GROWING OLIVES IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Olea europaea

FAMILY: Oleaceae

Introduction

So you want to grow olives! The first question you must ask is why? Are you one of the many potential growers caught up in the current world-wide interest in olives and olive oil? It is important to know where you sit in the process. Are you an enthusiast or a serious grower? Do you wish to concentrate on the table market with pickled olives or is olive oil manufacture your goal? Do you want an income, profit or investment?

Why is there so much current interest in growing olives in Australia and elsewhere? The most important part of the olive tree is the fruit. The fruit when crushed and pressed yields the valuable edible oil, Virgin Olive Oil, which when eaten as part of the Mediterranean diet reduces the risk for heart disease and some cancers. Antioxidants such as polyphenols and Vitamin E together with a high proportion of monounsaturated fats are thought to provide this protection. Such health benefits have increased the demand for olive oil and together with relatively lower production by traditional producing countries has resulted in an increase in olive oil prices which has made olive growing more attractive. Concern has been shown in some quarters that olives may be the flavour of the month and their demise will follow other new industries such as tea tree oil, jojoba and emus. The major difference is that olives are a recognised international food commodity.

Economics of the Olive Industry

Twenty olive trees, which can be grown on a modest size block, are all you need to be self sufficient in eating olives and olive oil. Depending on the spacing between trees one can plant 100 to 300 trees per hectare. Scoping the type of Australian grower interested in olives reveals three classes:

• Lifestyle - 100-500 trees

• As part of existing horticultural or farming activities - 1000-2000 trees

• Specific olive operations - more than 5000 trees

Profitability will depend on marketing, quality of products, labour and infrastructure costs. Scenarios developed by Farnell, Hobman and others indicate that olive growing and olive oil production can be profitable under dryland or irrigated conditions. Australia im- ports about 17000 tonnes of olive oil per year for the domestic market. Compared to this, domestic production is negligible. Imports translate to less than one litre of oil consumed on average by Australians each year. There is therefore scope for import replacement as well as extending the use of olive oil. It has been estimated that the average Greek citizen, consumes about 20 litres of olive oil per year. As oil and fat consumption, from a dietary point of view is relatively constant on a per capita basis, eating more olive oil means eating less butter, margarine or vegetable oils. As the latter tend to be less expensive they will always be competitors even though olive oil has recognised health benefits.

As a foodstuff, olive oil is popular world-wide and as well as an anticipated increase in consumption by those with a western type of lifestyle an increase in consumption by Asians is expected. However as an edible oil it only represents 4% of the total world edible production with a yearly production of nearly two million tonnes. World production of olive oil has been dependent on traditional growing countries and because of their rising labour costs as well as local factors such as urbanisation effects and climate, shortages and increased prices have occurred. Interest by countries, such as Australia, with suitable growing conditions for olives is escalating because of the opportunity to produce olive oil and other olive products for the domestic and international markets.

An innovative, well-structured industry, supported by government agencies is essential for Australia to be a significant international player. The Australian wine industry will be a useful model for the olive oil industry to consider. A major Australian olive industry will only develop if growers and producers can deliver quality products in volumes large enough to meet supermarket and food industry demands.

Where do Olives Grow?

The olive and olive oil industry is predominantly based around the Mediterranean Basin. The olive tree, a dryland evergreen tree suited to the Mediterranean climate, grows under a wide range of conditions. Olive trees grow in arid and semi arid regions where they are resistant to adverse conditions tolerating drought, infertile soils, and salty conditions.

Reference to olives and olive oil is made some 200 times in the Bible! The wild olive Olea europaea L. subsp. sylvestris is believed to have been domesticated in Asia Minor by 4000 BC. The domesticated form of the olive is termed the European olive or Olea europaea L subsp. europaea. The olive was introduced and cultivated predominantly in countries of the Mediterranean Basin including Turkey, Greece, Italy and Spain as well as north African countries such as Tunisia and Morocco. The olive is known by a number of different names which can appear on packaged products such as preserved olives or olive oil.

• Arabic - ceiton, zeitoun

• Greek - elia

• Italian - oliva

• Spanish - aceituna

The olive is a subtropical tree and outside of the traditional producing countries, olives will grow well in climates with cool winters and hot dry summers such as in southern Australia. Suitable growing conditions exist in parts of the USA, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Brazil, and South Africa. There are also olive growing activities in New Zealand, India and China.

Olives grow under a wide range of conditions in Australia and new plantings are being made in every state including Tasmania and the Northern Territory.

The Olive Tree

The olive tree is traditionally grown under dryland conditions where water is delivered through natural precipitation. Special leaf adaptation will allow water absorption as well as conserve water during dry conditions. Rainfed olive trees require 500-600 mm annual precipitation although in countries such as Tunisia which have less rainfall there is an active olive industry. Higher rainfalls are beneficial in ensuring continuity of crop. Supplementary water is very beneficial in hot dry months particularly for young trees and when the fruit is developing. With an adequate water supply for irrigation, limiting factors for optimal olive fruit production are the temperature and soil conditions.

Left unattended, olive trees can survive for at least 500 - 1000 years and can easily reach 10m in height. Such tall trees are not suitable for modem olive fruit production where heights of up to 5 m are more suitable for hand or machine harvesting. Future groves which will involve a greater degree of mechanisation for picking and pruning for cost effective production, may very well have the olives in hedgerows 1-2 m high with up to 500 trees to the hectare. Groves being developed currently have about 250 trees/Ha which is in marked contrast to the 100 or so trees/Ha in traditional groves of the Mediterranean countries. Research is required to evaluate such new intensive growing procedures for olives.

Olive fruits develop after fertilisation of the small cream to white flowers. Sexually, olives are hermaphrodite with both male and female flowers present on the one tree. However self pollination and cross pollination can occur. Most pollination takes place either by falling pollen or wind-carried pollen. Bees may be involved in the pollinating process to a lesser extent. Mixed cultivar groves with specific pollinating cultivars such as Pendolina at a ratio of 1 to 8, are included in an olive grove because of their superior pollinating capacity. Some flower infertility occurs in association with ovary abortion, ineffective pollen, absence of pollen or incompatible pollen. High temperatures (40° C) can damage flowers. Flower drop is greater when olives are grown under dry land conditions than when they are irrigated.

Without irrigation the fruit-bearing age of the olive tree is about 9 years. This period can be halved when the olive trees are grown under intensive conditions including irrigation and fertilisation. The fruiting age is also cultivar dependent. Olive trees are alternate year bearing, with a heavier crop being produced every second year. Alternate year bearing can be evened out with irrigation.

Climate

Because olives grow well between latitudes 30 - 45, both in the northern and southern hemispheres, significant areas of Australia have the climatic conditions suitable for olive growing. Much of this land is already being used for agriculture, part of catchment areas or set aside for national parks. Although there is limited scientific documentation on olive performance in Australia, there are sufficient plantings in a wide range of locations indicating successful olive growing in south-west Western Australia, southern New South Wales, southern South Australia and parts of Victoria. Early plantings began with the colonial settlers who introduced a variety of trees to help in their survival. Many old homestead still have several olive trees which have cropped for over 150 years, even though the animals may have always been the beneficiaries.

Temperature

Olive trees do not tolerate temperature extremes. The most favourable temperature range for olive growth is 15 - 34° C which is common in Australia. High temperatures damage flowers and cause marked flower drop and hence influence fruit production whereas low temperatures and frosts can kill tissue and damage fruit. Below a base temperature of 10°C growth is restricted and when the temperature falls below -5°C, such as in severe frosts, tissue necrosis occurs, although roots and below-ground structures may survive. Some cultivars are more resistant to frost than others. Frost damaged olive trees in Tuscany (-25°C) cut at the base have regenerated into productive trees. Of course it takes 2-3 years to reach previous production levels. Trees in poor shape due to stress or animal damage cannot handle frosts as well as healthy trees. Higher temperatures are detrimental, causing early maturity, poor fruit set and tissue destruction. Desirable upper temperature limits for day and night are 40°C and 20°C respectively. Irrigation can overcome some of the hot weather effects.

A midwinter mean temperature of below 10°C, is required for flower production but not essential for good growth. Even lower temperatures induce vegetative rest. Ideally olives should be grown in areas where temperatures do not fall below 5°C or above 40°C. Both short and long days are required during the growing period. This can be achieved easily in southern Australia. Olive trees growing closer to the equator tend not to fruit and grow vegetatively. This is in part due to the lack of a chilling period required for flower development.

As mentioned previously, olives are a dryland plant and are quite resistant to drought conditions similar to the levels of rainfall experienced in large areas of rural Australia. Under rainfed conditions where water supply is low, alternate bearing is more pronounced and in some years there may be no crop at all. Providing supplementary water during lengthy dry periods, November to February in southern Western Australia, is very beneficial and allows for more consistent cropping.

Shade Effects

Olive trees are intolerant to shade. Leaf photosynthesis occurs throughout year as long as temperatures do not fall significantly during winter. Direct sunlight is required for adequate flowering and fruit production. Reduced light lowers the level of bud induction and differentiation. There is much discussion about the spacing of olive trees in groves. Factors that must be considered when planning an olive grove include water and nutrient competition, mechanisation procedures and shading effects. There is always the desire to plant as many trees as possible per hectare. Traditional groves may have had as few as 50 trees/hectare. Modern groves can have in excess of 250 trees/hectare. Such intensive groves may suffer shading problems particularly if trees are not trained and allowed to grow unchecked.

Salt and Wind Effects

Olives are moderately tolerant to salt spray and salt in root zone. Olive trees will crop if irrigated with saline water with a conductivity of 2,400 mS/cm. However trees receiving 3- 4 times this level have been unable to resist persistent frosts and a number of olive trees and other species died.

Olive trees have been used successfully as windbreaks on farming properties. Strong winds, 80-100 km/h are extremely harmful for crop production. Hot drying winds coming off the desert areas can induce water stress in olive trees with the leaves and flowers being particularly affected. Such wind damage can be minimised with irrigation.

Soil Requirements

A wide variety soils will support olives including calcareous soils. Deep soils, 40+cm, are the most suitable although more shallow soils, 21-40 cm, can be modified to support growth. Very shallow soils, <20 cms, are generally not suitable.

Soil pH

Soil pH is an important factor. Weakly acidic soils, pH 5.5-7, are the most favourable with soil pH up to 8.5 being suitable. Soil with an acidity of pH <5.5, which is often found on previously farmed land, can be modified with dolomite to give a more suitable growing pH.

Essential Nutrients

Nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium are the most essential nutrients and need to be applied if the soil is inadequate. Levels need to be monitored because nitrogen leaches out readily. There is a downside because overuse of nitrogen can result in excessive shoot growth producing numerous small fruit. When adding phosphate, the soil pH needs to be considered because phosphate availability is reduced in acidic soils and alkaline soils high in calcium. As a guide one should aim for a soil pH of 6-7.

Trace Elements

Trace elements required by olive trees include calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, sulphur and zinc. Availability is pH dependent with greater availability from acidic soils. Where soils are alkaline or calcareous, complexes are formed so using foliar sprays is the better way to go.

Drainage

Fast drainage is important for olive trees as they do not like "wet feet". Flooding, particularly through the growing season leads to root anoxia and necrosis. Water logging for more than a few days can eventually lead to loss of trees. When planning an olive grove, trees should be planted in well draining areas. If waterlogging is a problem, contour channels should be established to allow adequate drainage of water. Poorly draining clay soils are prone to water-logging, particularly in winter and early spring. Experience on the east coast of Australia indicated that excessive summer rain in association with poorly draining clay soils is particularly detrimental to olive trees. Under anaerobic conditions created toxic substances such as hydrogen sulphide and methane are formed by microorganisms.

There is also reduced bioavailability of trace elements. Effects include poor shoot growth, stunted growth, yellowing of foliage and tree death. Olive trees with root damage are less able to cope with the cold because of reduced carbohydrate storage and are more susceptible to fun- gal infection. Waterlogging is less of a problem with sandy soils. Uniform loam is the best for growing olives, whereas loam or sand over clay are also suitable. With fast draining soils, irrigation should be adjusted to give less amounts of water more often.

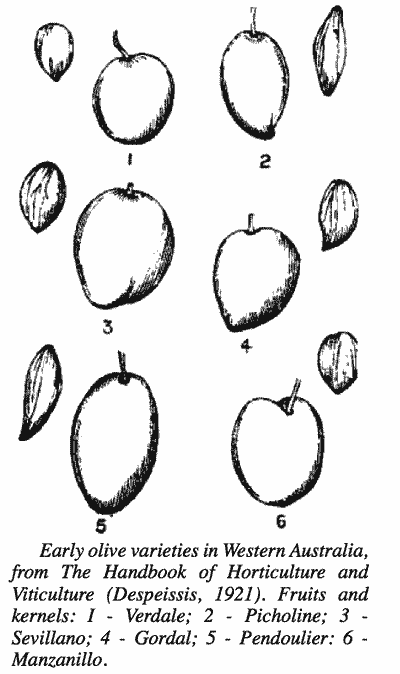

Cultivars

With over 800 named olive cultivars available world-wide, specific cultivars are selected on the basis of their usefulness for preserving as table olives or for making olive oil. Although all olive cultivars can be eaten or crushed for oil, those preferred as table olives generally have a greater water content and lesser oil content than those used to make oil. Table olives are usually larger than those for oil which makes the latter more difficult to pick by shaking. Future picking methods may follow technologies being developed for the grape industry. Furthermore each country has its own traditional cultivars such as Picual in Spain, Leccino in Italy and Kalamata in Greece. Some country specific cultivars are listed below.

| Algeria | - Sigoise |

| Australia | - Swan Hill (non-fruiting) |

| Chile | - Azapa |

| Cyprus | - Adrouppa |

| Egypt | - Aghizi Shami |

| France | - Picholine |

| Greece | - Kalamata, Koroneiki, Mastoides |

| Israel | - Barnea, Nabali, Souri |

| Italy | - Ascolana, Frantoio, Leccino, Pendolina, Carolea |

| Morocco | - Picoline Marocaine |

| Portugal | - Blanquita de Elvas, Cobranosa |

| Spain | - Arbequina, Picual, Sevillano, Manzanillo |

| Tunisia | - Chemlali |

| Turkey | - Memeli, Ayvalik, Domat |

| USA - | - Californian Mission, UC13A6 |

Cultivar selection for a grove can also be made on the basis of fruiting period, resistance to frost or disease and usefulness as root stock. In Australia for olive oil production there is interest in planting the cultivars Frantoio, Leccino, Pendolina, Picual and Paragon for oil production.

Newer cultivars for Australia, some of which are still in Australian quarantine, include Barnea (Israel), Koroneiki (Greece) and Minerva (Italy). These cultivars can be trained into medium sized trees, which are less labour intensive to manage. Fruit from these cultivars yield about 20-25% oil. There is also interest in developing DNA identified cultivars from wild olives growing in Australia as Australian cultivars.

It has been estimated that in olive oil production, cultivars contribute about 20% to the quality of the oil with most of the quality being attributed to regional effects, harvesting and the oil production process. The axiom is that you need high quality olives to produce high quality oil. If it is any consolation, less than one third of the olive oil produced world-wide meets the extra virgin standards. So world consumers are using lesser quality olive oils often labelled as olive oil or pure olive oil. The latter olive oils make up the bulk of olive oils marketed in Australia for table use and in the manufacture of olive oil margarines and blended oils. When Australia becomes a major olive oil producer, even though the industry will be aiming for the quality end of the market, facilities will need to be developed to process lesser quality olive oils to international standards.

In the case of table olives, consumers prefer a fleshy fruit with a high flesh to pit ratio. Olives that are recognised as excellent table olives include Kalamata, Volos, Sevillano and Manzanillo. All grow well in most parts of Australia although Manzanillo does better in warmer climates. There is no doubt that those wanting to grow table olives should consider the Kalamata variety. Verdale has also been a popular table olive in Australia in the past, however it will become less important as more new cultivars become available.

Olive Tree Propagation

Traditionally olive trees have been propagated by grafting onto seedlings. Grafting is still the preferred method for difficult to strike cultivars such as the Kalamata variety. For most cultivars, current practice is to strike pencil length vigorous shoots using indolebutyric acid. Several regimes are available. Commonly cuttings taken in autumn are dipped for a few seconds in IBA (3-4000 ppm), placed in a synthetic medium such as perlite or peat moss and then kept moist in a propagating house with intermittent fog and spray and bottom heat. Rooting takes 2-3 months, after which the rooted cuttings are planted out into plastic bags. For serious growers tree propagation should be left to the experts.

Olive Grove Design

There is much discussion regarding the spacings, planting protocols and form for olive trees. Several questions need to be asked.

Olive trees need maximum sunlight and training by selective pruning will ensure that the outer growing area of the crown where the olive fruit develops is maximised. Olives develop on one year old wood. Under rainfed conditions tree spacing needs to be greater than if irrigated to allow for effective root development. For example in countries with very low rainfall such as Tunisia, olive trees are spaced 20 m apart. A 9 m by 9 m spacing will allow a tree density of 120 trees/Ha whereas 6 m by 6 m planting will give 250 trees/Ha. For the UWA research trials we will be using a 5 m by 7 m planting design. Trees will be planted 5 m apart and the inter-row spacing will be 7 m. The reason for the latter is to allow for machinery to pass between the rows. For irrigated groves the inter-tree spacing can be reduced with increased risk of shading. Shading reduces budding and fruiting and orchard production.

Early in the development of an olive grove, the inclusion of filler trees has been suggested so that commercial yields will be obtained earlier. The idea is that these filler trees are re- moved as the main trees grow. The economics for such an exercise have not yet been proven, and unless there is a shortage of land, should not be considered. It is far better to plant the trees in their permanent position.

Planting Olive Trees

Olives grow on a variety of soils good and poor. Some planting regimes suggest deep ripping. This is more important where old root systems are present and for heavy and loamy soils likely to compact. Deep ripping is less important for sandy soils. Rotted organic material such as straw, animal manures, blood and bone worked in to the soil prior to planting has been shown to be advantageous. Some commercial growers also recommend the application of commercial formulations of slow release fertilisers. Where soils are phosphate deficient or acidic, superphosphate or dolomite can be worked into the soil. Although herbicides are suggested to keep down weeds, mulching is a more environmentally friendly process. Growing a winter legume for green mulch is another strategy that should be considered. More research is required to determine nitrogen production from biological sources to reduce the need to add chemical fertilisers and so reduce the risks of pollution. Mechanical tilling particularly after harvest assists in improving water absorption, however promotes erosion and loss of top soil and should not be the preferred method for weed control.

Least problems will occur if olive trees are planted in autumn or spring. When planting olives, a hole big enough to take the roots should be dug, avoiding any glazing of the sides. Trees should be planted at a level lower than the top of the soil in the pot or bag. Grafted olives, such as Kalamata variety, should have the graft planted well below the ground. This will reduce the risk of losing grafted stems as well as promote root formation from the grafted variety. Trees should be watered immediately after planting and every couple of weeks especially during prolonged hot dry periods. Apart from water some protection from sun and small animals may also be necessary. This can be achieved by painting the trunks with white house type plastic paint or by using milk canons. A stout 2 m wooden or metal stake can also be of some use in windy conditions and for training the olive trees.

Irrigation

Irrigation is essential for large commercial orchards. A planned irrigation regime will allow the orchard to develop faster, yield earlier than under rainfed conditions, increase the yield and reduce the biennial bearing effects. characteristic of the olive tree. The type of system used will depend on the availability of water, the soil type and the tree spacing. Water is required over the hot summer period particularly when the fruit is developing. One thing for sure, in hot dry areas it is better to give the olive trees the water than to waste it to evaporation. The irrigation period is generally between November and April. This will depend on whether the site receives winter or summer rain. If the natural precipitation is of the order of 500 mm annually, about 200 litres should be supplied to each tree twice a month. A more detailed analysis can be undertaken with an irrigation specialist who can evaluate specific situations.

Pruning and Training of Olive Trees

Although old olive groves have well established trees bearing excellent crops, they are of lower tree densities and trees more than likely have multiple trunks. This combination is labour intensive and quite unsuitable for modern groves.

With new plantings it is essential to provide them with proper care. Very little pruning is undertaken with young trees so that they will bear as quickly as possible. Newly planted olive trees should be trained in either the free form vase shape or the monoconical shape. In both cases it is essential that a single trunk is established. This can be achieved by removing laterals at convenient times leaving a single trunk, about one metre in height. The free vase form is better for hand picking whereas the monocone is more suited to machine harvesting.

For the free form vase shape, 3 to 5 lateral shoots are selected to provide the scaffold branches. Tree growth is promoted to follow the scaffold, thinning the internal growth to allow light penetration and hence better cropping. The monoconical shape is developed by training the main axis of the trunk as the leader. Here a stout stake is important to keep the leader erect. Laterals are trained to grow out from the leader in a lateral fashion. Such training is undertaken in the first years after planting. After that only light targeted pruning is required. The crown of the monoconical shape, which is believed to have a larger fruiting surface, develops quickly and upward. The latter aspect could be an advantage in more intensive plantings. The economics of the two pruning methods have yet to be revealed. One thing for sure, proper training reduces the need for more radical pruning later!

Trees pruned in the ways described above have smaller crown volumes than untrained trees and so can take advantage of the available light, particularly with closer plantings. Such training allows for the development of a strong branching scaffold which can cope with heavy cropping as well as providing an efficient system for mechanical harvesting. Another advantage is that fruit bearing is brought on earlier.

Olive trees need some pruning every 2-3 years. The objectives of pruning are to remove suckers from the base, dead wood and excessive internal growth to admit more light into the crown of the tree to improve fruit quality. Excessive pruning particularly from the periphery of crown can result in loss of new wood, lower yields and possible sunburn damage. An- other advantage in reducing dense foliage is that it lowers the risk of insect infestations and disease.

Old trees can be rejuvenated by cutting back to either the scaffold branches near to the trunk or to the main trunk itself. In old groves a cycle of heavy pruning over 6-8 years will result in the development of "young" healthy trees bearing commercial quantities of olives. Grafting on new varieties is also possible with such radical pruning procedures.

Research needs to be undertaken to develop and evaluate machine assisted pruning methods.

Fertilisation

Both in Australia and in Europe applications of superphosphate, nitrogen, potassium, animal manures and mulching agents have a positive effect on the yield of olive trees. Nitrogen is the most important nutrient being required for new shoot growth and flower set. Soil and leaf analysis can be used to guide the fertilisation process. A typical application for mature trees is about 4 kg of 17:7:9 NPK. For dryland groves 75% is applied any time between April and July with the balance in spring. With irrigated groves, the nitrogen can be divided into three applications, 50% in April and 25% each in January and September. If required, phosphate and potassium are generally applied in spring at rates per tree of up to 0.5 kg for phosphorous and 1 kg for potassium. In Australia 3-5 yearly applications of superphosphate are usually sufficient. Foliar sprays of urea and boron are also useful.

Diseases, Infestations and Pests

There appear to be less problems with disease in olive trees growing in Australia than in Europe. This could be a function of the low levels of olive activity in Australia and the strict national and international quarantine controls that are practised. Even so scale infestations, black scale (Saissetia oleae) and olive scale (Parlaturia oleae), parasitise the carbohydrate supply of olives reducing the sugar content and increasing the acidity of fruit. Infected trees have visible scale and fungus, the latter growing on the honeydew excreted by the scale. Fruits are deformed and leaf drop occurs. Olive lace bug (Froggattia olivinia) also extracts carbohydrates from the leaves and hence debilitates the tree.

Another common pest is the nocturnally destructive black vine beetle which lives in the soil during the day and moves onto the olive leaves at night. Evidence of its effect is the characteristic chewed margins of the leaves.

Fungal infestations can destroy total olive crops. Although not as widespread as scale, anthracnose (Gloeosporium olivarum) infection is most destructive. Infection sets into young fruit and evidence of the disease is not apparent until the fruit ripens where soft rot develops from the sides and tips of the fruit. Olive leaf spot or peacock spot caused by the fungus Spilocea oleaginea is less common in Australia. Signs include dark round lesions on leaves causing premature leaf drop and damage to young wood. Productivity of affected olive trees is reduced. Other fungi such as Verticillium and Phythopthora can be devastating to olive trees.

Bacterial and nematode infections are not a major problem at this point of time in Australian olive groves. Birds and animals are a problem particularly where natural food sources have been lost to development and agricultural activities. A variety of birds damage or eat the olives, damage young shoots and hence reduce productivity. Land-grazing animals, indigenous, feral or farmed can cause physical damage, eat the growing shoots and ringbark the olive trees.

Orchard hygiene and careful attention underlie the management of all the above problems. Ensuring clean surrounds, removal of damaged fruit that can harbour infection and removal of diseased parts of plants is the basis of disease control. Mulching with straw and ensuring branches do not have contact with the ground is vitally important. A second strategy is the application of appropriate 'cidal' agents. Here care must be taken that the agents have been approved for use in olives. More research needs to be undertaken to determine herbicide and pesticide residue levels in olive fruit and olive oil. When using sprays there is always the risk that natural predators may also be killed causing further unexpected problems.

Olive Harvesting

Traditionally olives have been picked by hand. With increasing labour costs, methods such as machine harvesting with tree shakers, suitable for most cultivars has become popular. Hand picking is adequate for small groves, however proves to be impractical and too expensive in commercial groves. A major advantage of hand-picking is that the fruit is less likely to bruise resulting in better presentation for the fresh fruit and table olive market. For ma- chine harvesting, olives must be of a weight that it will dislodge on shaking. The Koroneiki olive cultivar originating from Greece, produces one of the best commercially available extra virgin oils, however it is too small (1-2 grams) to pick with a tree shaker. New growing methods with olive trees as hedge-rows and picking technologies similar to those used for grape picking need to be perfected to allow for more efficient olive production. Bruised olives and olives that have fallen naturally from trees are likely to produce oils that will not meet the olive oil purity and quality tests such as free acid and organoleptic tests because of increased likelihood of fermentation.

Olive cultivar selection is not only important for harvesting method but also in relation to fruit maturation. Cultivars will mature at different times during the season, which can be advantageous for hand picking, however when the groves are to be picked over a relative small period of time then an appropriate maturation index needs to be determined. A rule of thumb method is to pick when the crop characteristics are about one quarter green ripe, one quarter are black ripe and the reminder of the crop is half ripe. Green ripe olives will produce a green fruity oil whereas black ripe olives yield a yellow sweeter oil.

Depending on the cultivar and degree of ripeness, olives are picked between autumn and spring. Table olives are picked in the early to mid part of the period whereas oil olives can be picked in a later part of the period.

Post Harvest Handling

Olives should be processed as soon as possible and certainly within 3-4 days after picking. Processing within the grove facilities, particularly for table olive production is ideal and should be part of a vertical integration plan. If the grower also produces the oil profitability increases markedly. Olives must be handled carefully after picking because of their low bruising resistance. Olives should not be left standing around in bags, stacks or in trailers because of the risk of fermentation and the development of off flavours. Storage life of olives at 20°-30° C is only a few days after harvest, however storage life increases when they are stored in a cold room. Olives are very sensitive to deep freezing, temperatures, -15° to -5° C, however more research needs to be undertaken as to the quality of oil from thawed olives and the cost effectiveness of the process.

Uses of Olives

Foodstuffs

Olive fruit is a source of important foodstuffs, preserved table olives and olive oil. Table olives are popular as part of the Mediterranean diet and more recently an integral part of the take away pizza market. The latter has been a major market for preserved olives in the United States of America. To make olives edible the fruit flesh is modified by fermentation, salt treatment or drying to remove the bitterness due to polyphenolic compounds and in particular oleuropin. No toxicity to the fruit is known, however poorly preserved fruit can result in food poisoning such as botulism. Olive fruits are rich in oil and therefore high in energy. They are a good source of protein and β-carotene and contain other useful nutrients such as sugars, Vitamins B, C and E, Iron and other minerals.

Consumer forms of preserved olives are pickled green or black. Those prepared by the Spanish method are stored in salt solution whereas Greek style olives can have vinegar and added olive oil. Most commercially available black olives are artificially coloured during processing using sodium hydroxide and iron salts. Dried black olives and taponade are also popular and can be easily prepared domestically and commercially. The latter is a paste containing preserved olive flesh, anchovies and capers. Every country that is in the olive business believes that their olives are the best!

Olive Oil

Olive oil is obtained by pressing or centrifuging the crushed fruit including the seed. All olive oils obtained from olives are classified as Virgin Olive Oils with the highest quality being Extra Virgin Olive Oil. This has an acid value of less than 1 % and an organoleptic rating of greater than 6.5. Olive oils marketed as pure olive oil, although very popular with consumers, are generally poorer in quality than Virgin Olive Oils. They are processed from poor quality olive oil to remove impurities and off flavours. Olive Pomace Oil is made up of solvent extracted oil from the pomace remaining after pressing the crushed olives for Virgin Olive Oil production. Olive oils, particularly the virgin olive oils. are high in monounsaturated fats, Vitamin E, polyphenols and aromatic compounds. The price of olive oil has fluctuated aver the past few years, but there is a general upward trend.

Margarine containing 30% olive oil is now available in Australia. Although Australian growers have claimed that they will aim for the virgin olive oil market, this will only account for 25-30% of the Australian olive oil. The bulk of the olive oil will need to be directed to the supermarket shelf and to the food services industry. This will necessitate the development of olive oil refining facilities capable of producing consumer acceptable olive oil from lesser quality olive oils.

Animal Feed

The fruit, leaves, and pomace are valuable as supplementary feed for animals, goats, sheep, fowl and others.

More research is required to develop technologies to improve the feed value from parts of the olive tree. Animals can forage under the trees eating olives that have fallen to the ground. Olive pomace spread around the orchard also provides food for forage. The latter has value because of the protein and residual oil content. A problem in using pomace is that the crushed fruit contains both flesh and the poorly digestible woody pit. Current international research is focused around improving the availability of the fatty acids and breaking down the woody pit to improve digestibility. Animals find the olive leaves palatable and have no aversion to eating them from prunings and parts of the tree that can be easily reached. Methods for improving the nitrogen content of olive leaves are being investigated.

Compost and Fuel

Olive waste products have the potential for making compost or using them as mulching agents. Traditionally the pomace from oil making is spread around the grove providing valuable organic matter. Having the oil making facilities at the grove site allows the grower to take advantage of this valuable waste product. Where oil-making is associated with a larger centralised operation, the olive pomace needs to be disposed of in an environmentally acceptable manner. One process involves the solvent extraction of residual oil from the pomace, about 5%, which is then used to make olive pomace oil or used for technical grade oil for industrial or consumer directed products such as soaps. The olive pomace can also be incorporated into garden products by commercial compost producers. Because of its significant oil content, the pomace can be used as a fuel in the olive oil making plant or be pressed into blocks for commercial sale.

Farm Site Uses

The olive tree is a valuable shade tree for stock and for growing substory crops. Traditional broadacre farmers are seriously considering using olive trees as windbreaks and in alley farming practice. The olive tree will be a valuable landcare alternative to eucalyptus and other indigenous species. Being a long lived perennial, relatively deep-rooted under rainfed conditions, it will improve soil integrity and reduce soil erosion with the added advantage of providing a potentially saleable crop.

DATE: November 1999

* * * * * * * * * * * * *