POSTHARVEST HANDLING TECHNOLOGY FOR NEW TROPICAL AND SUBTROPICAL FRUIT CROPS

ABSTRACT

Many new tropical fruit crops, which include rambutan, carambola, sapodilla, durian and mangosteen, are now being grown in Queensland. Several of these crops are consumed in large quantities in south-east Asia, and because our production season is different from theirs, an export potential exists. There are also believed to be considerable market development opportunities within Australia for these fruits.

Limited information is available on the postharvest physiology and disease characteristics of these fruits. Following the successful development of postharvest technology for lychee, experimental study has been expanded to include these five fruits.

INTRODUCTION

The lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) was introduced into Queensland by the Chinese during the gold rush era of the late 1800s. During the 1970s, the industry started to expand with commercial plantings in coastal Queensland and northern New South Wales. After a 3-year co-operative study commencing in 1976, postharvest technology was developed for the long distance non-refrigerated transport and marketing of lychee fruit (1). The techniques were further tested experimentally in Australia (2) and in China (3,4).

Over the past nine years, some 285 different varieties of 36 species of new tropical fruit crops have been introduced into Queensland (5). This work has been led by Mr. B.J. Watson, Senior Horticulturist at Kamerunga Horticultural Research Station, Redlynch (6,7). Interest in the newly-emerging tropical fruit crops has been accelerated by active membership of organisations such as the Rare Fruit Council of Australia, The Sunshine Coast Subtropical Fruits Association at Nambour and the Exotic Fruit Growers Association at Lismore. Plantings of new tropical tree fruits have gained impetus. Some 4000 rambutan, 1200 carambola, 900 sapodilla, 800 durian and 3300 mangosteen have been planted in addition to the large expansions which have occurred in established crops such as mango, avocado and lychee.

Several of these new crops are consumed in large quantities in south-east Asia and because our production times are different from theirs, an export potential exists (8). Also, domestic market demand by both Asian and European groups in Australia continues to exceed supply.

Limited information is available on the postharvest pathology, physiology, handling and marketing of fruits such as rambutan (9,10), carambola (11,12,13,14) and sapodilla (15,16). Although further experimental study is necessary on packaging and cooling technology for lychee fruit, the technologies can be applied to selected new fruit crops with market potential.

This paper reports on current postharvest studies of rambutan, carambola, and sapodilla.

POSTHARVEST STORAGE OF RAMBUTAN (Nephelium lappaceum L.)

Materials and Methods

Two varieties of rambutan (R156, a yellow-skinned fruit) and (R3, a red-skinned fruit) were obtained from Kamerunga Horticultural Research Station. The fruit were airfreighted on the day of harvest to the laboratory at Hamilton in an unsealed polyethylene bag to prevent dehydration. Sound, fully-coloured fruit of each variety were treated with a fungicidal dip (0.5 g/l benomyl at 52°C for 2 min.) and air-dried at 20°C. Random samples of 5 fruit each were packed into clear plastic punnets and overwrapped with a PVC clingwrap plastic film (9μ thickness). The punnets were then stored at 25°C for 0, 5, 8 and 12 days, or at 5°C for 0, 7, 13, 18, 22 and 25 days. Unwrapped control fruit were also stored at each temperature.

Ratings were done by a five-member panel for general appearance (hedonic scale of 1 - dislike extremely to 9 - like extremely), skin/pulp colour (5 point scale of 0 - no discolouration to 4 - severe discolouration) and pulp flavour/texture - hedonic scale of 1 to 9.

Results

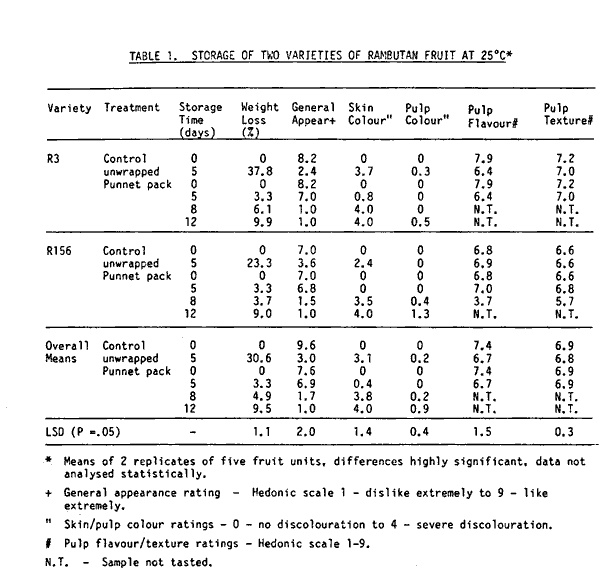

Storage at 25°C. Within 48 hours, spinterns of the unwrapped fruit had dehydrated and become brown and brittle. After 5 days at 25°C, these fruit had 25 percent weight loss and were uniformly brown and discoloured (Table 1). Fruit appearance was unattractive (general appearance ratings 2.4 R3, 3.6 R156) although the aril was still acceptable (flavour and texture ratings 6.0). Unwrapped fruit of variety R3 had significantly higher percent weight loss (37.8%) than variety R156 (23.3%). This difference was not evident in the punnet pack, in which the plastic film effectively controlled moisture loss. Fruit in the punnet pack was still in a fresh condition after 5 days at 25°C (general appearance ratings 7.0 R3, 6.6 R156). Weight loss was low (3.3%) and there was no skin discolouration or skin rots and the aril was acceptable (flavour and texture ratings 6.0). After 8 days at 25°C, punnet-packed fruit had deteriorated to an unacceptable quality with weight loss of approximately 6 percent.

The overall means indicated that there was a linear rate of weight loss during storage with rapid deterioration in general appearance and in eating quality of the fruit after 5 days. Dehydration (i.e. weight loss) was an important factor in skin browning but some other factor appeared to contribute to the more rapid quality deterioration after 5 days (i.e. at 3.5% weight loss).

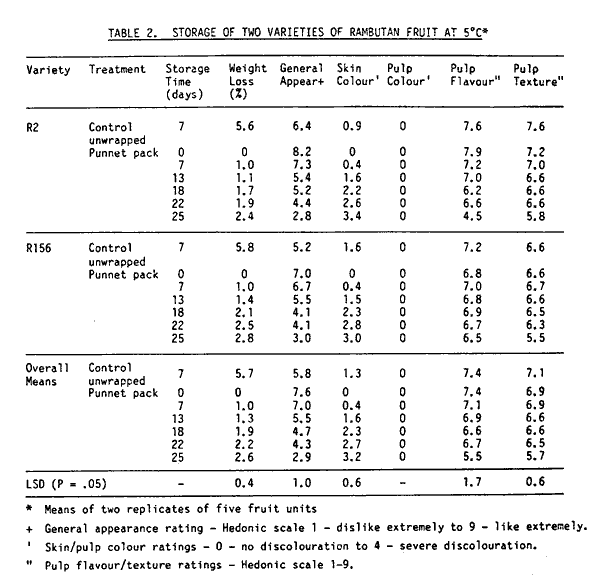

Storage at 5°C. After 7 days at 5°C, unwrapped fruit had 5-7% weight loss and general appearance was just acceptable (rating 5-8). However pulp eating-quality was still high, indicating that with control of skin discolouration, 5°C was a satisfactory cool storage temperature (Table 2).

Fruit in the punnet pack was still in a fresh condition after 7 days at 5°C (general appearance rating 7.0, weight loss 1.0%). However after 13 days of storage, fruit appearance was no longer acceptable (general appearance 5.5, skin discolouration 1.6) although the edible flesh had acceptable flavour and texture for up to 22 days of storage.

There was a significant difference in eating quality between the two cultivars. Although fresh fruit of R3 had better flavour than R156 and texture ratings of R3 during storage were higher than R156, R3 lost flavour at a significantly higher rate during storage than R156.

Discussion

The heated benomyl dip effectively controlled postharvest rotting, although during storage an apparent skin rot was observed as brown spots on the inner surface of the pericarp.

At 25°C, it was necessary to control weight loss to less than 5 percent for maximum retention of fresh quality. However, some postharvest factor other than moisture loss appeared to cause a significantly greater decline in fruit quality after about 5 days. During storage at 5°C, skin appearance declined linearly during the storage period even though weight loss was controlled, but acceptable fruit quality was maintained for 9 days.

Differences observed during storage of these two cultivars (weight loss at 25°C, flavour and texture changes at 5°C) indicated that there would be some variation in the storage behaviour and the optimal conditions of storage of the various cultivars of rambutan.

POSTHARVEST STORAGE OF CARAMBOLA (Averrhoa carambola L.) Materials and Methods

Cool Storage

Samples of 5 sound fruit were selected at a mature green-skinned stage from each of five varieties of carambola (Fwang Tung, Arkin, Leng Bak, B16 and B8). The fruit were stored for 1, 2 and 3 weeks at 5°C, 10°C, 15°C and 20°C. After storage, each fruit was weighed to determine percent weight loss and rated by a 5-member panel for skin colour (scale of 1 = mature green to 6 = fully yellow) skin rots and wing edge discolouration (0 = nil to 4 severe) and flavour, texture and general eating quality (hedonic scale of 1 = dislike extremely to 9 - like extremely).

A representative sample of juice was extracted and analysed for percent soluble solids (by refractometer) pH and titratable acidity (mls O.IN NaOH).

Storage in plastic film packages at 20°C

Five individual fruit of each of four varieties (Fwang Tung, B1, Leng Bak and Maha) were selected

at a mature green-skinned stage. Each fruit was then packaged in four different plastic films, viz:

Goodyear Vitafilm ® - PVC clingwrap film ( 9μ)

W.R. Grace D. film ® - cross-linked polyolefin film (19μ)

W.R. Grace PY 30 ® - "crispywrap" polypropylene film (15μ)

Polyethylene bags - 0.02 mm thickness.

(® registered trade name.)

The packaged fruit were stored at 20°C for 1 week then weighed to determine weight loss. Ratings and analyses were carried out on each fruit as in the cool storage experiment.

Results

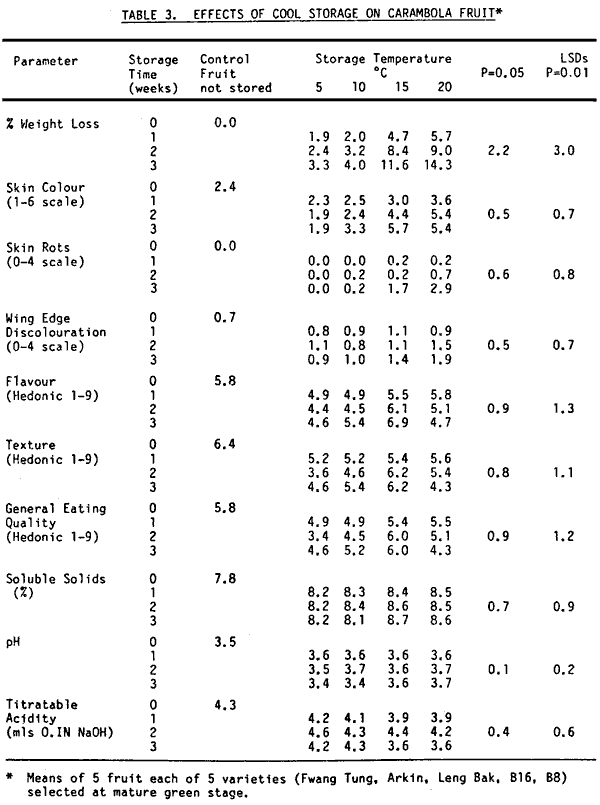

Cool Storage. At storage temperatures of 5°C and 10°C, percent weight loss of fruit reached 4% after 3 weeks of storage without increase in skin rots or wing edge discolouration (Table 3). At 15°C and 20°C, percent weight loss exceeded 10% after 3 weeks of storage and wing edge discolouration and fruit rots increased with storage. However, at 5°C and 10°C, there was a reduction in skin colour development, flavour and texture whereas at 15°C and 20°C, skin colour developed during storage and eating quality improved with a reduction in acidity of the fruit.

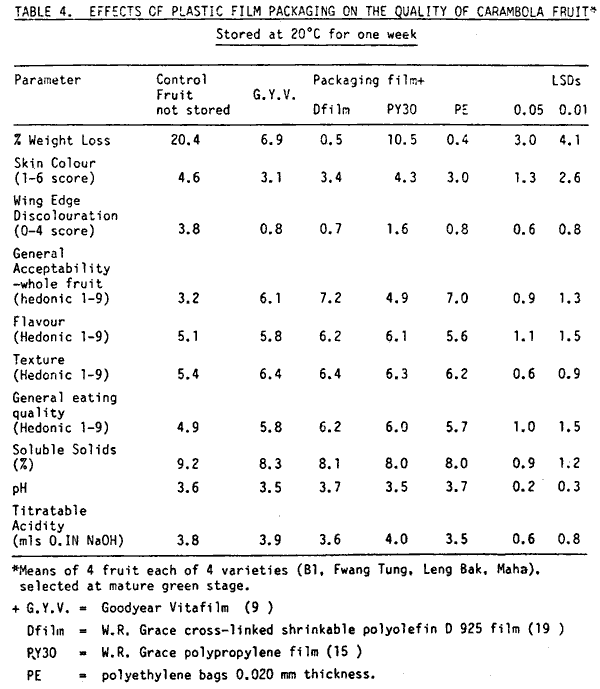

Plastic film packaging. Two of the plastic films (polyolefin film and polyethylene) retained fresh quality and controlled weight loss and wing edge discolouration of the fruit for 1 week, but skin colour did not develop (Table 4). PVC cling wrap film retained acceptable eating quality for 1 week without significant increase in wing edge discolouration, but weight loss was high (6.9%) and skin colour did not develop. Fruit in the polypropylene film developed yellow skin colour but had a high weight loss (10.5%) with an increased wing edge discolouration and loss of fresh quality.

Discussion

Because carambola is a non-climacteric fruit (12), eating quality does not improve after harvest, but rather it improves with ripeness level at harvest from mature green up to full colour. Therefore carambola fruit should be harvested as fully mature, ripening fruit (i.e. showing skin colour change up to full colour). Data in Tables 3 and 4 indicate that the fresh quality of fruit harvested at this stage could be maintained by suitable plastic film packaging for at least 1 week at 20°C, the most important factor being control of moisture (and weight) loss. Cool storage at 5° - 10°C would extend the post-harvest life of the fruit to at least 3 weeks.

POSTHARVEST STORAGE AND RIPENING OF SAPODILLA (Manilkara zapota L.)

Materials and Methods

Cool Storage

Forty-eight fruit were selected from each of two varieties of sapodilla (Krasuey, Kai Hahn).

Twenty-four fruit were placed in cool storage at 0°, 5°, 10° and 20°C for 1, 2 and 3 weeks. The other 24 fruit were ripened with ethylene gas (100 ppm) at 20°C until the fruit had reached first detectable softening (determined by manual finger pressure). These fruit were then also placed in cool storage.

After the storage period, each fruit was weighed to determine percent weight loss then assessed by a 5-member panel for flavour, texture and general eating quality (hedonic scale 1 to 9). A representative sample of pulp from each fruit was analysed for percent soluble solids, pH. percent titratable acidity and percent total solids.

Fruit maturity at harvest

Fruit of two varieties of sapodilla (Krasuey, Sawo Manila) were selected by visual appearance and divided into 3 maturity categories viz. M1 - light brown skin, tinge of green; M2 - light brown skin; and M3 - dark brown skin. Four fruit of each maturity category were analysed for percent soluble solids and percent total solids.

Results

Entomological identification. Sound unblemished fruit were selected from each consignment.

However after about 8-10 days of postharvest storage, individual fruits developed watery soft pulp associated with moist dark areas of skin. Inspection of affected fruit by officers of Entomology Branch showed that this disorder was caused by:

(i) fruit fly (Dacus sp.) - puncture wounds and larvae were found.

(ii)Drosophila sp. - a secondary infection developed.

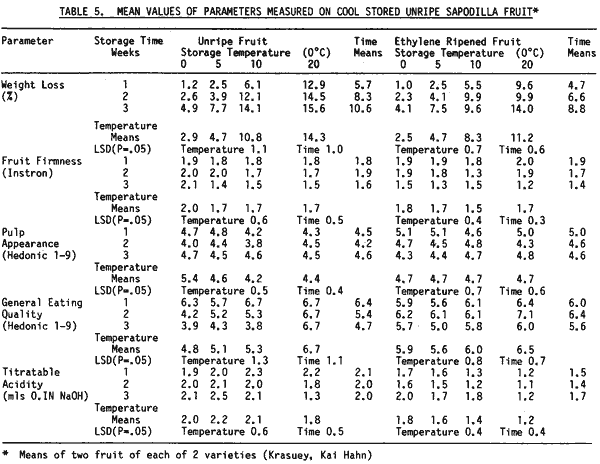

Cool Storage. Unripe fruit and fruit ripened to first detectable softening with ethylene gas, were cool stored. The most important change during storage was weight loss which increased with storage time and storage temperature (Table 5). Percent weight losses were greater in unripe fruit than in pre-ripened fruit. Fruit firmness did not change greatly during storage although pre-ripened fruit tended to soften with storage time. Ratings for pulp appearance were low for all fruit. Flavour, texture and general eating quality of unripe fruit stored at 0°, 5° and 10°C were unacceptable after 1 week's storage, whereas fruit stored at 20° had acceptable eating quality for 3 weeks. Fruit pre-ripened with ethylene gas retained acceptable eating quality at all storage temperatures for 3 weeks.

Chemical analyses of fruit pulp percent soluble solids, pH, percent titratable acidity and percent total solids did not show significant change with storage temperature or storage. Pre-ripened fruit had lower levels of acidity then unripe fruit.

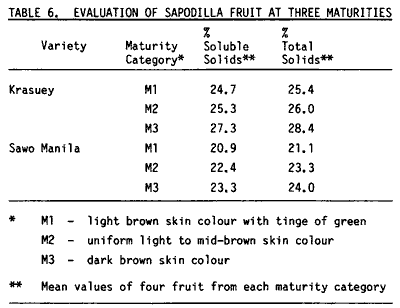

Fruit maturity at harvest.

Limited data in Table 6 showed an increase in percent soluble solids and percent total solids of pulp with increasing fruit maturity, as judged by external appearance.

Discussion

Cool storage data indicate that unripe sapodilla fruit ripened in storage at 20°C but that ripening was inhibited at temperatures below 10°C. The results suggest that unripe sapodilla fruit could be stored in a humidified atmosphere at 0°-10°C for up to 3 weeks, controlled ripened with ethylene gas then cool stored as ripened fruit for a further 3 weeks. Optimal conditions for cool storage have yet to be determined.

The limited data on fruit maturity (Table 6) and on ripe fruit quality indicate the possibility of developing a market standard based on soluble solids or total solids. This might also be correlated with exudation of latex, which was observed to be a problem not only with stage of fruit maturation but also during the initial stages of fruit softening during the ripening phase. Sensory ratings for ripe sapodilla indicated that market acceptance of this fruit, at least by European consumers, may be limited.

CONCLUSION

Available postharvest technology for packaging and cooling has been applied to three new fruits of different postharvest characteristics, selected from a large range of emerging tropical fruit crops. However, it may be necessary to select particular varieties to suit domestic and export markets and develop postharvest handling and marketing techniques for each crop. Also it appears likely that consumer education on handling, preparation and consumption of these new fruit crops will be necessary.

REFERENCES

1. Scott, K. J., Brown, B.I., Chaplin, G.R., Wilcox, M.E. and Bain, J.M. 1982. The control of rotting and browning of litchi fruit by hot benomyl and plastic film. Scientia Hort. 16: 253-262.

2. Tongdee, S.C., Scott, K.J., and McGlasson, W.B. 1982. Packaging and cool storage of litchi fruit. C.S.I.R.O. Fd. Res. Q. 42: 25-28.

3. Huang, P.Y. and Scott, K.J. 1984. Control of rotting and browning of litchi fruit after harvest at ambient temperatures in China. Trop. Agric. (Trinidad) 62: 2-4.

4. Brown, B.I. 1984. Report on consultancy on postharvest technology for lychee to the People's Republic of China Zhunghua County, Guangdong Province 11 Ju1y-1 August, 1984. Qld. D.P.I. Rept.

5. Page, P.E. (Compiler) 1984. Tropical Tree Fruits of Australia. Qld. D.P.I. Inf. Ser. Q183018.

6. Watson, B.J. 1978. An appreciation of five exotic tropical fruits and their potential in Queensland. Qld. D.P.I. Hort. Branch Thesis.

7. Watson, B.J., Lewis, W.J., Maggs, D.H. and Page, P.E. 1984. Austrofruit 1. Qld. D.P.I. QB 84005.

8. Pilavachi, T.G. (Mission Leader) 1984. Report of the Australia fresh tropical fruit and vegetable survey mission to South-East Asia. Comm. Aust. Dept. of Trade.

9. Lam, P.F. and Ng, K.H. 1982. Storage of waxed and unwaxed rambutan in perforated bags. Rept. No.251, Food Tech. Div. MARDI, Malaysia.

10. Lam, P.F. 1982. Low temperature storage of rambutan with and without skin. Rept. No. 244, Food Tech, Div. MARDI, Malaysia.

11. Oslund, C.R. and Davenport, T.L. 1983. Ethylene and carbon dioxide in ripening fruit of Averrhoa carambola. HortSci. 18: 229-230.

12. Lam, P.F. and Wan, C.K. 1983. Climacteric nature of the carambola (Averrhoa carambola L.) fruit Pertanika 6: 44-47.

13. Wilson III, C.W., Shaw, P.E. and Knight, Jr., R.J. 1982. Analysis of oxalic acid in carambola (Averrhoa carambola L. ) and spinach by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Agric. Food Chem. 30: 1106-1108.

14. Hall, N.T., Smoot, J.M., Knight Jr., R.J. and Nagy, S. 1980. Protein and amino acid compositions of ten tropical fruits by gas-liquid chromatography. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 28: 1217-1221.

15. Biale, J.B. and Barcus, D.E. 1970. Respiratory patterns in tropical fruits of the Amazon basin. Trop. Sci. XII: 93-104.

16. Broughton, W.J. and Wong, H.C. 1979. Storage conditions and ripening of chiku fruits (Achras sapota L.) Sci. Hort. 10: 377-385.

DATE: November 1985

* * * * * * * * * * * * *