LYCHEE GROWING AND MARKETING IN SOUTH AFRICA

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Litchi chinensis

FAMILY: Sapindaceae

PRODUCTION

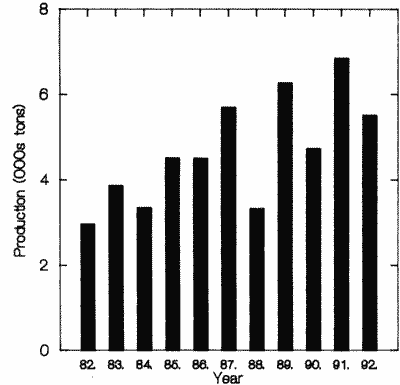

The lychee (litchi) industry in South Africa is well-established with a gradual rise in new plantings and output. Current production is about 8000 tonnes, with nearly half sold locally as fresh fruit on the Johannesburg and other markets (Figure 1). Depending on local market prices and seasons, about 4000 tonnes are exported annually. There is a good demand for exports to the United Kingdom, France and Federal Republic of Germany, although recently there has been strong competition from Madagascar. A small quantity of the crop is processed into juice, but due to the higher prices offered in the fresh market, the processing scene is under-supplied most seasons. The short harvest season reliance on a single cultivar, post-harvest losses and competition with Madagascar are the major constraints to the short-term future of the industry.

The lychee (litchi) industry in South Africa is well-established with a gradual rise in new plantings and output. Current production is about 8000 tonnes, with nearly half sold locally as fresh fruit on the Johannesburg and other markets (Figure 1). Depending on local market prices and seasons, about 4000 tonnes are exported annually. There is a good demand for exports to the United Kingdom, France and Federal Republic of Germany, although recently there has been strong competition from Madagascar. A small quantity of the crop is processed into juice, but due to the higher prices offered in the fresh market, the processing scene is under-supplied most seasons. The short harvest season reliance on a single cultivar, post-harvest losses and competition with Madagascar are the major constraints to the short-term future of the industry.

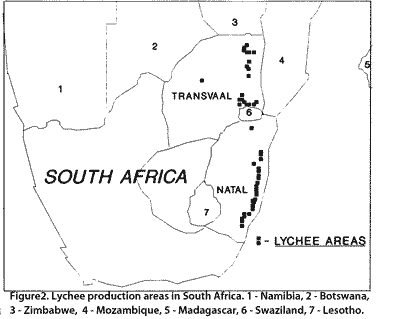

There is evidence that lychee trees were imported into South Africa from Mauritius in the early 1870s. From 1886 onwards, the Durban Botanic Gardens distributed air-layers of those introductions within the country, mainly for planting in Natal. The most important areas are the Eastern Transvaal Lowveld and Northern and North-Eastern Transvaal, and less so in the North and South Coast of Natal (Figure 2). There are about 250 growers with the average size of farms about 8 ha. The total area under lychees is about 1500 ha. New plantings continue to be made.

The best yields are found in areas with summer maxima of at least 23-24°C and relative humidity above 50%. These conditions reduce the incidence of fruit drop, browning and splitting. Average winter minimum temperatures are below 14°C in most areas. Rainfall is very seasonal, with a distinct dry period before flowering. Consequently, winter rest is not a problem in most districts, although unseasonal heavy rain before panicle formation reduces cropping some seasons. Relative humidity during spring and early summer is sometimes below 20% and this can reduce fruit set. Fruit cracking is also a problem.

CULTIVARS AND PROPAGATION

The industry is based more or less exclusively on cultivar H.L.H. Mauritius (a Tai So type) which accounts for 80% of plantings. Bengal (known locally as Madras or Red McLean) makes up the rest of the plantings. The performance and yield of cultivars from China, Taiwan, India and Florida have been disappointing. The main disadvantages with Tai So is its large seed. Because the commercial industry is dependent on a single cultivar, the season is unduly short. In some areas, the fruit ripen between Christmas and New Year when labour, transport and storage create problems.

Within a single orchard of Mauritius, there is usually considerable variation in fruit maturity amongst the trees, suggesting that air layers have been taken from seedlings. Increasing the length of the production season has a high priority for the South African industry. A program, based on promising early and late selections is in progress, which includes local selections as well as recently imported cultivars. The long-term aim is to breed new cultivars, with the assistance of controlled pollination. The long juvenile period by hybrid seedlings needs to be overcome to hasten the selection process.

Most trees are propagated by air-layering. Experiments over 20 years at Nelspruit indicate that grafted plants yielded no better than air layers, provided the latter are allowed to establish in the nursery for at least six months to develop a healthy root system. There is interest in the use of cuttings for the rapid multiplication of new cultivars, but it is not used commercially.

ORCHARD MANAGEMENT

Trees are planted at spacings of 12 x 12 metres (64 trees per hectare). Some growers plant at 6 x 6 metres and remove half the trees at year 15. There is interest in the planting of other crops (e.g. papaya) between the rows in the first few years of an orchard. Casuarina and Pinus are the most popular windbreak species. A soil sample prior to planting is usually recommended.

Pruning is limited to the removal of branches associated with weak crotch angles. A pole scaffolding is sometimes erected around the tree to reduce limb breakage associated with heavy cropping but only lasts a few years. Methods of tree size control including pruning in conjunction with controlled irrigation, cincturing and paclobutrazol are under evaluation. None of these techniques have consistently controlled tree size without reducing cropping at least in the short term.

Paclobutrazol may be registered soon for use in lychee in South Africa, after limited evaluation. In one experiment with 10-year-old Mauritius trees in the Lowveld there was a marked inhibition of vegetative growth in December and March with application of paclobutrazol the previous winter. Yields were not always increased after paclobutrazol. Recommended soil application rates are 0.2-4 g/m ground cover. Application time is late winter. Residues in the fruit are not a problem, although there is concern in Europe about chemical treatments of tree fruits.

The Institute for Tropical and Subtropical Crops (I.T.S.C.) at Nelspruit encourages the use of minisprinklers, although some trees are grown without irrigation. Because autumn and winters are normally dry, irrigation can be used to control growth and cropping. Available soil moisture is allowed to fall to 10% before irrigation during the period from April to the commencement of flowering in late June. During the remainder of the crop cycle, soil moisture is maintained above 50%. Maximum rates of irrigation are calculated from an estimate of crop water loss, although this method has shown to be unreliable in some areas. Scheduling irrigation with tensiometers is preferred, but is not widely practised. Water is mainly applied by flood irrigation, with the trees often suffering extremes of water supply.

Nitrogen and potassium fertilisers are applied before flowering and after harvest. Phosphorous is applied after harvest. Recommended amounts for well-grown 10-year-old trees are: 700 g N, 50 g P and 250 g K per tree per year. Rates of Nand K are low compared with Australian recommendations and may be partly responsible for the low average fruit size of Mauritius (21 vs 25 g in Australia). Many lychee orchards are low in zinc and boron, with the latter nutrient implicated in poor fruit set. Foliar sprays are recommended every two years (2 g zinc oxide/litre and 1 g borax/litre). Soil applications have not been tried.

Researchers have shown that very high rates of nitrogen depress yield, presumably because of excessive vegetative flushing in autumn. Highest yield are associated with a leaf nitrogen level of 1.47%, and lower yields with 1.42 or 1.52% N. This is close to the suggested range in Australia. There is strong interest in restricting N applications between panicle emergence and fruit set so to reduce excessive flushing prior to flowering in winter. Only slight responses to fertilizer phosphorus and potassium have been recorded.

Nutrition management is supported by leaf analysis annually together with soil analysis every two to three years for each block of trees. Leaves are sampled from behind the fruiting cluster about six to eight weeks after fruit set. Tentative leaf standards have been developed from limited trial work. The time of leaf sampling is later than in Australia which is after panicle emergence. However, the standards for both countries are similar if one takes into account the effect of season on leaf nutrient composition. Soil nutrient standards are not comparable because of different chemical analyses.

PESTS AND DISEASES

The lychee moth (Cryptophlebia peltastica) is the most serious pest. The moth has a similar life cycle to the macadamia nutborer (C. ombrodelta) with 10% damage in unprotected orchards. Sometimes damage is not noticeable until after harvest. We would expect greater damage with nutborer in Australia. Chemical control is with one spray of Alsystin (a chitin synthesis inhibitor) 40 days before harvest. The use of paper bags over the fruit also gives protection. Bags must be tied at least six to eight weeks before harvest. Other well-known host plants of the lychee moth are macadamia, Bauhinia, Caesalpinia and Acacia species.

The false codling moth, (Cryptophlebia leucotreta) has been recorded as a pest of lychee in South Africa, but the level of damage is usually only 1.0% in most orchards. The pest attacks a wide range of wild and cultivated host plants, and is a major economic pest of citrus. All stages of developing fruit can be attacked. Contemporary methods such as cultural control, monitoring or trapping with sex pheromones and the release of sterilized males have not yet been commercialized. Application of insecticides may be feasible only for major producers. Biological control is possible, particularly the use of egg parasitoids (e.g. Trichogrammatoidea cryptophlebia).

Fruit bats can devastate a crop, with the damage varying from area to area and orchard to orchard. The only successful control measure is the use of lychee bags which cover the bunches.

The coconut bug (Pseudotheraptus wayi) has a similar life cycle to fruit-spotting bug (Amblypelta lutescens and A. nitida) in Australia and has spread to several subtropical nut and fruit crops since 1977, causing fruit drop in early stages. However, it has not so far been reported in lychee.

Bark borers (Salagena sp.) and nematodes (Hemicriconemoides mangifera and Xiphinema brevicolle) have been associated with a tree decline. Two parasitic wasps have been found to help control bark borers. Chemical control is available for bark borers and nematodes.

Fruit fly is reported to damage lychee in South Africa and may be as high as 40% in untreated orchards. Two species are important, (Ceratitis capitica, Mediterranean fruitfly), and (Pterandrus rosa - Natal fruitfly). It was thought that larvae only develop in fruit already damaged by other pests, however, it is now known that the species can sting intact fruit as they begin to colour. Control is by the use of a malathion or trichlorphon protein hydrolysate bait spray, although some growers bag their fruit. The bait is applied at weekly intervals from just after normal fruit drop until a week before harvest. The bait is normally applied (in large drops) to one or two sides only of each tree, with about 1 litre/tree. The bait must be reapplied if it rains.

Paper bags are placed over the fruit clusters about 6 weeks before harvest. The bags offer control of fruit fly and lychee moth. Fruit are also reported to have better size, colour and appearance, and harvested later. Normally only the branches on the lower parts of the tree are bagged (about 10-20% of the crop). Fruit under bags are normally regarded as first class fruit and fetch a higher price. Bags cost about 7cents each and an average worker can bag about 400 to 600 bunches a day. Bagged fruit sometimes develop fungal lesions consisting of browning of the skin, watery areas and tearstains running from the stem end of the fruit. Several factors promote the development of the fungi: bagging too early in the season, enclosing leaves with the bunches and covering bunches when humidity is high. No more than 30 fruit should be enclosed per bag. Rain water should not be trapped in the bag.

The only major disease affecting lychee in South Africa is dieback caused by Armillaria. It is mainly confined to the high rainfall areas of the Northern Transvaal. Losses can be significant in individual orchards, although the disease is not widespread. There is no control at this stage.

HARVESTING AND MARKETING

Lychees mature between November and February with a peak in December and January. Picking is by hand and is difficult in some of the older orchards due to the size of the trees. Pickers are paid by weight of fruit harvested. The adults pick the lower fruit, teenagers the middle fruit and the youngsters scale the limbs to reach the top fruit. There are guards around most of the orchards to prevent people stealing fruit. Growers living close to the bush can lose considerable amounts of fruit to native animals including baboons.

Average fruit weight is 20 g, total sugars 15-17%, acidity 0.5% and sugar/acid ratio of 30-34. As in Australia, some growers market green fruit in an attempt to fetch high early prices of $10-12/kg. Most fruit for local consumption are packed in 2 kg boxes (without plastic wraps) although there is some early fruit in 250-300 g prepacks. Some of the larger growers have installed sorting and grading machines and cool rooms.

Post-harvest decay poses a serious problem to lychees in South Africa. Fungi are the prime cause of this decay. No fungicides have to date been registered for controlling these diseases. The problem of browning can be overcome by using refrigeration and with packaging in plastic bags.

The local market is currently the largest consumer of lychees. During the past season about 4000 tonnes was sold in the 14 municipal markets from November to February. The majority were sold in the traditional 2-kg package not treated with any preservative. Wholesale prices in November, December, January and February are R5.0, R3.0, R2.0 and R5.0/kg, respectively. Although there appears to be a general increase in consumption, it is extremely sensitive to volume. As soon as volume exceeds a certain level, prices tend to fall dramatically.

The export market to Europe and the U.K. is strong, accounting for about 40% of the South African crop. About 20% of the fruit is exported by air during the early part of the season for the high value pre-Christmas market. The rest of the crop is sent later by sea. Air freight to Europe costs R3/kg and sea freight about R0.60/kg. Fruit are usually consigned to export companies, rather than exported by individual growers.

Fruit shipped in refrigerated reefer containers must be treated with sulphur to prevent browning during transport. The fruit are placed in a closed container and 100-150 g sulphur per cubic meter of air burnt in the enclosed space. The sulphur dioxide fumes thus produced bleach the fruit to a pinkish-cream colour. They regain their red colour when exposed to the air. If the fruit are brown before bleaching or are bleached excessively to a green colour, they will not revert to the natural red colour. Fumigation is beneficial for fruit consumed within 1-2 weeks but holds no real benefit for longer storage. The process also has no fungicidal effects. There have been some problems with sulphur residues greater than the accepted maximum of 10 ppm in the pulp. Gaseous sulphur dioxide provides more controlled fumigation with lower residues of sulphur in the fruit. There has been some trials with acid-dipped fruit. Fruit for export must be a minimum of 30 mm in diameter, although in the last season this was reduced to 20 mm because of the prolonged drought in many areas.

The export market has better potential for growth than the domestic market. Lychees share in the growth of exotics on the European fresh fruit markets. In 10 years, lychee has become an important tropical fruit with about 10-15000 tons sold in Europe, putting it on par with papaya and ahead of passionfruit. South Africa has about a third of the market, and the rest mainly from Madagascar. Reunion and Mauritius account for about 3% of sales. Returns during the past season were on average R2.30/kg to the producer making this a very viable crop to grow. No promotion of the fruit has been initiated at this stage.

RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

The Institute for Tropical and Subtropical Crops (I. T. S. C.) at Nelspruit in the eastern Transvaal has the major responsibility for lychee research in South Africa. Trials are also carried out at Burgershall nearby. Together, the two stations have one graduate and two technicians working on lychee, but they also have responsibility for other crops including macadamia. Research on lychee includes plant introduction and evaluation, development of cutting and grafting techniques and methods of tree size control.

INDUSTRY ORGANIZATION

Growers are represented by the South African Litchi Growers' Association (SALGA) which was formed in 1988. The association has a Research and Technical Committee to attend to the immediate problems in the industry. SALGA allocates funds to both pre- and post-harvest research from voluntary levies collected from growers. It also holds a Litchi Research symposium every second year, and produces an annual Yearbook, and several Newsletters per year.

Bibliography

Anonymous, 1992. The cultivation of litchis. Bulletin of the Agricultural Research Council Pretoria. pp 61.

Menzel, C.M., 1990. The lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) in South Africa, Reunion and Mauritius. Queensland Department of Primary Industries. pp 18.

Oosthuizen, J.H., 2001. Lychee cultivation in South Africa. Yearbook of the Australian Lychee Growers' Association. 1, 51-55.

DATE: July 1995

* * * * * * * * * * * * *