THE CAROB

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Ceratonia siliqua

FAMILY: Fabaceae

SUMMARY

The Carob is an evergreen tree which produces a pod that has a great many economic uses. These uses range from so-called 'health foods' to industrial gums. Demand for Carob products is currently increasing.

The tree is traditionally grown in Mediterranean regions, however changes in agricultural production linked to population growth in these areas has reduced production of the Carob.

It seems, therefore, that Australia could become a Carob-producing country, as the general climate in many areas suits the growth of the Carob. At present, all of the Carob used here is imported.

In the future, hopefully, this situation will change from Australia being a net importer of Carob to being a net exporter of processed Carob products.

THE CAROB, AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE IN AUSTRALIA

As early as 1892 there was some interest in the Carob as an economic crop for the Colony of New South Wales. Turner, in the paper titled "The Cultivation and Uses of the Carob Bean", wrote highly of the tree and suggested the Carob as being a new commercial crop for New South Wales. (1)

A quote from Turner reveals this, "To encourage the cultivation of this valuable tree, the department last year distributed a quantity of seed, and some healthy young plants raised from this seed are now growing in several parts of New South Wales". (2)

Since 1892, little seems to have been done with the Carob in New South Wales or in any other state of Australia. It has been in the last decade or so that the Carob has been 're-discovered' in this country.

THE BOTANY OF THE CAROB

The Carob is an evergreen tree of the family Leguminosae (or Fabaceae), subfamily, Caesalpiniaceae.

The Carob tree under favourable conditions may reach heights of up to thirteen metres and can have a trunk girth of up to three and half metres.

The tree has pinnate leaves with usually four to five pairs of oval-shaped leaflets, these leaflets are a much darker green on the upper surface, as opposed to the under surface which may be light green to grey in colour.(3)

The leaves have a leathery texture which no doubt has a water-retention function.

The Carob tree develops quite a long tap root which penetrates deeply into the soil. It has been reported that roots had been traced down to twenty metres on some Carob trees in Algeria; the advantage of such roots is evidenced in arid areas with artesian water supplies where the tree can access these supplies to its advantage. (4)

The tree also develops extensive lateral root systems; this tends to occur more frequently in soils which are based on clay. (5)

Unfortunately, no report has ever been made of the Carob being involved in symbiotic nitrogen fixation although the Carob is a legume. (6)

The Carob is polygamous, the majority of trees are dioecious with a very small number of trees being monoecious. (7)

The flowers of the Carob are borne on lateral racemes, four to ten centimetres long, arising from the older branches of previous seasons. This leads to the formation of what are best described as warty structures.

The pods develop from the female flowers but only a small number of these flowers, usually two to five, actually produce pods. (9)

The pod may grow to a length of up to twenty-eight centimetres in some of the cultivated varieties of Carob.

A downfall of the Carob is that the tree will not usually bear pods until an age of between five and nine years, and even then there must be sufficient male and female trees.

CALENDAR OF GROWTH

Observations made over two years of mature Carob trees growing on the Liverpool Plains of New South Wales has yielded the following information. In summary, the trees flower in March and April with the pods developing through the Winter, Spring and Summer, when the pods are fully ripe in February.

CLIMATIC REQUIREMENTS

The ideal climate for the Carob is that of the Eastern Mediterranean. Minimum temperatures of minus six to seven degrees Celsius will cause a reduction in tree growth, temperatures of minus nine degrees Celsius and below will result in defoliation, and under prolonged periods at these low temperatures, the tree will die. (10)

The tree can grow at maximum temperatures in the order of fifty degrees Celsius with relative humidity of six percent. (11)

The optimum annual rainfall for the Carob tree is approximately six hundred millimetres. It is generally believed that poor pod crops would result under conditions of less than three hundred and twenty five millimetres per annum. (12)

Under extremeIy wet conditions which induce waterlogging, there is a likelihood of the tree being stunted or dying.

During the season when the pods reach maturity, there should be a minimum of rainfall. If there is rainfall, the ideal are falls of a short duration. Prolonged rainfall will result in fungal attack on the ripening pods, which then leads to the fermentation of sugars in the pod.

SOILS AND FERTILISER REQUIREMENTS

The Carob tree will grow in many different soil types, but the tree grows best in a deep, rather heavy loam, which has good sub-surface drainage. (13)

Soils which are calcareous in nature, those with a limestone base, are especially favoured by the tree, although a highly alkaline pH is not required for growth. (14)

A number of writers have reported that the Carob tree does not favour clay soils which have a very high clay content. (15)

Contrary to this, Carob trees on the Liverpool Plains District of New South Wales, yield quite well, although this area has soils which are based on expanding clay. Naturally if a clay problem did exist, an application of gypsum may reduce it.

Fertiliser requirements naturally vary depending upon local conditions, but in qeneral, a complete mineral fertiliser serves best. Under drip irrigation, a complete nutrient solution can be accurately supplied to each tree. Individual fertilizer treatments should be applied prior to flowering. Foliar analysis is recommended to ascertain those elements which are deficient, and those elements that may be at toxic levels.

The Carob is known to be slightly tolerant to saline conditions, but little in the way of research has been done on this specific issue.

PROPAGATION

The seed of Carob pods which have dried are extremely hard and dormant, no doubt a mechanism for survival in arid areas.

To accelerate the germination of seeds, it is best to soak the seed for one-quarter of an hour in water of a temperature of approximately eighty degrees Celsius and allow this to cool, leaving the seeds to soak for twenty-four hours or so until a number of the seeds have swollen in size. Initial germination is always low and it is advisable to soak four to five times the number of seeds required. Seeds may also be treated with sulphuric acid for one hour and then washed thoroughly and soaked in water for twenty-four hours.

The swollen seeds then are planted either in the field or into pots. The best method, if the situation allows, is direct sowing of the seed into the field; the reason being that the tree never has to be transplanted. During transplanting, Carob tree seedlings often suffer root damage, which limits later tree growth.

If pots need to be used, the general rule "the deeper the better" should be applied due to the long tap root that the tree has. From experience, pots made of black polythene can be used. When the tree is around eight centimetres high it can be planted out.

A hole is dug in the location of planting and soaked with water, the bottom of the pot is cut out using a pair of cutters and the pot is then placed in the hole, making sure that plenty of soil is around the pot. Eventually the rest of the pot can be cut away if it has not already rotted away. This technique works very well.

A number of European writers have stated that the Carob can be grown from cuttings, but from experience using striking powder and warm conditions, this proves to be difficult. When cuttings do strike, the resultant root systems are inferior to those formed by seedlings. (16)

Trees which are being planted for commercial purposes should be spaced at ten-metre intervals in a quincunx pattern, this allows each tree a space of one hundred square metres and permits plantings of one hundred trees per hectare.

GRAFTING

The aim of grafting is to obtain suitable varieties and to increase productivity per tree. The rootstock should ideally be a Carob that is suited to local conditions. To graft any particular variety, it is suggested that both male and female vegetative material is obtained and once obtained be grafted as soon as possible. Male and female material should be grafted onto each tree.

PRUNING

Pruning is required in the early stages of growth when the tree is sometimes known to send up suckers. Pruning may need to be carried out when branches overcrowd or are damaged.

IRRIGATION

Irrigation techniques for the Carob tree are in a practical sense of one type, drip irrigation. Variable flow drippers are ideal for the Carob - these drippers allow the grower to accurately control the flow rate per tree, resulting in a more efficient use of water. These trees can also be supplied with nutrient solutions and fungicides through the drippers as required. Once the trees become established, the drippers can be removed or retained depending on the situation.

STAKING

The practice in countries such as Cyprus, is to stake the tree when it is around ninety to one hundred centimetres in height. (18)

The staked plants stand the negative affects of strong winds and tend to grow in a more vigorous fashion. (19)

GROWTH PROMOTION

One very evident problem of the Carob tree is the slow rate of growth the species has. A saying from Cyprus puts this aptly, "plant an olive tree for your children and a carob tree for your grandchildren". (20)

Two practices which can accelerate the growth of the Carob tree are the use of gibberelic acid, a plant hormone which promotes stem elongation, and the use of 'growtube', a polythene sock which is placed around the tree seedling in a similar fashion to a tree guard.

HARVESTING AND YIELDS

When the Carob pod reaches maturity, traditionally the pods are lightly beaten or tapped with a pole and fall to the ground. The pods are not damaged by falling to the ground. The pods are then raked or collected up by hand and bagged or placed in suitable containers. It may be the case that the pods may need to be dried to prevent the development of bacterial or fungal pathogens if the moisture content is high. Drying can be carried out using aeration tables made from fine netting and poles.

As yet, no mechanical harvesting methods for the Carob have been fully developed. There has been mention by some agriculturalists in this country of using Almond harvesters. This area of Carob culture needs to be more fully explored as hand methods would make the Carob costly to harvest given the high cost of labour in Australia.

There is great variation in yields of Carob pods due to factors such as variety, rainfall, and soil. Some reported yields per tree have been as high as six thousand kilograms, but it is sheer folly to expect all trees to reach this rare and isolated yield. (21)

Some data has suggested that a twelve-year-old tree can produce two hundred kilograms of pods and a twenty five-year-old tree can produce five hundred kilograms of pods per year. (22)

Given these yields, it would be reasonable to expect in good seasons, yields in the order of twenty tonnes per hectare, where there are one hundred trees per hectare.

It has to be realised that the Carob tree will bear heavy crops in alternate years and that yields will be variable from season to season.

CAROB VARIETIES

One of the most important Carob varieties is Tylliria from Cyprus. Ticho stated that Cyprus achieved world fame as a Carob producer because of this variety. (23)

The South Australian Department of Agriculture has the following varieties of Carob: Sfax, Clifford, Amele, Santa Fe, Cypriot, Tylliria, Lagona, Tantillo, and Baden. (24)

These varieties were imported some two or three years ago and are held at the Loxton Research Centre at Loxton in South Australia. In 1986 departmental research officers stated that budwood would be available in the future. (25)

However some personal communication with Mr. P.H. Thomson of California has revealed that existing Carob varieties in Australia are already of a high quality (26). Thomson reasoned that seed production from the Carob is far more important than the production of pod flesh and that varieties existing in Australia were very high quality seed producers. (27)

PESTS AND DISEASES

In Australia the major insect pest of the Carob is the Carob moth (Ectomyelois ceratoniae); this moth and its larvae can cause great damage to the pod, often resulting in secondary infection by fungal and bacterial pathogens. (28)

Management practices which reduce old crop residues and keep storage areas clean will limit the attack by insect pests.

Seedling diseases are common in the Carob when unsterilised potting mixes are used. The fungal pathogens Rhizopus and Mucor are often the cause of seed rots. Two other fungal pathogens, Fusarium and Rhizoctonia solani kill recently germinated seeds at emergence. (29)

Control is simple, in that seeds can be treated with a registered fungicide and sterilised potting mixes should be used.

Diseases which cause economic damage to adult trees have not been noted in Australia.

Vertebrate pests such as the rat (Rattus rattus var. frugivorus) in Cyprus and the Pocket Gopher (Geomys bursarius) in California are major pests of the Carob, however pests of this nature are generally lacking in Australia. (30)

Although mice and rat plagues may have an effect at infrequent times, vertebrate pests and livestock can cause extreme damage to young trees, but generally the use of suitable tree guards will prevent damage.

Avian pests have not been noted as pests of the Carob, however under commercial conditions it would be likely that avian pests of grain crops could attack the Carob. Under such conditions, control using nets may be required.

For commercial production of the Carob in Australia, it is imperative that an integrated pest management strategy be developed for this tree crop.

MARKETS AND USES FOR THE CAROB

Carob production is in decline in many of the traditional growing nations such as Cyprus. (31)

In Cyprus there has been a trend for farmers to pull out Carob trees and to grow crops such as potatoes, cereals, and citrus which have greater economic returns. Only the most marginal lands have been left to the Carob. (32)

With this decline, Australia could take advantage, as much of the climate here is suitable for the growth of the Carob as evidenced by the number of trees presently growing here.

Demand for Carob products has been increasing, the Carob having an advantage in that it does not contain caffeine. The development of healthier lifestyles in the Western World can only assure a further growth in demand.

The Carob has a multitude of uses some of which are: inks, pharmaceuticals, paints, stock feeds, drilling muds, ceramics, dog foods, sweets, paper, desserts, pastes, and cosmetics.

Australia would do best to concentrate on the export of processed Carob products, rather than exporting unprocessed pods or seeds. A reliance on the export of unprocessed primary products has been the cause in part for some of Australia's economic ills.

CONCLUSION

It would seem therefore that the Carob will be a new farm enterprise in Australia. Recently in Western Australia it was reported that some ten thousand Carob trees had been planted, thus indicating the interest in the tree.

On-farm kibbling plants could be constructed to process the pods, modified mix-alls might be able to be used for this by farmers.

Carob co-operatives would be formed by farmers, such as the Co-operative Carob Marketing Federation located in Limassol, Cyprus. (33)

The Carob is an adjunct to existing farm enterprises. The use of this tree will provide a stability to the land, reducing erosion, providing aesthetic value to the land and lifting farm productivity.

REFERENCES

(1) Turner, F. 1892. "The Cultivation and Uses of the Carob Bean". In Agricultural Gazette of New South Wales (3): 234-240.

(2) ibid.

(3) Coit, J. E. 1951. "Carob or St. John's Bread". In Economic Botany (5): 82-96.

(4) ibid.

(5) ibid.

(6) ibid.

(7). Esbenshade, H.W. and Wilson, G. 1986. Growing Carobs In Australia. Goddard and Dobson, Box Hill, Victoria.

(8) Coit, op.cit.

(9) ibid.

(10) Ticho, R. J. 1958. Report to the Government of Cyprus on Carob Production. F.A.O. Report No.974, Rome.

(11) Coit, op.cit.

(12) ibid.

(13) Ticho, op.cit.

(14) Coit, op.cit.

(15) ibid.

(16) ibid.

(17) ibid.

(18) Nouri, Q. 1937. Cyprus Agricultural Journal (2): 109-16.

(19) ibid.

(20) Orphanos, P. I. 1980 "Practical Aspects of Carob Cultivation in Cyprus" In Separata De Portugalica Acta Biologica.(16): 221-228.

(21) Coit, op.cit.

(22) ibid.

(23) Ticho, op.cit.

(24) Personal Communication - South Australian Department of Agriculture.

(25) ibid.

(26) Personal Communication - P.H. Thomson.

(27) ibid.

(28) Esbenshade, op.cit.

(29) ibid.

(30) Coit, op.cit.

(31) Personal Communication - P.I. Orphanos.

(32) ibid.

(33) Personal Communication - A Kestas.

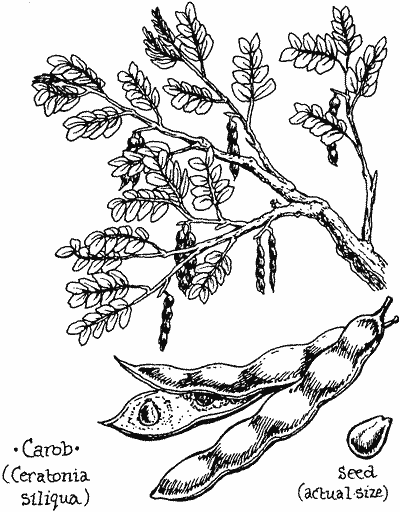

Drawing from Earth Garden No. 59 Feb/Mar 1988.

DATE: March 1988

* * * * * * * * * * * * *