POMEGRANATE CULTURE IN CENTRAL ASIA

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Punica granatum

FAMILY: Punicaceae

Introduction

The pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) is the only species in the genus Punica, and appears to be a relict of a much wider Mediterranean distribution of clear Gondwanan origin. The family has every indication of a tropical origin, but has evolved under natural selection and domestication, with the latter extending its range well beyond its native area.

Cultivation and selection has produced many cultivars, reflecting the internal polymorphism of the species. Within the former USSR, the pomegranate is native to Central Asia and the Caucasus, but in this area, vegetative propagation has been common and a number of interesting local forms have been preserved. N.I. Vavilov, after whom our Institute was named, showed great interest in the pomegranate. In a letter to A.D. Skrebskova he mentioned how much he liked the fruit, and suggested that the time was right to elucidate and describe the evolutionary path it had taken [Vavilov, 1987a]. In other letters to her he expressed the need to investigate pomegranate polymorphism and cytology, to extend its cultural range [Vavilov, 1987b], and to preserve its natural geneplasm resources [Vavilov, 1965].

The Plant

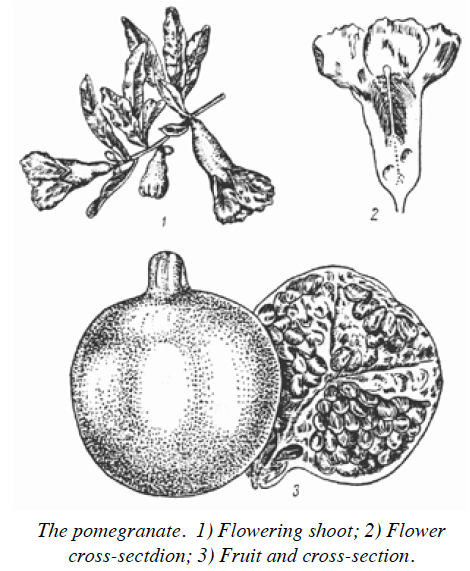

The pomegranate has the form of a shrub, 1.5-3m high, with perhaps 20-40 stems of varying age and diameter. Rozanov [1961] has noted a 5m plant. This had stems up to 6cm across, with dingy-grey, finely-fissured bark. Popov [1929] considered that pomegranates of the Pamir-Altai district were distinctive for their brownish-yellow stems, and on this basis classed them under the form tadshikorum.

Young pomegranate shoots are greenish-grey and spiny, one-year wood is yellowish green and bare but ends with a needle-like prickle. Buds are small (0.2cm), brownish-green, and turnip-shaped. Leaves on one-year wood are opposite-paired, on two-year wood they appear as leaf bundles, 3.8-4.0cm long and 1.3-1.6cm wide. They are broad-lanceolate with entire margins, narrowly wedge-shaped at the base, roundish at the top and always bare and shiny. Petioles are 0.7-0.8cm long, and bare.

Time of leafing-out depends on the local conditions, so that along the Piandzh River and on well-warmed southern slopes at 600-700m elevation, leaves appear as early as March. At the upper limits of its range, as in Pamir-Altai at an altitude of 1200-1300m, leaf-out starts in the first half of April and growth ceases in June. On the other hand, in the irrigated areas of the Gissar valley, pomegranates continue growth into late autumn.

In the wild, a period of intense growth precedes flowering. In Pamir-Altai pomegranates lose their leaves with winter, but in warmer areas such as Florida and South China, they may be evergreen. Rozanov [1961] considers that leaf-shed is an adaption to a dryer, more temperate climate.

Flowers appear in leaf axils of current-year shoots, they may be perfect, or more often single sex, and have 7-8 crimson petals. The style is single, with a lobed stigma. Flowers may be large, jug-shaped, with well-developed ovary and style - 'long-pistilled'. The smaller, 'short-pistilled' flowers are bell shaped, with many developed stamens but an underdeveloped ovary.

Pomegranates are in flower from May till August, one flower lasting 2-3 days. The long-pistilled flowers open first, the short-pistilled ones follow 7-8 days later. In late May to early June the short-pistilled flowers drop, but the long-pistilled ones carry through. Late flowers lead to under-developed fruits. When in flower, pomegranates look very showy.

The Fruit

Pomegranate plants bear a distinctive, specialized berry-type fruit called a cenocarpium, with many seeds surrounded by juicy flesh and in a unique two-storied arrangement called a nidus, within a distinctive tough, pliable rind. Fruits of wild pomegranates are very varied, but are usually roughly spherical, somewhat flattened at the top, smooth, of a washed-out greenish- or orange-yellow colour. Some wild fruits are dingy green. The pulp is pink and sour, or very occasionally sour-sweet. Cultivated varieties are even more varied in shape and colour, the latter ranging from pink and crimson-red to blackish-violet and blue [Petrova, 1989].

According to B.S. Rozanov [1960, 1961], fruit characteristics can be used to distinguish two subspecies, Punica granatum subsp. chlorocarpa, which includes all wild forms and some cultivated forms, and P. granatum subsp. porphyrocarpa, which includes only some cultivated forms.

Fruits ripen in September and October. From a single shrub growing in the Darvaz Mountains, 100-200 fruits may be obtained, but their size and weight will vary greatly with conditions - drier conditions means smaller fruits. Wild plants growing along river banks or on well-exposed slopes may give fruits as good as orchard plants; the main difference then is in the size and flavour of the fruits. Generally, wild fruits are smaller and more sour than orchard fruits [Vavilov, 1929; Speranskii, 1936; Neubauer, 1954; Evreinoff, 1957].

Rozanov has shown that Tadzhikistan cultivars, such as 'Chuchuk-dona', 'Shaarsabzy', 'Oblik-Nardon' , and 'Achik-Anor', are the closest to wild forms, and represent the first stages of domestication. Many cultivars found in the Darvaz, Gissar, and Karategin Mountains were originally selected from the wild, and have restricted areas of use, as little as one village. Evreinoff [1957] has pointed out that the pomegranate represents a classical example of domestication of a wild fruit tree. Introduction into culture did not occur at any one centre, but was a parallel process extending over the whole wild range. As with Central Asia, other countries within the natural range, such as Afghanistan and Iran, have their own local selections.

Pomegranate seeds are very small, with 250-300 seeds per fruit, and light brown. They germinate easily. Their composition is 6-35% water, 6-21% fat, 12-20% starch, 22-34% cellulose, 9-10% nitrogenous compounds, and 1-2% ash. Some specimens have high seed oil content, including punic, lauric, palmitic, arachic, and linoleic oils. They may also have a high content of tocopherol, a natural auto-antimutagene. This may be one reason why this relict genus has persisted. There is no tocopherol in the vegetative organs, which may have a link to the increase in somatic variation in the north of the natural range.

Reproduction and Growth

In the wild, pomegranates reproduce by seed. Seedlings appear in April. Growth is slow at first, especially in dry conditions, then speeds up somewhat. On dry slopes, a seedling may take 10-12 years to reach a height of 1m; if irrigated it may reach the same height in 2 years. The plants are long-lived. Berezhnoi [1951] has found plants as old as 50-70 years, while Kuznetsov [1956] noted pomegranates as much as 300 years old in the Surkhan-Darinskii region of Uzbekistan.

Pomegranate roots may reach a depth of 170cm after 4-6 years, and after 8-9 years their surface roots extend well beyond the canopy limits, and so may have a major role in anchoring mountain slopes and soils, with their drought-resistance a major plus.

Even though pomegranates have good drought resistance, they will grow well in soils of high moisture content. Plants grow successfully in areas where winter temperatures do not fall below -12°C, with long, hot summers, and a warm, dry, even autumn. If temperatures fall below -20°C, pomegranates may be killed back to the ground. Under conditions where the vegetative period is sufficiently long but temperatures may fall below -15°C, frost protection is needed for successful crops. Spring frosts are not usually a problem as the pomegranate is a late bloomer, but autumn frosts before harvest can be dangerous. Good fruit ripening needs a hot summer and a long, dry, and warm autumn.

Pomegranates will grow on rocky mountain slopes, on riverbank sands, and even on gravels and alkaline soils. Best growth is obtained on deep fertile well-drained loams and clay loams. Plants will not withstand very salty or marshy conditions.

The plants have been used as hedges and boundary plants in orchards since ancient times; sometimes there is no distinction between the hedge and the orchard plant. In the wild, pomegranates are found associated with Bokhara almond, hawthorn, pistachio, Regal maple, sumach, and other local trees. More rarely, and mainly along the banks of the Piandzh River, pomegranates are found in small groves with plane trees, persimmons, grapes, and figs, at springs. These groves are protected as sacred places by the local inhabitants [Zapriagaeva, 1947].

Uses

Pomegranate fruits, including wild ones, have a very wide variety of uses. Their most important product is pomegranate juice, essentially the contents of the gigantic sarcotestal cells which form the integument around the seeds. The juice contains 76-78% water, 1.1-1.5% protein, 8-21 % sugar, 1-3% fat, and 0.3-5% acids. Wild pomegranate juice contains much the same amount of sugar as that from cultivated types, but the acid content is more than double, which detracts from the taste. Juice may be used in fresh drinks, syrups, extracts, seasoning in meat dishes, as well as in confectionary and ice-cream. Juice of wild pomegranates can be used for producing citric acid crystals.

The rind of the fruit is no less valuable than the juice. Wild pomegranates have thicker, tougher rind, containing more tannin, than cultivated ones. Tannin content may be 26-30% Grossgeim, 1946; Sokolov, 1952], soluble matter up to 21.8%, gum 34.2%, and resin to 10.9%. Pomegranate tannins are used to treat the thinnest sorts of leather, including Morocco [Endin, 1944], and have also been used in dyeing cloth. Dark brown or beige colours are used with silk, green, khaki or browns with cottons, and yellow-greens in wool blends. Pomegranate rind has been locally used for centuries to get fast brown and black dyes.

Pomegranate rind extracts, containing substantial amounts of tannins, have been used medicinally to treat gastric disorders [Kushelevskii, 1891; Jayaweera, 1957; Parsa, 1960]. Alkaloids in the rind, especially pelleterine, have wide medical application. Extracts give a positive action with acute and chronic enterocolitis, and will usually cure diarrhea after 4 days [Rossiiskii, 1946]. Rind also contains isopeleterine, which is highly active against liver fluke [Wibaut, 1957]. Pomegranate bark from branches, trunks, and roots contains up to 32.7% tannins [Stankov, 1951], and root bark has been used as an effective vermifuge for many years in India, Britain, and European counties [Watt, 1892].

Ground pomegranate root is used in popular medicine to relieve injuries and fractures and reduce pain [Gammerman, 1957]. Watt [1892] notes it as the best remedy for chronic dysentery. Flower petals and buds also figure widely in folk medicine, with infusions used to stop bleeding [Abu-Ali Ibn-Sina, 1956], treat throat disorders [Medvedev, 1919] and dysentery [Watt, 1892], and as a febrifuge [Monteverde, 1927].

For the people of Central Asia, the pomegranate is a symbol of plenty, and a potent local medicine. Considered a sacred plant, the wood was not burned. In ancient times there was a considerable trade in pomegranate petals as a source of fast red dyes, but how these were prepared is not currently known. Pomegranate leaves have been used as a tea substitute [Sakhobiddinov, 1948]. Seeds have been used to prepare vinegar [Strebkova, 1931) and extract oils [Nesterenko, 1949], as well as a remedy for fever.

Although these days pomegranate is regarded mostly as a fruit-bearing plant, it can also serve as a beautiful ornamental. Especially valuable are forms with double flowers (P. granatum forma multiplex), with white flowers (f. albescens) and with yellow petals (f. flavescens) [Rehder, 1949].

Wild pomegranate ranges are found in the Transcaucasus, Asia Minor and Central Asia, Iran, and Afghanistan [Neubauer, 1954]. Within the former Soviet Union, disjunct ranges of wild pomegranate exist in the Transcaucasus [Voronov, 1925], Kopetdag [Popov, 1929], and Pamir-Altai [Zapriagaeva, 1964].

As regards Soviet pomegranate cultivation, this has been centred in the Central Asian republics, with about 3 million trees [Kolesnikov, 1973]. In Uzbekistan, pomegranate orchards are widespread in the Surkhandarin, Andizhan, Namangan, Fergan, and Bukhara regions. In Tadzhikistan, pomegranates are grown in the north and north-west, with the main area (74 %) being the Vakhsh Valley, with many new plantings - this area does not need frost protection measures.

In Turkmenistan, pomegranates are grown in two places, in the Ashkhabad region near the Maryi oasis, with winter protection, and in the south-west, on open ground. The most technically advanced plantings in Central Asia achieve yields of 15-20 tonnes of pomegranates per hectare.

Selection and Varieties

Breeding and selection of pomegranate varieties on a scientific basis has been going on for about 40 years - very little compared to perhaps 50 centuries of local folk selection. Scientific techniques used have included selection from open-pollinated seedlings, varietal crossings, selection of sports, and all manner of interbreeding, backcrossing, and hybridization approaches, including introgression to the F4 generation. So the new cultivars do not exceed 3 or 4 decades in age, compared to 2- 5 millennia of folk selection and 5- 7 million years of natural selection of the species.

The most important breeding achievements during the Soviet period have been: 1) deriving a suite of soft-seeded, sweet-acid cultivars; 2) obtaining compact-habit cultivars, intended for intensive cultivation in modified environments; 3) selecting soft-seeded cultivars which ripen early and extra-early, with the aim of extending the regions over which pomegranates may be grown. The following list includes the most important and widespread varieties.

1. Achik-Dona. An Uzbek selection. Fruits are large and spherical, with a pinky-gold skin. Seeds are large and long, the pulp is sweet and tasty. It produces high yields and ripens in mid to late October.

2. Bala-Miursel. A local Azerbaidzhan selection. Plants reach 3m in height. Fruits are large (400-500g), the rind is a deep crimson, and thick. Large-seeded, with red, sweet-acid juice, containing up to 16% sugar and 1.5% acids. Fruits ripen at the beginning of October and will keep for 3-4 months. Yield is 30-50kg per plant.

3. Giulosha Azerbaidzhan. Plants grow to 3m, fruits weigh 300-400g. Their skin is pinky red, thin, and shiny. Seeds are large, juice is bright pink and sweet-acid, containing about 20% sugar, 1.8% acids. Fruits ripen in early to mid October, and keep for 2-3 months.

4. Guilosha Pink. Another local Azerbaidzhani selection. Fruits are round, medium size (200-250gm), sometimes larger. Seeds are of medium size, juice yield is high (around 54%) and of excellent flavour. Sugar content is 15.6%, acids 1.3%.

5. Kazake-Anar. An Uzbek selection with large (300-400g) yellow-green fruits, medium thickness rind, and big seeds. Juice is crimson - red, sweet-acid and of good flavour, containing about 20% sugar and 1.85% acids. Juice yield is about 45%, this high-yielding cultivar ripens in the first half of October. A very widespread variety.

6. Kaim-Nar. An Azerbaidzhani variety with medium-size fruits (200-250g), greenish with a bright-red blush. The dark red juice is tasty and sweet-acid, fruits ripen mid-October.

7. Kai-Achik-Anar. An Uzbek-Tadzhik variety in which the plants grow quite large. Fruits are large (300-400g) and spherical, ripening in mid-October. They transport and keep well. Plants yield about 50kg each of fruit with 16% sugar, 1.4% acid.

8. Kzyl-Anar. An Uzbek variety with medium round fruits. Their shiny green skin is of average thickness. Seeds are medium size. Juice yield is about 54%, sweet-acid with 15% sugar and 2.2% acid. Fruits ripen in early to mid-October and keep for 4-5 months, but do not travel well.

9. Krmyzy-Kabukh. An Azerbaidzhani variety of exceptional quality. Plants are very tall (4 m), fruits are large (350-400g), bright red, and spherical. Medium rind, large seeds, yielding about 45% of red sweet-acid juice, with about 14.5% sugar, 2.1 % acids.

10. Nazik-Kabukh. An Azerbaidzhani selection which produces large (400g) dark red fruits on a tall (4m) plant. Fruits contain big seeds, yield about 49% sweet-acid juice, with about 12.3% sugar and 2.6% acids. Fruit ripens in early to mid October, keeps for 3-4 months, and is in high yield.

11. Shakh-Nar. An Azerbaidzhani selection growing on a small plant. The medium-size (300g) red fruits are round or pear-shaped, with average-thickness rind. Seeds are small, juice yield is around 50%, the sweet-acid juice has about 13.4% sugar and 2.1 % acids. Fruits are ripe in the second half of October, and keep for 6 months. Yields are good.

A great many other varieties exist as well as these. They include Surkh-Anor, Kavadany, Iridane, Ak-Dona, and Shirin-Nar.

Further Development

The present aim in Central Asia is to increase the area under pomegranate production, and 10 specialist plantations of this fruit have been established, but the range of varieties in use is still very limited. This limits the season of fruit availability and puts pressure on harvesting and processing processes. There is a need to develop early varieties suited for intensive culture.

However, in practice, breeding work has almost ceased. In Tadzhikistan, a small amount of variety crossing is still being carried out, working with the gene bank assembled by Prof. B. S. Rozanov and T. A. Ivanova, all directed to obtain dwarfed cultivars suited to artificial shelter and producing soft-seeded, sweet-acid fruits. In Azerbaidzhan, many cultivars and promising selections have emerged from the gene bank collection of A.D. Strebkova and Prof. L. M. Akhund-zade.

One of the largest assemblies of pomegranate resource material is that of the Vavilov Institute's Turkmen Experiment Station - this numbers more than 1000 selections. A small amount of work on soft-seeded cultivars is still being carried out there. The climatic conditions of the Station, in the north of the open (unsheltered) pomegranate culture belt, has enabled some good selection work to be carried out. For example, in the 1950-60 period, N.L Zaktreger was able to select a series of promising cultivars and forms.

Selections with early or extra-early ripening features are of special interest. For example, fruits of the test variety 'Super-early' ripen at the beginning of August. Soft-seeded varieties which ripen between late August and early September include '6/49' (selected by Prof. Rozanov) , and 'Andalib', 'Kerogly', 'Siunt', 'Zelili', 'Anvari', 'Sumbar', and 'Shikhimderinskii' (selected by Zaktreger). All these, according to G. M. Levin [1990], are promising for testing in the northern, colder regions of pomegranate culture.

The soft-seeded varieties are of excellent eating quality. This group contains about 100 accessions with a range of ripening and taste characteristics. Varieties which reached the official testing and registration stage included 'Podarok', 'Shainakskii', 'Agat', 'Gissarskii Alyi', 'Gissarskii Krupnoplodnyi', 'Meskheti', and 'Azerbaidzhan'.

Good cold and frost resistance is found in the 'Kazake' strains, most of which have valuable cultural and biological traits. The seedling '57/12' is notably cold-resistant. For the modified-environment areas, the dwarf, soft-seeded and sweet-acid selections of Rozanov and Ivanova are promising, especially the variety 'Agat'.

Propagation

Pomegranate is normally propagated from cuttings, occasionally by grafting. One-year or two-year wood is used, with cuttings 20-25cm long and at least 0.5cm across. They may be taken between December and mid-April, and may be stored in a cellar in damp sand, or buried in trenches in the open ground.

Cuttings are set out after cutting across under a lower node with a sharp knife. They should be inclined rather than upright, with one bud exposed, at a separation of 16-20cm within the row and 90cm between rows. They can be transplanted from the nursery when 1-2 years old and with shoots 40-50cm long.

If grafting is used, wild or semi-cultivated pomegranate rootstock is recommended. Best results are obtained with bark or whip-and-tongue grafts. Grafting is done in spring, budding is best done with dormant buds early in September.

Culture

Best spacing for pomegranates is still not decided. Layouts from 3 x 3m to 8 x 8m have been recommended. However, the most widely-accepted spacings are 4 x 2m or 4 x 3m, corresponding to 1250 and 833 plants/hectare.

Soil treatments are as for normal orchards. Ploughing each year to a depth of 20-25cm, depending on the root system, is normal. The best fertilization method is to apply 30-40 tonnes of animal manure per hectare every two years, corresponding to N120-P90-K60. Irrigation is very important to obtain good plant growth conditions and ripen good fruit, the amount required equates to 900-1000 cubic metres per hectare. Pomegranate plantations are irrigated about 12 times during the vegetative period, usually once in April, twice in May and June, 3 times in July and August, and once in September.

Pomegranates can be grown as a multi-stemmed shrub with 3 or 4 stems, or as a small tree with 4-5 scaffold branches. On each of these, 4-5 secondary shoots may be left, each with their own tertiary shoots, and so on. Unwanted suckers and shoots are cut out systematically. It is specially important to see that root suckers and watershoots are not left, these should be cleaned out 3 or 4 times a year.

Pomegranates bear both on older wood, especially that 2- 3 years old, as well as on current season growth. Best fruit yield and quality is obtained from older wood. Because of this, it is desirable during early pruning, before blossoming, to remove about 50% of current-year shoots, and shorten the remaining half so that flower buds do not form on them [Arendt, 1973].

These shoots are shortened again in late July-early August, while main pruning is done in autumn. The aim of this is to thin the crown, leaving the strongest and best-formed branches. Replacement of older (3-5 year) branches with new ones, plus timely removal of current year non-fruiting shoots, are major requirements to maintain regular high yields.

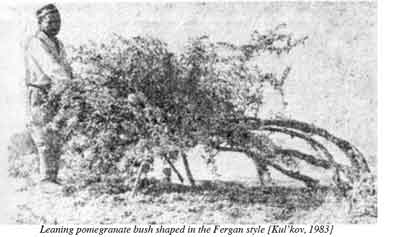

Under protected-culture conditions, it is more reasonable to form a leaning shrub with three main branches, to reduce breaking of branches and rotting when this is covered during winter. Shaping is commenced the second spring after planting. The aim in pruning is to attain precise and timely control of growth processes in the inclined branches to give optimum growth and fruiting. Correct pruning in protected culture can increase yields by at least 14%.

Fruit picking is an extended process, as all fruits do not ripen at the same time. The longer the fruits stay on the plant, the better their flavour and the higher their sugar content, so it is important to allow fruits to ripen on the tree as late as local climatic conditions allow.

References

Arendt, N.K. (1973): Introduction to Pomegranate Varieties (in Russian). Yalta.

Berezhnoi, I.M., et al. (1951): Subtropical Crops (in Russian). Selskhogiz, Moscow.

Endin, O.A. (1944): Dye plants of Turkmenia (in Russian). Trud. Turk. fil. AN SSSR, No.5.

Evreinoff, V.A. (1957): Contribution a l' etude du granadier. J. d'agric. trop. bot. appl. (Paris), Vol. 4 No. 3-4.

Gammerman, A.F., et al (1957): Medicinal Plants of the USSR (in Russian). In series Plant Resources of the USSR. vol.2. Moscow-Leningrad.

Grossgeim, A.A. (1946): Plant Resources of the Caucasus. (in Russian). Baku.

Ibn-Sina Abu-Ali (1956): Canon of Medical Science (in Russian).Vol.2. Tashkent.

Jayaweera, D.M. (1957): Indigenous and exotic drug plants in Ceylon. Trop. Agric. (Ceylon), Vol. 113, No 1.

Kolesnikov, V.A. (1973): Specialist Fruit Culture (in Russian). Kolos, Moscow.

Kul'kov, O.P. (1983): Pomegranate Culture in Uzbekistan (in Russian). Fan, Tashkent.

Kushelevskii, V.I. (1891): Medical Geography and Sanitation in the Fergan Valley (in Russian). Vol. 3. Novyi Margelan.

Kuznetsov, V.V., et al (1956): Pomegranate and Fig Culture (in Russian). Tashkent.

Levin, G.M. (1990): Pomegranate breeding (in Russian). Sadovodstvo i vinograd., No. 10.

Monteverde, N.A., and Gammerman, A.F. (1927): The Turkestan Collection of medicinal products, Museum of the Principal Botanic Gardens (in Russian). Izd. Glav. bot. sada SSSR, vol. 26, No.4.

Neubauer, H.P. (1954): Bemerkungen uber des Vorkommen wilder Obstsorten in Nuristan Angew. Bot. Vol. 28, No. 3/4.

Parsa, A. (1980): Medical plants and drugs of plant origin in Iran. Qual. pl. et mat. vegetab. Vol. 7 No.1.

Petrova, E.F. (1989): Subtropical Fruit Collection Studies (in Russian). Leningrad.

Popov, M.G. (1929): Wild fruits of Central Asia (in Russian). Tr. po prikl. bot., gen. isel. Vol. 22, No.3.

Render, A. (1949): Bibliography of Cultivated Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the Cooler Temperate Regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Jamaica Plain, Mass.

Rossiiskii, D.M. (1946): Medicinal actions of pomegranate fruits (in Russian). Farmatsiia, No.2.

Rozanov, B.S. (1960): Wild pomegranates of Tadzhikistan and their influence on cultivated selections (in Russian). Biul. nauch. info inst. sadovodstva AN Tadzh. SSSR, No.4.

Rozanov, B.S. (1961): Pomegranate Culture in the USSR (in Russian). Trud. Inst. sadovodstva AN Tadzh. SSR, Vol. 3.

Sakhobiddinov, S.S. (1948): Wild Medicinal Plants of Central Asia (in Russian). Gosizd. Uz. SSR, Tashkent.

Sokolov, V.S. (1952): Alkaloid Plants of the USSR (in Russian). AN SSSR, Moscow Leningrad.

Speranskii, V.G. (1936): Development of fruit culture and wild fruits in Tadzhikistan (in Russian). Trud. Tadzh.-Pamir. ekspeditsii, No.5. Stankov, S.S. (1951): Wild Fruit Resources of the USSR (in Russian). Nauka, Moscow.

Strebkova, A.D. (1931): The Pomegranate (in Russian). Tiflis.

Vavilov, N.L. and Bukinich, D.D. (1929): Agricultural Afghanistan (in Russian). Leningrad.

Vavilov, N.L (1965): Wild fruit resources of Kopetdag (in Russian). Rasten. Resursy, Vol. l, No.3.

Vavilov, N.L. (1987a): Scientific inheritance. In: Letters. 1929-1940. Vol, 10. Nauka, Moscow.

Vavilov, N.I. (1987b): Asia, source of species. In: Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants (in Russian). Nauka, Leningrad.

Voronov, Iu.N. (1929): Wild ancestors of fruit trees of the Caucasus and Central Asia (in Russian). Trudy po prikladnoi bot., gen., i sel., vol. 14, No.3.

Watt, G .A. (1892): Dictionary of the Economic Products of India. Vol. 5,6. London-Calcutta.

Zapriagaeva, V.L. (1947): Subtropical fruits of Darvaz (in Russian). Soobshch. Tadzh.filiala AN SSR, No. 2.

DATE: January 1994

* * * * * * * * * * * * *