternately-spaced leaflets 4 inches to 10 inches long by 2 inches to 5 inches wide. The numerous small, pale yellow, perfect flowers are born on racemes that protrude from the trunk and larger branches. Flowering in Florida occurs in the spring, with intermittent bloom extending on one variety into early winter. Fruit ripen in late August through October, while in the variety with prolonged flowering, from August through April. Whether or not this off-season bearing will continue remains to be seen. In Puerto Rico, Kennard and Winters report langsats in season during September and October, while Allen in Malaya states "Both langsat and duku usually bear twice a year." The fruit appear in compact grape-like clusters, are straw-colored, velvety, round to oval, up to 1¼ inches in diameter in Florida, with a thin leathery skin. Inside are five segments, varying in size, of juicy, subacid, translucent pulp with one or more seeds. Usually not all the seeds are fully developed. Sizes of individual fruit in each bunch frequently vary considerably, with the largest locally-produced weighing ¾ oz (21 grams). A color photo of a Florida-grown langsat fruiting appears on the front cover of the Rare Fruit Council International 1979 Yearbook. The skin of the fruit contains a white, sticky, bitter latex that can adhere to the mouth and fingers when the langsat is eaten. Dipping the ripe fruit bunch in boiling water for a few seconds coagulates the sap and eliminates this problem. The green seeds, if accidentally bitten into, are extremely bitter.

Two langsat varieties introduced by the writer into South Florida and later fruited in his grove are the 'Conception' and the 'Uttaradit'. The 'Conception' was obtained from the Philippine Plant Industry in 1956 as a grafted plant. In these Asiatic islands, the langsat is highly regarded and goes under the name 'lanzone'. The scionwood of this Philippine clone was collected from the famous sweet variety of lanzones in a barrio named Conception, of Talisay, Negros Occ. First bloom appeared on the above grafted plant in 1976 without fruit set. No further flowering occurred until the spring of 1979, probably due to cold damage during the 1977 January freeze. This second bloom produced a crop of quality fruit that is thought to be of superior size and flavor. The tree is presently 18 feet high with an 11 foot spread, growing in full sun.

The langsat variety 'Uttaradit' was introduced from Thailand in 1957. The variety takes its name from a province N.W. of Bangkok where langsats grow in abundance. First fruiting of this marcotted plant occurred in October 1975 when the partially-shaded tree had obtained a height of 15 feet. This event marked what is thought to be the first instance of the langsat bearing on the Continental U.S.A. For the last two years, the tree has had a prolonged fruiting season extending from August through April. One possible explanation for this could be the nearly complete girdling of the base of the trunk by the 1977 freeze.

The langsat can be propagated from seed, cuttings, marcots and grafts. Seeds soon lose their viability and should be planted as soon as possible. Select and use only the largest, as germination and initial growth rate are related to seed size. A soil fungicide such as Banrot will insure better germination and prevent damping off. Cuttings can be rooted under mist or by potting up and covering over with clear plastic bags. Short, actively-growing tip cuttings about 3 inches to 4 inches long are preferred. Marcots, especially those taken from pot-grown plants in a greenhouse with 3/8-inch limb diameter or larger are easy to root. Regular grafts can be made, while approach grafts seldom fail. Plants grown from seed should be grafted to shorten the length of time required to bear.

Young plants, in the writer's greenhouse, have been observed to exude a clear, sweet-tasting liquid. This occurs in areas of rapid growth at the base of developing langsat leaf petioles. Small black nectar-eating ants are attracted to this and can become a nuisance. Occasional scale have been observed on developing fruit of the 'Uttaradit' variety but not elsewhere on the tree. A corky bark disease appeared on the trunk and larger limbs as the langsat trees matured in the writer's grove. This same problem has been observed by the writer on langsats grown on Florida's Big Pine Key near Key West, on a langsat planted at the University of Hawaii Kona Branch Experiment Station on the Island of Hawaii, and on a specimen tree cultivated in Tahiti, French Oceania. The disease is thought to be caused by a fungus canker (Cephalosporium sp.) with larvae (Tineidae sp.) under the affected bark feeding on the dead material. Various attempts at control have proved unsuccessful. The corky, loose bark can be removed, but this only gives temporary relief. It has been observed to be more severe under shaded growing conditions than in full sunlight. The same rough flaking bark symptoms have also appeared on the rambai (Baccaurea motleyana, Hook), another tropical fruit tree growing in the writer's collection.

The langsat is easily damaged by cold. During the 1977 January freeze, the writer's two largest langsat trees were nearly girdled by the low temperature. Wrapping the trunk from the ground up to a height of three or four feet with an insulating material could have prevented this injury. In Puerto Rico, Almeyda and Martin report grafted langsat trees bearing before their eighth year. In Florida the 'Uttaradit' variety took 18 years to fruit, or over twice as long. The 'Conception' variety was even slower to bear. This is because of the adverse winter weather in Florida during which the plants make little growth, no growth or even experience die-back. Almeyda and Martin state, "It (the langsat) will not tolerate extremely alkaline soils." They suggest one that is slightly acid to neutral. Unfortunately, the warmest areas in South Florida, as one approaches the coastline, nearly always have highly alkaline soils. This means that a low to neutral pH growing medium would have to be provided for this tropical fruit to succeed in such climatically favorable areas.

The langsat is seldom found in Florida rare fruit collections. Its distribution has been severely limited by this Asiatic fruit's special soil requirements, its susceptibility to cold and the prolonged time taken for it to fruit. Rare Fruit Council International member Adolf Grimal has grown the langsat on Big Pine Key to a height of 25 feet by using low pH Florida mainland soils. They would not survive on the existing indigenous Florida Key's marl and limestone soils. Carl W. Campbell, referring to langsats set out in the fields of the Agricultural Research and Education Center (formerly Sub-Tropical Experiment Station) at Homestead, stated "The plants did not grow well in the limestone soil here. They made poor growth and were chlorotic. Ultimately all of the plants died, some evidently as a result of poor adaptation to the soil and some as a result of cold injury during the winters of the 1950s and early 1960s."

The duku, with the same botanical name as the langsat, is usually preferred to the langsat because of the superior quality of its fruit, The santol (Sandoricum koetjape, Merrill), a closely-related fruit in the same family as the langsat, appears to have a better future in South Florida. This is because vegetatively-propagated santols can fruit in only a few years, are slightly more tolerant to cold weather and will survive on higher pH Florida soils. In spite of its limitations, the writer has found considerable pleasure in meeting the challenge of growing and fruiting the langsat in Florida. What's more this exotic fruit is quite good to eat!

EDITORIAL: The climate of Florida is quite similar to coastal Southern Queensland and Northern New South Wales. So it is great to see this very tropical tree being grown in a sub-tropical climate.

DATE: November 1984

* * * * * * * * * * * * *