THE MAMEY

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Mammea americana

FAMILY: Guttiferae

The current active and widespread interest in the chemical properties of plants has given new importance to certain species that have held for many years a minor position in our horticulture, with little more than a glamour status as "rare fruit trees." One of these is the mamey (Mammea americana L.; family Guttiferae), also known as mammee, mammee apple, mamey de Santo Domingo, mamey de Cartagena, Saint Domingo apricot, South American apricot, Zapote de niño, etc. This species is often confused with the sapote, or mamey colorado (Calocarpum sapota Merr.; family Sapotaceae) which is commonly called mamey in Cuba; and reports of it occurring wild in Africa are due to confusion with the African mamey (M. africana Sabine; syn. Ochrocarpus africanus Oliv. )

ORIGIN AND DISTRIBUTION

The mamey is native to the West Indies and northern South America. It is commonly cultivated in the Bahama Islands and the Greater and Lesser Antilles. In St. Croix, it is spontaneous along the roadsides where seeds have been tossed. In Central America, it is sparingly grown except in the lowlands of Costa Rica and in Guatemala, where it may be seen planted as an ornamental shade tree along city streets. In El Salvador, it is found at altitudes ranging from 750 to 2800 feet. Cultivation is scattered through the Guianas, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, northern Brazil and southern Mexico.

Introduced into the tropics of the Old World, it is of very limited occurrence in West Africa (particularly Sierra Leone), southeastern Asia, Java, the Philippines, and Hawaii. All seedlings planted in Palestine have died in the first or second year. It has been nurtured as a specimen in English greenhouses since 1735. From time to time, seedlings have been planted in California, but most have succumbed the first winter, according to Dr. Robert Hodgson of the University of California, who stated in 1940: "I know of only one large and old tree of Mammea americana growing out of doors in southern California and it has never fruited."

The mamey may have been brought to Florida first from the Bahamas. One of the largest fruiting specimens in Florida is at the Fairchild Tropical Garden, standing on a site formerly part of an early nursery, and thought to be about 40 years of age. Another, as old or older, on a private estate in Palm Beach, was fruiting heavily before 1940. The most northerly reached 30 feet and fruited in Dr. Talmadge Wilson's garden at Stuart, but was killed by lightning about 1956.

There was a 35-foot fruiting tree in the Edison Botanical Garden at Fort Myers, its trunk at least 20 inches thick. Robert Halgrin, Superintendent, reports that this tree was removed after severe hurricane damage in 1960 and replaced by a young one now about 12 feet tall. Other mature fruiting specimens exist at the Miami City Cemetery and at Coral Way Gardens, Miami, and there is a non-fruiting one in Coral Gables on East Ponce de Leon Blvd. A large pair, one prolific and one non-fruiting, formerly stood in the Spreading Oak Nursery owned by Julius Grethen, 3179 Douglas Rd., in Coconut Grove. These and a fruiting seedling on the Harvey property next door were destroyed about six years ago to make room for construction.

Many seeds from the Grethen tree were planted as nursery stock by Robert Newcomb of Homestead, who offered plants grafted to the Harvey variety for sale from 1953 to 1956 and then, discouraged by winter-killing, gave his remaining plants to a garden club on Key Largo. Hurricane Donna of 1960 doubtless eliminated most of these. At Palm Lodge Tropical Grove in Homestead, Mr. Albert Caves has two 9-year-old seedling-grafts from the Grethen tree, and one has bloomed. Mr. Caves recently grafted four or five seedlings in cans at Coral Way Gardens, inserting buds from the highly productive parent tree.

In addition to the known trees already mentioned, there is a young seedling in the field at the Subtropical Experiment Station, Homestead, where three trees were killed by a temperature drop to 28°F. in January, 1950. There is a 15-foot tree at the home of Donald Gordon in South Miami, which flowered this year for the first time, and two at the Fairchild Tropical Garden about 10 feet high, and one of these has bloomed. The Garden has distributed numerous seedlings from their large tree at December meetings, but most apparently fail to survive the winter in the hands of new owners.

DESCRIPTION

The mammey tree, a handsome evergreen to 60 or 70 feet, greatly resembling the southern magnolia, has a short trunk, which may attain 3 or 4 feet in diameter, and ascending branches forming an erect, oval head, densely foliaged with opposite, glossy, leathery, dark-green, broadly elliptic leaves, up to 8 inches long and 4 inches wide. The fragrant flowers, with 4 to 6 white petals and with orange stamens or pistils or both, are 1 to 1½ inches wide when fully open, and borne singly or in groups of 2 or 3 on short stalks. They appear during and after the fruiting season; male, female and hermaphrodite together or on separate trees.

The fruit, nearly round or somewhat irregular, with a short, thick stem and a more or less distinct tip, or merely a bristle-like floral remnant at the apex, ranges from 4 to 8 inches in diameter, is heavy and hard until fully ripe when it softens lightly. The skin is light brown or grayish-brown with small, scattered, warty or scurfy areas, leathery, about 1/8 inch thick and bitter. Beneath it, a thin, dry, whitish membrane, or 'rag,' astringent and often bitter, adheres to the flesh. The latter is light or golden-yellow to orange, non-fibrous, varies from firm and crisp and sometimes dry to tender, melting and juicy. It is more or less free from the seed, though bits of the seed-covering, which may be bitter, usually adhere to the immediately surrounding wall of flesh. The ripe flesh is appetizingly fragrant and in the best varieties, pleasantly subacid, resembling the apricot or red raspberry in flavor. Fruit of poor quality may be too sour or mawkishly sweet. Small fruits are usually single-seeded; larger fruits may have 2, 3 or 4 seeds. The seed is russet-brown, rough, ovoid or ellipsoid and about 2½ inches long. The juice of the seed leaves an indelible stain.

PROPAGATION AND CULTURE

Seeds germinate in 2 months or less and sprout readily in leaf-mulch under the tree. Seedlings bear in 6 to 8 years in Mexico, 8 to 10 years in the Bahamas. While seeds are the usual means of dissemination, vegetative propagation is preferable to avoid disappointment in raising male trees and to achieve earlier fruiting. In English greenhouse culture, half-ripe cuttings with lower leaves attached are employed. No mention of grafting is found in the literature, though Munsell, et al. say the fruit in Guatemala is "largely from seedling trees". As already stated, grafting has been successfully performed in Florida by Caves and Newcomb. There is no published information available on cultural practices apart from the fact that the tree requires protection from cold during the first few winters, being considered somewhat tenderer than the mango. It favors deep, rich, well-drained soil, but is apparently quite adaptable to even shallow, sandy terrain.

SEASON AND HARVESTING

In Barbados, the fruits begin to ripen in April and continue for several weeks. The season extends from May through July in the Bahamas, some fruits being offered in the Nassau native market and on roadside stands. In South Florida, mameys ripen from late June through July, and into August. In Puerto Rico, some trees produce two crops a year totalling 300 to 400 fruits. Central Colombia has two crops occurring in June and December.

Ripeness may be indicated by a slight yellowing of the skin or, if this is not apparent, one can scratch the surface very lightly with a fingernail. If green beneath, the fruit should not be picked, but, if yellow, it is fully mature. If fruits are allowed to fall when ripe, they will bruise and spoil. They should be clipped, leaving a small portion of stem attached.

PREPARATION

To facilitate peeling, the skin is scored from the stem to the apex and removed in strips. The rag must be thoroughly scraped from the flesh which is then cut off in slices, leaving any part which may adhere to the seed and trimming off any particles of seed-covering from the roughened inner surface.

The flesh of tender varieties is delicious raw, either plain, in fruit salads, or served with cream and sugar or wine. In Jamaica, it may be steeped in wine and sugar for a while prior to eating. In the Bahamas, some prefer to let the flesh stand in lightly salted water "to remove the bitterness" before cooking with much sugar to a jam-like consistency. The writer has seen no necessity for pre-cooking treatment and simply stews the sliced flesh with a little sugar and possibly a dash of lime or lemon juice.

In our recent instance, some of the pulp, stewed without citrus juice, was left in a covered plastic container in a refrigerator for one month. At the end of this time, there was no loss of flavor, no fermentation or other evidence of spoilage; and the fruit was eaten by the writer with no ill effect. In this connection, it is interesting to note that an antibiotic principle in the mamey was reported by the Agricultural Experiment Station, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, in 1951.

Sliced mamey flesh may also be cooked in pies or tarts and seasoned with cinnamon or ginger. Canned, sliced mamey has in the past been exported from Cuba. The mamey is widely made into preserves such as spiced marmalade and pastes and used as a filler for products made of other fruits. Slightly underripe fruits, rich in pectin, are made into jelly. In the French West Indies, an aromatic liqueur called 'Eau de Creole', or 'Creme de Creole', is distilled from the flowers and said to act as a tonic or digestive. Wine is made from the fruit pulp and fermented 'toddy' from the sap of the tree in Brazil.

See Mamey recipes in the Recipes Index.

EDIBILITY OF PULP

The writer has been told by Dominicans that rural folk in the Dominican Republic have some doubt of the wholesomeness of mamey pulp. In the Description and History of Vegetable Substances Used in the Arts and Domestic Economy, published in London in 1829, it is stated: "To people with weak stomachs, it is said to be more delicious than healthful". Oris Russell, Director of Agriculture, writes: "I have never heard of the fruit causing illness in the Bahamas, although it used to be eaten widely by children and adults." However, the writer, when living in the Bahamas in 1944-45, received the impression that the practice of soaking the pulp in salted water was something of a safely precaution, inasmuch as bitterness was not only disliked but distrusted. The old Jamaican custom of steeping in wine might also be considered a safeguard.

Kennard and Winters observe that, in Puerto Rico, "Although the fruit is widely eaten, it is recommended that only moderate amounts be consumed". Prof. U.H. Williams, of the University of Miami's Modern Language Dept., relates that when he was about 19 in Mayaguez, P.R., he ate half of a large mamey from a tree in his home yard, after peeling and scraping off the rag but not removing any adherent seed-covering. Then he ate the pulp of one star apple. An hour later, he had stomach cramps and, later, his abdomen was reddened and oddly reticulated. He attributed this reaction to the mamey and was convinced there was "something poisonous about it".

Ten years ago, three Puerto Rican chemists, in an article entitled "Es el Mamey una Fruta Venenosa?", commented that, while the delicious mamey "has formed part of the diet of the inhabitants of the Caribbean Islands for many generations, it is well known that this fruit produces discomfort, especially in the digestive system, in some persons." They reported also that "a concentrated extract of the fresh fruit" proved fatally toxic to guinea pigs, and was also found poisonous to dogs and cats. The extract was made from the edible portion only. The authors likened the mamey to the akee as a human hazard, and Djerassi, et al., state that "reports of poisoning in humans are known".

INSECTICIDAL VALUE OF LEAVES, SEED, BARK AND GUM

That various parts of the mamey tree contain toxic properties has been long recognized, and was first reported by Grosourdy in 'El Medico Botanico Criollo' in 1864. A Colombian decoction of mamey resin was displayed at the Paris Exposition in 1867. It is significant that in the U.S. Department of Agriculture' s record of mamey seed introduction from Ecuador in 1919, only the insecticidal and medicinal uses of the species were noted. There was no comment on edible uses of the fruit.

In Puerto Rico, there is a time-honored practice of wrapping a mamey leaf like a collar around young tomato plants when setting them in the ground to protect them from mole crickets and cutworms. The leaf must be placed at just the right height, half above ground and half below.

In Mexico and Jamaica, the thick, yellow gum from the bark is melted with fat and applied to the feet to combat chiggers and used to rid animals of fleas and ticks. A greenish-yellow, gummy resin from the skin of immature fruits, and an infusion of half-ripe fruit are similarly employed. The bark is strongly astringent and a decoction is effective against chiggers. In Ecuador, animals with mange or sheep ticks are washed with a decoction made by boiling the seed but, in one instance, a dog with mange and ulcers died 48 hours after two applications.

In El Salvador, a paste made of the ground seeds is used against poultry lice, mites, and head lice. In the Dominican Republic, mamey seeds, avocado seeds, and Zamia seeds fried in oil, are mashed and applied to the head as a 'therapeutic shampoo,' probably to eliminate lice.

At the Federal Experiment Station, Mayaguez, P.R., the insecticidal activity of various parts of the mamey tree and the fruit have been under active investigation for more than 18 years. The seed kernel, most potent, was found, in feeding experiments and when tested as a contact poison applied as a dust or spray, to be effective in varying degree against armyworms, melonworms, cockroaches, ants, drywood termites, mosquitoes and their larvae, flies, larvae of diamondback moth, and aphids. In certain tests, mamey seeds appeared to be 1/5 as toxic as pyrethrum and less toxic to plant pests than nicotine sulfate and DDT. When powdered seeds and sliced unripe fruit infusion (1 lb. in a gallon of water) were tested on dogs, both products were as effective as DDT and faster in killing fleas and ticks but not as long-lasting in regard to reinfestation. None of the dogs was poisoned despite the presence of healing sores and minor abrasions of the skin, but, after similar trials on mice, 4 out of 70 died. The active ingredients of the infusion are the resin from the unripe skin and the developing seeds.

The dry and powdered immature fruit, the bark, wood, roots and flowers showed poor insecticidal activity; the seed hulls appeared inert. The powdered leaves were found 59% effective against fall armyworms and 75% against the melonworm. Various extracts from the fruit, bark, leaves or roots are toxic to webbing clothes moths, black carpet beetle larvae and milkweed bugs.

In fish-poisoning experiments, Pagan and Morris reported mamey seed extracts to be 1/30 as toxic as rotenone; 1/60 to 1/80 as potent as powdered, dried derris root. Feeding trials have shown the seeds to be very toxic to chicks, and they are considered a hazard to hogs in the Virgin Islands.

The crude resinous extract from powdered mamey seeds, given orally, produced symptoms of poisoning in dogs and cats and a dose of 200 mg. per kilogram weight caused death in guinea pigs within 8 hours. The crystalline insecticidal principle from the dried and ground seeds, potent even after several months of storage, has been named 'mammein' and assigned the formula C22H2805.

The stability of this principle was demonstrated by M.P. Morris, who found no significant difference in toxicity of powdered fresh mamey fruit and mamey powder stored for 6 years in steel drums. Neither was the potency of mamey extract destroyed by subjection to 200°C.

Extensive chemical experiments with the extracted compound are reported by S. P. Marfey in Part I of his doctoral thesis, Wayne State University, 1955. According to Marfey, the growing interest in 'mammein' is due to the scarcity of plant insecticides such as pyrethrum and rotenone. However, Puerto Rican scientists conclude that, when the latter are not readily available, the mamey can be resorted to as an inexpensive insecticide for local use in tropical America.

MEDICINAL USES

In Venezuela, the powdered seeds are employed in the treatment of parasitic skin diseases, as is the gum from the trunk in Cuba. The gum is valued by Indians as a cure for itch. In Brazil, the ground seeds, minus the embryo, which is considered convulsant, are stirred into hot water and employed as an anthelmintic for adults only. An infusion of the fresh or dry leaves (one handful in a pint of water) is given by the cupful over a period of several days in cases of intermittent and remittent fever and it is claimed to have been effective where quinine has failed.

NATURE AND USES Of MAMEY WOOD AND TANNIN

The heartwood is reddish- or purple-brown; the sapwood much lighter in color. The wood is hard, heavy, but not difficult to work; has an attractive grain and polishes well. It is useful in cabinetwork, also for construction and fence-posts, since it is fairly decay-resistant . It is, however, highly susceptible to termites. Some of the wood is consumed as fuel. The tannin from the bark is sometimes used for home treatment of leather in the Virgin Islands.

Illustration on the right by Jenny Taranto from Exotic Tree Fruits Book by Glenn Tankard.

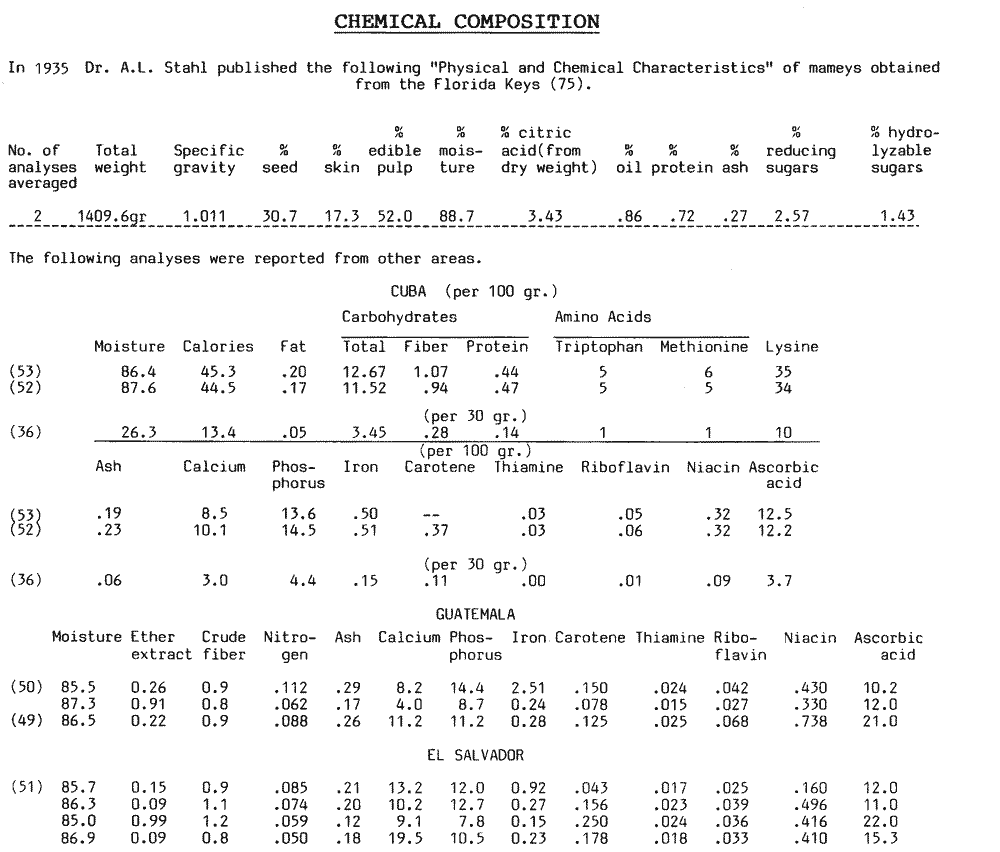

DATE: September 1988

* * * * * * * * * * * * *