BRAZENLY BEAUTIFUL TAMARILLO

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Cyphomandra betacea

FAMILY: Solanaceae

Although the term "tamarillo" is slowly becoming common usage in many countries of the world, the "tree tomato" is still a curiosity for many people. It is a native of Andean Peru and southern Brazil, but has become widely distributed throughout many temperate and subtropical areas. the tamarillo was acceptable to this foreign market. Investigations conducted in New Zealand on the horticultural practices and the handling, storage and shipping techniques improved commercial production. These investigations have resulted in the selection of several improved cultivars and in the development of shipping containers and conditions for overseas shipments.

The botanical family Solanaceae is among the more important groups of plants that provide a great number of useful fruits and products. Among the more prominent fruits are the tamarillo (Cyphomandra betacea), tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum) pepino (Solanum muricatum), naranjilla (Solanum quitoense), Cape Gooseberry (Physalis peruviana), tomatillo (Physalis philadelphica), eggplant Solanum melonga and chilli peppers (Capsicum spp.). Several important alkaloids and medicinals are derived from other members such as belladonna (Atropa belladonna) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum).

From Inca culture to commercial crop

The major development of tamarillo as a commercial crop has taken place in New Zealand where it has becoming a thriving industry. It was introduced into New Zealand in 1891, but it was not until World War II and the virtual isolation of the country in the mid-1940s, that the need for fresh fruits resulted in a wider local usage of the relatively unknown fruit. "Tamarillo" was adopted on January 31, 1963 by the growers of New Zealand as the official common trade name for Cyphomandra betacea. In many countries the common name is still some variant of the English term "Tree tomato". Slowly, however, the term "tamarillo" is being accepted in the trade to designate this attractive, though somewhat neglected member of the tomato family.

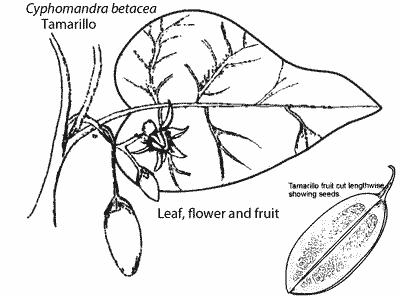

A few shipments to California indicated that the tamarillo is a rapidly growing evergreen subtropical fruit that can be injured by exposure to temperatures of about -20°C to -30°C. The shrubby tree can attain a height of 3 to 4 metres, but should be maintained as a smaller tree, as the rather soft-wooded stem tissue is especially susceptible to wind damage. Limb breakage is often a problem especially as the plant tends to bear heavy clusters of fruits at the tips of the long branches. The plant should be trained by pruning back long shoots and pinching shoot tips to induce a compact growth and the production of the fruit clusters near the centre of the tree. The plant is adaptable to a wide range of soil conditions, but thrives best in well-drained soils. The roots are shallow, hence the plant wilts easily under water stress and should be irrigated frequently. The large leaves - up to 30cm in length - are simple, entire and elongated heart-shaped, with a short petiole; the young leaves are covered with soft pubescence. The succulent new shoots and the leaves have a somewhat unpleasant odour when crushed. The flowers are borne in pendant racemes at the tips of the branches and are very fragrant and white or light blue to pinkish in colour. There is no apparent pollination problem as the plant is self-fertile. Pollen transfer is accomplished by bees or shaking of the branches by the wind.

The fruit is a berry of two cells with many seeds attached to the central placenta. It is an oval in form, somewhat pointed at both ends, and with a thin, smooth skin. The colour of the fruit ranges from a greenish or dark purple, to dark red, orange or yellow when ripe. The flesh is succulent, subacid in flavour and generally agreeable, somewhat like the ordinary tomato. There is a bitterness often associated with the skin and the tissue immediately under the skin. These tissues should be removed before cooking or when using the fruit fresh as in a salad. The rather hard rind withstands rough handling and prolongs the storability of the fruit.

Cultivars

Extensive investigations in New Zealand on all aspects of tamarillo culture and usage have resulted in the selection and development of several cultivars of superior qualities. Among these cultivars are New Black, a hybrid with a large fruit which was selected about 1927 by William Bridge. Ruby Red, has been the standard cultivar of the New Zealand industry for many years. Oratia Red is a large heartshaped fruit, deep red in colour and of sweet taste, selected by D.J. W. Endt in 1970. Inca Gold is an amber coloured, oval and slightly pointed fruit especially suitable for canning. Ecuadorian Orange is another selection with a fruit colour between yellow and red. Kaitaia Yellow was selected in 1979 for its good flavour, sweetness and suitability for processing. Goldmine is a cultivar under trial in New Zealand. Rothemer is a large 85-gramme fruit with a bright red skin and goldenyellow flesh, which was developed at San Rafael, California. Solid Gold is a sweet, orange fruit. Red Delight, Yellow and Oratia Round are also grown in New Zealand.

In general, yellow-fruited cultivars are considered sweeter and preferable for use as fresh fruit and in processing. Red types tend to be more acid; the pigment stains badly and causes corrosion when in contact with metal surfaces.

Seedlings as well as rooted cuttings tend to come into bearing early, within one and a half to two years under good cultural conditions. The tree will continue to bear good crops for 10 to 12 years. In poor soils or soils where nematode infestations or virus infections are possible prevalent, replanting with clean stock will be necessary and is recommended after a period of three or four years.

Cultural requirements

The tamarillo requires full sun and freedom from competition with roots or shade from other plants. It has a shallow root system, hence is easily uprooted in a strong wind. Fertile soil, good drainage, ample water and protection from winds are needed for good growth. Prune to reduce the tree height and shorten lateral branches again to reduce wind damage.

Propagation

Propagation is usually from seed, producing offspring with fruit reasonably similar to the parent fruit. Rooting of stem or root cuttings is frequently practised as this assures the retention of the cultivar's characters. Propagation by rooting of cuttings, however, does involve the risk of transmission of a virus disease which infects some plants and which should be avoided in the selection of parent material. For seed propagation, the pulp is fermented and the seed separated from the pulp with a sieve, washed and dried, soaked in a fungicide for a short time and planted about 5-6 mm deep. The seed bed should be maintained in a warm "dry-moist" condition.

Tamarillo can be grafted on several other closely-related rootstock species. In Java, Cyphomandra costaricensis is sometimes used as a rootstock to attain a longer-lived plant. It should be noted that many relatives of tamarillo in the family Solanaceae contain powerful and frequently undesirable alkaloids which can be transmitted to scions and into fruits grafted on such roots. Intergrafting of tamarillo on unknown or unevaluated rootstock is not recommended.

Pests and diseases

The tamarillo seems to be free of most common pests and diseases found in other cultivated plants. It is resistant to tobacco mosaic which affects many plants. However, cucumber mosaic, tamarillo mosaic and tomato aspermy virus have been found in tamarillo in New Zealand, possible spread by aphid or nematode vectors. Propagation by seed can avoid these viruses, but may result in unpredictable quality of fruit in some trees. Tamarillo is susceptible to the same soil-borne fungus, verticillium wilt, that affects tomatoes, eggplant and potatoes. A major pest on tamarillo is the tomato worm, the larva of the pyraustid moth Neoleucinodes elegantalis that also attacks the ordinary tomato and the pepino. Nematodes are a major problem in some areas. They affect the shallow root system and reduce the vigour and life of the plant. In soils heavily infested with nematodes it is frequently necessary to replant with new seedling material after two or three years. Aphids and white flies are sometimes a problem. In areas of high humidity, powdery mildew and anthracnose will sometimes attack the leaves or fruit to cause defoliation and loss of crop. [The RHS Dictionary of Gardening says it is particularly susceptible to the Red spider-mite. Ed.]

Using the fruit

The tamarillo fruit has been described as "brazenly beautiful" and the aroma "unusual and attractive". While the central soft, edible portion is sweet and has many uses as a fresh fruit, there is a thin tissue layer under the skin to which some palates are sensitive. The fresh fruit is best utilised by spooning out and eating the soft interior. For use in fresh fruit salads, the skin can simply be peeled off, or removed from the stem end after plunging the fruit in boiling water for a minute. Another way of removing the skin is to hold the fruit in a flame for about half a minute until the skin splits and bubbles.

The fruit can be used much as a regular tomato, but it has less moisture, so more water, stock or gravy is needed for most cooked dishes. The fruit is used as a garnish in salad, as slices in sandwiches, as a stewed fruit, a jam or chutney. It can be bottled or canned, but only the lighter-coloured fruits are suitable for canning as the dark-coloured fruits become unattractive in the processing. Custards, pie and cake fillings or syrupy compotes are other preparations made from the fruit. A pleasant wine can be produced from the tamarillo.

DATE: March 1997

* * * * * * * * * * * * *