CAPULI CHERRY

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Prunus capuli, P. salicifolia or P. serotina

FAMILY: Rosaceae

Around highland villages from Venezuela to southern Peru, the capuli is one of the most common trees. Easily identifiable, it has been said to characterize the Andean region much as the coconut palm typifies tropical coasts.

Yet it is probably not an Andean native: capuli (pronounced Ka-poo-lee) is an Aztec word, and most botanists believe that Spaniards introduced the tree from Mexico or Central America in Colonial times. Whatever its origin, this attractive tree has become so popular that it is seen from one end of the Andes to the other, especially around Indian settlements. In fact, it is now cultivated much more in the Andes than in its probably northern homeland, and the fruit is often much larger and more flavorful.

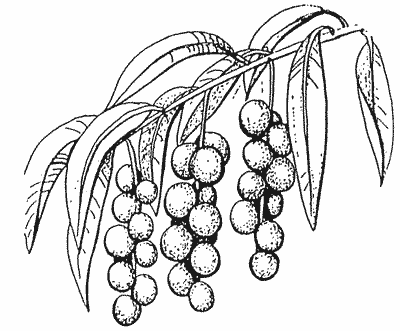

At harvest, capuli fruits are abundantly available in Andean markets. Capuli is a cousin of the commercial black and bing cherry, which it usually resembles both in appearance and taste. However, fruits are carried on short stalks and in bunches almost like grapes, and some taste like plums. They are round and glossy and are maroon, purple, or black in color. Their flesh is pale green and meaty, and most are juicy. The skin is thin, but sufficiently firm for the fruits to be handled easily without bruising. Although mostly eaten as fresh fruit, they can also be stewed, preserved, or made into jam or wine.

This fruit could become popular throughout much of the world. Although it grows in the Andes at tropical latitudes, it thrives there only in cool upland areas (2,200-3,100 m) at the Equator; fruit set occurs between 10-22°C. It is therefore a plant for subtropical or warm temperate regions. Some newly introduced specimens are growing particularly well in northern areas of New Zealand, where little or no frost occurs.

Despite its promise, the fruit also has a down side. The pit is rather large in proportion to the size of the fruit. Also, there is usually a trace of bitterness in the skin. However, in the best varieties it is so slight as to be unobjectionable and the fruits compete well with imported cherries.

It is curious that this fruit doesn't have more negative features because it has scarcely benefited from concentrated horticultural improvement and so far has been propagated primarily by seed. This is not because of any inherent difficulty: both grafting and budding are easy and successful, and the plant also roots easily from softwood cuttings.

The tree is extremely vigorous. It sets flowers and fruits heavily in its third - or even in its second - year of growth. It eventually reaches 10m or more in height. Apparently, it is not exacting in its soil requirements and grows well on any reasonably fertile site. It can thrive in poor ground, even clays, and seems to prefer dry sandy soils. Although resistant to damping-off, powdery mildew, and other seedling diseases, it is susceptible to the common black knot fungus and does not thrive in wet areas (areas receiving 300-1800 mm are said to be best in Ecuador).

Apart from bearing fruit, this is a useful, fast-growing timber and reforestation species (because it produces in poor soils, cost of production is also lowered). A few years after planting, its wood is suitable for tool handles, posts, firewood and charcoal. After 6-8 years it yields an excellent reddish lumber for guitars, furniture, coffins and other premium products. The wood is hard, is resistant to insect and fungus damage, and sells at high prices. Young branches are supple and strong, like willow canes, and the prunings are often used to make baskets.

Capuli seems particularly suitable for agroforestry systems. Its deep roots help prevent erosion, and it may not dry the soil. It can be inter-planted with field crops such as alfalfa, corn, and potatoes. It is a good plant for wind protection and it acts like a biological barrier - the birds enjoy its fruits so much they leave nearby crops alone.

Notes: Locally the fruit is often just termed 'cherry' ('cereza' or 'guinda'). Little-used Quechua names are 'murmuntu' and 'ussum'. In English, it is sometimes called 'American cherry'.

The name Prunus capuli is used extensively in agricultural and horticultural publications. Research indicates that the capuli is actually a large-fruited subspecies of the North American black cherry, formally designated as Prunus serotina subsp. capuli.

Editor's Notes: The above is only the first part of the "Lost Crops" article on the Capuli Cherry. The fruit is also sometimes called the Capulin, or Prunus salicifolia or Prunus serotina Ehrh. subsp. capuli (Cav.) McVaugh). However, the name Capulin is also applied to two other quite unrelated fruits, Muntingia calabura (from Tropical America) in the Elaeocarpaceae Family and Eugenia acapulescens (from Mexico) in the Myrtaceae.

DATE: January 1993

* * * * * * * * * * * * *