USEFUL PALMS OF THE BORASSOIDEAE FAMILY: BORASSUS AND HYPHAENE

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Borassus and Hyphaene species

FAMILY: Borassoideae

These palms belong to the family Borassoideae - the Palmyra Palms - and a brief description of the family features (Whitmore, 1977) is given below.

Palms of this family are found in Africa and Asia and comprise 6 genera and 20-40 species.

BORASSUS

Commonly known as the Palmyra Palm in India and Ceylon, or Lontar in Indonesia, the genus comprises four accepted species (Uhl and Dransfield, 1987), two of which, B. flabellifer L. and B. aethiopum Mart., are widely-distributed and important economic plants. A third species, B. sundaicus Becc, has a limited use in eastern Indonesia where it is grown as a commercial crop in dry, poor, agricultural soil, where it is used to reclaim otherwise non-arable land (Baskoro, 1984).

According to some authorities the taxonomic distinction between B. flabellifer L. and B. aethiopicium Mart is tenuous in the extreme and, based on their relative economic uses and capabilities, Burkill (1966) considers them identical.

In the same way this author suggests that B. sundaica Becc., from Malaysia, should not be distinguished as taxonomically distinct from B. flabellifer. Whitmore (1977) also describes from Malaya a closely related genus Borassodendron which grows to 25 feet and has a large, untidy crown of dark, shiny leaves. The genus is characterised by the presence of flanges which penetrate towards the centre of the fruit from the stoney wall, reminiscent of the deeply-lobed coconut Lodoicea.

B. flabellifer L. is distributed in many tropical countries, but reaches its zenith, both as a conspicuous feature of the landscape and as a commercially important crop, in India, where it is found in great groves on the coastline from Bombay to Madras. To the east it is found in the dry areas of Burma and extends down the Thai peninsular until it reaches Kedah in Malaya. Further south in Malaya the climate is too wet and these palms can only be maintained by cultivation (Burkill, 1966).

In India, Borassus is a very important palm, and it has been estimated that as many as 40 million palms may be growing in Tamil Nadu State alone (Davis and Johnson, 1987), making it one of the most common trees in India, ranking second only to the coconut palm. Blatter (1926) offers an extensive account of its uses in India and quotes an ancient Indian poem, which lists no fewer than 801 different uses for the palm, and indicates that this palm has been deeply involved in the prehistory, literature, and folklore of India since the earliest period of civilisation on that subcontinent.

For instance, it has been suggested that the earliest form of Sanskrit writing was made on palm leaves some 6000 years ago (Ferguson, 1888). Further, the origin of the English terms 'leaf' and 'folio' in relation to book printing are probably derived from palm leaves writing (Davis and Johnson, 1987). Apart from the usefulness of the palm leaves as thatching material and for wrapping, the main economic attributes of Borassus palm are its food products such as fruits, nuts and palm hearts; in the extraction of sap for conversion into Toddy and/or Palm Sugar; its timber and its fibres. Each of these features will be discussed below.

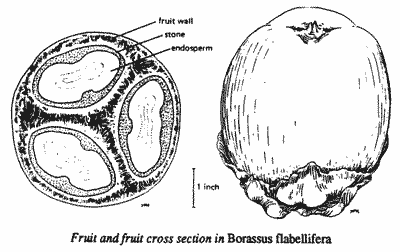

Mature palms produce 200-300 spherical fruits each year, each measuring 15-20 cm in diameter and each weighing, on average, 1.5 kg. Immature fruits are green but later become dark-purple to almost black (Davis and Johnson, 1987). Immature fruit are removed when the endosperm is still soft, sweet and gelatinous and sold in the marketplace. The fruit are sliced and the jelly-like endosperm is eaten, either raw or it maybe sliced and served in syrup. Mature fruits develop a fibrous, yellow mesocarp which can be eaten raw or baked, often being mixed with sugar. Each fruit bears three nuts, in which the mature endosperm is hard and bony and has no direct human use. However, germinating seeds develop a starchy, edible tuber. Davis and Johnson (1987) describe the process thus:

These authors make the pertinent point that starch obtained from these tubers may offer a commercial source for the production of industrial alcohol, though they caution against the widespread consumption of the starch, as preliminary toxological studies have shown it to possess both a hepatoxic and neurotoxic effect upon experimental animals.

'Palm hearts', i.e. the succulent growing points of the palm, are edible but it is suggested (Davis and Johnson, 1987) that they are unlikely to be an important nutritive source, and, of course, removal of the growing tips destroys the palm, making the harvesting of 'hearts' commercially untenable, except in areas where palms are being removed for land-clearing or some other purpose.

Perhaps the most valuable commercial product of the Palmyra palm is its sap, which can be drunk fresh or allowed to ferment into 'palm toddy' or 'palm wine'. The sweet sap is also the source of 'palm sugar' which itself is a valuable source of carbohydrate for further fermentation into alcohol and/or vinegar. Although methods of obtaining palm sap vary from country to country, the overall practice is basically similar. The tapper climbs the trunk of the palm and removes the terminal leaves to expose the young inflorescence. Regardless of whether the tree is male or female, the inflorescence axis is beaten with a wooden stave. It is said that in Tamil Nadu State in India, female inflorescences yield a larger quantity of sap.

The bruised inflorescence is then cut and the exuding sap allowed to drip into a container, and in some areas, a fresh cut in the inflorescence is made later in the day to yield more sap. The collected sap is taken directly to toddy shops, where it is sold and drunk immediately. However, naturally-occurring yeasts in the sap bring about rapid fermentation, and by the time it reaches the consumer it has an alcohol content of about 5-6%; this is referred to as palm 'toddy'.

Fermentation can be prevented by the addition of lime (calcium hydroxide) to the collection vessel. It is said that in Tamil Nadu a single palm can yield up to 150 litres of sap annually, and the cut inflorescences produce sap for 3-5 months (Davis and Johnson, 1987). In Burma, palm sap is collected in a similar manner, but here the actual method of collection, by means of ancient-style equipment, testifies to the antiquity of the practice, particularly in remote villages (Friedberg, 1977). Analysis of palm sap varies little from country to country; it contains approximately 15% sucrose with a pH of 6.4-6.9 (Franke, 1977; Friedberg, 1977). The most complete analysis of sap has been provided by Davis and Johnson (1987), based on the work of Paulas and Muthukrishnan (1983) and this is reproduced below.

Palm sugar, known also as jaggery in many parts of the East, is produced locally by allowing the filtered sap to boil in square containers until it thickens, and it is then poured into half shells of coconut to set. The resultant 'cake' is deliquescent because of the presence of salts in the sap, and in order to keep the 'cakes' dry they are either rolled in flour or else rice-flour is added to the boiling, thickening sap (Burkill, 1966). Palm sugar is also made on a commercial scale, but the sap is first slaked with lime and supplemented with either phosphoric acid or superphosphate (Davis and Johnson, 1987).

Two commercially viable 'spin-offs' from the production of palm sap are vinegar and alcohol. Vinegar production occurs naturally when palm sap is allowed to ferment anaerobically, and is the basis of many local industries. The potential value of commercially produced alcohol, however, is only now being realised, and an exploratory investigation by Jeyaseelan and Seevaratnam (1986) has recently explored the commercial viability of utilising palm sap to produce both alcohol and a secondary source.

| Composition of Palmyra Sap | |

|---|---|

| Specific gravity | 1.07 |

| pH | 6.7-6.9 |

| Nitrogen | 0.056 g/100cc |

| Protein | 0.35 g/100cc |

| Total sugar | 10.93 g/100cc |

| Reduced sugar | 0.96 g/100cc |

| Minerals as ash | 0.54 g/100cc |

| Calcium | Trace |

| Phosphorus | .14 g/100cc |

| Iron | 0.4 g/100cc |

| Vitamin C | 3.25 g/100cc |

| Vitamin B1 | 3.9 IU |

| Vitamin B complex | Negligible |

Results indicated that by careful selection, strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (the wine yeast) could carry out the fermentation process on crude sap to yield high levels of alcohol and a yeast biomass that was higher in levels of essential amino acids and protein than conventionally grown yeasts (Candida utilis) grown on molasses. Studies on animal nutrition confirmed this. Such work offers a new biotechnology to many regions of Asia where toddy drinking is discouraged, and where natural yeasts could bring innovative methods of commerce to even the most primitive areas where palms are grown and tapped.

Two other commercially useful byproducts of Palmyra palm are fibres and timber, and Burkill (1966) lists five separate kinds of fibres produced by a single palm: a loose fibre from the base of the leaf stalk; a long fibre from the leaf stalk; a fibre from the interior of the stem; a fibre or coir derived from the pericarp; and the fibrous material of the leaves.

Local usages of the various fibres produce beautiful local basketware, cord, rope, and matting. The leaf-base fibre is the raw material for the production of brushes, and this type of fibre is an important export commodity from various regions of India. Exact chemical and physical analyses of Palmyra fibres have been provided by Venngopal, Satyanarayana and Lalithambika (1984), who showed that these fibres have 41-49% cellulose and 28-43% lignin as their major constituents; while the mechanical strength of such fibres has been investigated by Satyanarayana et al. (1986).

Palmyra palm yields the only available timber in parts of India, and although the outer part of the trunk yields very hard wood, this portion is only a few inches thick (Burkill, 1966). This author also states that the male palm wood is harder and stronger than the female. An 85-year-old palm can provide a stem some 20 m tall, and the strongest wood is said to occur in the lowermost 3m from the base, while the uppermost section of some 8m cannot be used as timber and is sold as firewood (Davis and Johnson 1987).

Hyphaene

Commonly referred to as the Doum Palm or Dum Nut Palm, the genus comprises some 30 species distributed in Africa, Madagascar, and Arabia (Willis, 1966). Important economic species also occur in India and other parts of Asia, though considerable controversy ensues among taxonomists regarding the exact speciation within the genus. It was generally thought that the genus was endemic to Africa and that species occurring in Asia were acclimatised imports. However, a recent study by Furtado (1970) suggests that the common epithet Hyphaene thebaica described from Israel and Ceylon should be renamed H. sinartica and H. taprobanica respectively. A third well known species, H. indica, from the North West coast of India, should be renamed H. dichotoma, while a fourth species, H. reptans, has been recorded from the mountains of Arabia. Notwithstanding these new taxonomic developments the major species described in this paper is Hyphaene thebaica L. Mart. - the common Doum Palm of Egypt. Another species, H. natalensis, the Lala (or Llala) Palm from Tongaland in Natal province is also mentioned as a source of wine.

Hyphaene is botanically interesting as it is the only genus of Palms in which the trunk branches above ground. The most well known species, H. thebaica, has a long history of cultivation in Egypt as far back as 1800 B.C. and is now an economically useful plant in many arid regions of the world. The following account of H. thebaica is a composite based on the descriptions by Purseglove (1975) and Whitmore (1977).

Analyses of the chemical composition of kernels has been made by Amin and Paleologou (1973) who showed it consisted of. 11.3% oils; 7.0% protein; 1.72% ash; 11.76% moisture; 37.2% cellulose; and 30% mannans. The most important commercially exploitable component of the kernel is the sugar D-mannose, and extraction of this component was achieved following acid hydrolysis (Sallem, 1977), resulting in a 20% overall yield. Analysis of the woody endocarp was also investigated and this was found to consist of 23% xylan and 52.3% cellulose. Following methylation of the B-linked xylan, the degradation products confirmed the presence of 1-4 linkages in the chain, and that C-3 was the point of branching in the molecule.

Pesce (1985) has further suggested that the nanocellulose found in the seeds can be transformed into glucose mannose, which in turn can be fermented by means of yeasts into alcohol. Transformation into cellulose can be achieved either by 5% hydrochloric acid or by the involvement of diastase extracted from germinating palm seeds.

As with many tropical fruits which constitute at least a portion of man's diet, investigations into their pharmacological properties appears to be a never-ending source of study for physiologists. When investigated chemically by Sharaf et al (1972) the fruits of Hyphaene proved to:

In another investigation, Amin and Paleologou (1973) demonstrated that both the nut kernels and pollen grains of H. thebaica contained the animal hormone estrone, through the significance of the discovery was not discussed.

The other well-established species of Hyphaene is the Lala (or Llala) Palm of South Africa. This species is now recognised as H. natalensis Kunze, though it was formally known as H. crinita (Furtado, 1970). At present, the Lala Palm occupied an area of approximately 156,000 ha in Tongaland and Northern Zululand, and the total number of individual palms is estimated at about 10.5 million.

Moll (1972), in an outline scheme to utilise the leaves for commercial fibre, estimates that with adequate management it is possible to collect some 33 million leaves annually. This writer also explores the commercial exploitation of the sap of these palms, which when allowed to ferment yields a potent drink known locally as ubusulu, which, because of the involvement of yeasts in' the fermentation process, provides essential Vitamin B, riboflavine and nicotinic acid in the diet of the local Bantu tribes.

In a detailed investigation into the chemical composition of the fermented sap, Nash and Bornman (1973) offer the following information. The viscous sap had a pH of 6.3 to 6.8 and the only reducing sugar detected was glucose. Following filtration of the fermenting yeast cells, thiamine and nicotinic acid were detected, along with 2% ethyl alcohol and the amino acids indicated in the table.

The authors concluded that palm wine was a useful dietary supplement, supplying essential iron, nitrogen and sugars. They further suggested that the wine may acquire a higher nutritive value after a period of ageing, when yeast cells have autolysed and released their contents.

In discussing the growth characteristics of the various species of Hyphaene one immediately runs into difficulties. For example, H. ventricosa is referred to as a species with "bulging trunks" (Bailey, 1976) while Meninger (1977) refers to H. ventricosa as the Gingerbread Palm or Doum Palm and appends the following description from the Victoria Falls area of southern Africa:

|

"HYPHAENE VENTRICOSA PALM"

Native Name: Mulalaj Popular Name: Vegetable Ivory Palm This beautiful Palm Tree grows principally on the islands and banks of the Zambesi River, in the vicinity of the Victoria Falls. The Palm attains a height of 60 feet or more.

The fruit is the shape and size of a small orange. It is covered on the outside by a thin shiny brown skin. Beneath this is a thicker layer of fibrous nature which forms a popular diet for elephants, monkeys and baboons. This portion of the fruit is also edible to humans. A third, very hard, fibrous layer encases the kernel, which is inedible, extremely hard, and is extensively used in the manufacture of curios. Until the advent of plastics, Vegetable Ivory was used for the manufacture of studs, buttons, etc."

Another important species appears to be the Indian Doum Palm, H. indica Beccari, which is characterised by frequent dichotomous branching of the stem (Oza, 1974). Remarking on the distribution of this species, Meher-Homje (1970) notes: "The endemic occurrence of the species in the erstwhile Portuguese territories is a noteworthy feature ..... H. indica seems to be a case of early introduction on the west coast of India".

Doum Palms are said to be easy to cultivate, and the plants thrive in protected places in, for example, Southern Florida (McCurrach, 1960) . The photograph on page 105 of McCurrach's book Palms of the World shows a heavy crop of fruit in southern Florida - this hopefully might serve as a stimulus for wider planting of this palm.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

REFERENCES

AMIN, E.S. and Paleologou, A.M. (1973). A study of the polysaccharides of the kernel and endocarp of the fruit of the Down palm (Hyphaene thebaica). Carbohyd Res, 28 (2): 447-450.

BASKORO, J.B. (1984). Lontar Palm (Borassus sundaicus Becc.) Bulletin Kebun Raya - Botanical gardens of Indonesia 6(5): 119-126.

BLATTER, E. (1926). The Palms of British India and Ceylon. London.

BURKILL, I.H. (1966). A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2 vols.

DAVIS, LA. and Johnson, D.V. (1987). Current utilization and further development of the palmyra palm (Borassus flabellifer L. Arecaceae) in Tamil Nadu State, India. Economic botany, 41(2) 247- 266.

FERGUSON, W. (1888). Description of the palmyrah palm of Ceylon. Observer Press, Colombo.

FRANKE, G. (1977). Borassus spp. and other sugar palms. Karl Marx University, Leipzig, German Democratic Republic, 15(3): 249-256.

FRIEDBERG, C. (1977). Sugar and wine palms in Southeast Asia and Indonesia. Journal Agriculture Traditionelle et de Botanique Appliquee, 24(4): 341-345.

FURTADO C. X. (1970) . Asian Species of Hyphaene. Gard.Bull.(Singapore),25(2): 299-309.

JEYASEELAN, K. and Seevaratnam, S. (1986). Ethanol and biomass from Palmyra palm sap. Biotechnology letters, 8(5): 357-360.

McCURRACH, J.C. (1960). Palms of the world. Harper and Brothers, New York, pp.290.26.

MEHR-HONIJI, V.M. (1970). Notes on some peculiar cases of phytogeographic distributions. Journal Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 67:761-763. 27.

MENNINGER, E.A. (1977). Edible nuts of the world. Horticultural Books Inc. Florida, pp.175.

MOLL, E. J. (1972) The distribution, abundance and utilization of the lala palm, Hyphaene natalensis, in Tongaland, Natal. Bothalia, 10(4): 627-635.

NASH, L.J. and Bornman, C.H. Constituents of Llala wine. Hyphaene natalensis. S.Afr.J. Sci, 69(3):89-90.

OZA, G.M. (1974). Indian doum palm faces extinction. Hyphaene indica. Biol Conserv. 6(1): 65-67.

PAULAS, D. and Muthukrishnan C.R. (1983). Products from Palmyrah Palm. Paper presented to FAO/DANIDA workshop, Jaffna, Sri Lanka.

PESCE, C. (1985). Oil palms and other oil seeds of the Amazon. Reference Publications Inc., Michigan, pp.199.

PURSEGLOVE, J.W.(1975). Tropical Crops: Monocotyledons. Eng. Lang. Book Soc. and Longman, London pp.607.

SALLAM, M.A.E. (1977). Preparation of D-mannose from doum-palm kernels. Carbohydrate research 53: 134-135.

SATYANARAYANA, K.G.; Ravikumar K.K.; Sukumaran, K.; Mukherjee, P.S.; Pillai, S.G.K. and Kulkarni, A.G. (1986). Structure and properties of some vegetable fibres. Journal of Materials Science, 21: 57-63.

SHARAF, A.; Sorour A; Gomaa, N. and Youssef M. (1972). Some pharmacological studies on Hyphaene thebaica Mart. fruits. Qual. Plant Mater. Veg. XXII, 1: 83-90.

UHL, N.W. and Dransfield, J. (1987). Genera Palmarum, a classification of the palms based on the work of Harold E. Moore Jr. The International Palm Society, Kansas. (in press).

VENUGOPAL, B.; Satyanarayana, K.G. and Latitham-bika, M. (1984). Chemical characterization of some vegetable fibres. Res. Ind., 29(4): 273- 276.

WHITMORE, T. C. (1977). Palms of Malaya. Oxford University Press, pp. 132.

WILLIS, J.C. (1966). A dictionary of the flowering plants and ferns. 7th Ed. Cambridge University Press, pp.1245; 1-LXVI.

******************

Extracted from D.A. Griffiths' forthcoming book, Palms of Economic Value, to be published by Cornucopia Press, Subiaco, Australia

DATE: January 1991

* * * * * * * * * * * * *