CASSAVA CROPS UP AGAIN

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Manihot esculenta

FAMILY: Euphorbiaceae

First printed in New Scientist 17th June 1989, this excellent article by Rodney Cooke and James Cock answers all those questions about cassava you were too afraid to ask.

Cassava is a buttress against starvation in many countries - its starchy roots thrive in poor soils with little rainfall. But harvested cassava rots quickly and can poison people.

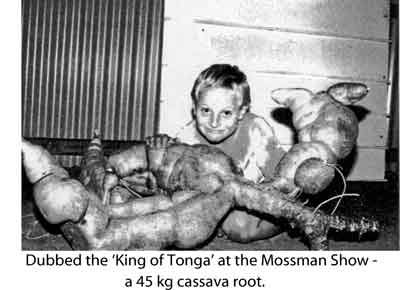

IT WOULD BE difficult to design a more appropriate food crop for the tropics than the cassava root. Cassava survives and produces a reasonable harvest even in the poor soils that characterize large parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America. It tolerates drought and acid soils. The cassava plant resists damage by pests and diseases and is one of the most efficient converters of solar energy to carbohydrate. Small farmers in tropical countries like the crop because they can propagate from stem cuttings and because they can intercrop it with other staples, such as maize.

People eat more than 60 per cent of all cassava produced. About a third of the harvest feeds animals and the rest is transformed into secondary products, such as starch. People eat the cassava root in virtually all tropical countries. The boiled leaves, which are an excellent source of protein, are eaten in many parts of West and Central Africa and in the Amazonian Basin. The Portuguese introduced cassava to the African continent from its home in Latin America.

Yet despite its many advantages and the fact that world production of cassava increased by 24 per cent between 1971 and 1981, the importance of cassava, relative to cereals, has decreased. Aid from the rich countries of the north has helped to promote the view that cassava is poor folks' food. Aid to developing countries often takes the form of subsidies for food that is not grown locally. For example, aid agencies and government typically supply cereals grown in the Northern hemisphere to countries where the staples are root crops, such as cassava or yams. City-dwellers may receive a further subsidy as governments keep the price of bread artificially low; they benefit directly at the expense of small local farmers whose crops cannot compete. In Brazil, subsidies make bread cheaper than cassava. Without a market for their crops, farmers leave the land for the city. In Latin America, the production of cassava fell by 12 per cent between 1971 and 1981, largely because of the availability of highly subsidized cheap wheat.

This move towards cereals in tropical countries destabilizes local agriculture and increases dependency on aid. The agricultural pricing policies of importing countries and the subsidies of exporting countries have further favoured cereals. Consequently the consumption of cereals in tropical countries has increased while the consumption of cassava and other tropical root crops has declined. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, cereal imports amounted to US $2 billion a year in the early 1980s. This dependency on imported food, and the consequent neglect of traditional local crops that can give excellent yields in tropical climates, is a disturbing trend. The picture is changing, however, because of the uncertainties associated with long-term food aid, and the trend towards agro-industrial development in tropical countries.

Many development projects that attempt to replace direct subsidies by improving agricultural methods have compounded the problem because they have not built on local traditions: inappropriate crops or damaging technologies are introduced. For example, tractors at first improved the yields of crops in tropical Africa, but after a few years they destroyed the fragile structure of the topsoil, causing massive erosion. Other development projects have ignored staples such as the roots and tubers that, in tropical countries, people grow mainly for their own consumption. Women are often responsible for the cultivation, harvesting, processing and marketing of these staples. Consequently, traditional crops such as cassava have a low social status and, in the past, have attracted little research.

There are other reasons for the neglect of cassava, however. One disadvantage of cassava is that it is difficult to hold stocks for even a few days because the roots deteriorate quickly after harvest. Research aimed at increasing the productivity of cassava and finding ways to store it could support local agriculture, and benefit people for more than just a few years.

During the past 10 years, researchers from Britain's Overseas Development Natural Resources Institute have addressed these problems. The ODNRI is one of the scientific arms of Britain's Overseas Development Administration. Work on cassava began by examining the biochemical, physiological and pathological characteristics of the deterioration of the root. The institute has now developed into research on cheap ways to store roots, and to improve the quality of fresh and processed cassava and its nutritional value. It hopes to increase the popularity of cassava, and so ensure the future of small farmers, by distributing the root to novel markets and finding new uses for cassava.

Cassava is grown principally by small farmers for their own consumption and for sale to local markets or processing plants. They avoid the problem of rapid deterioration by harvesting a few roots at a time. Women also process cassava soon after gathering it so that it can be stored for longer than a few days. In West Africa, women peel, wash and grate cassava tubers to prepare gari. They ferment the grated pulp in sacks under weights for a few days. Heating the fermented cassava drives off water and cyanide. The roots contain enzymes that convert certain glucosides into hydrogen cyanide, which can poison or kill people who eat it.

In tropical Brazil, women peel the tuberous roots, then pack the cassava into a stretchy basketwork tube, the tipiti, to extract the juice which contains most of the cyanogenic glucoside. They roast the damp meal over a fire, then use it for bread or dumplings. These elaborate ways of preparing cassava prolong its life considerably. Chips of dried cassava or dried and milled cassava can last even longer. Knowing how cassava deteriorates after harvest might suggest easier methods of preparation and more efficient ways of storage.

A collaborative project between the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in Colombia and the ODNRI has begun to unravel the two processes by which cassava roots perish. Cassava begins to rot within three days, often after 24 hours of harvesting depending on the damage a root has suffered. Microorganisms begin to promote the deterioration of the roots usually only after the cells of the root have been damaged. June Rickard, of the ODNRI, and Chris Wheatley, working first for Wye College, University of London (funded by the Overseas Development Administration), and later at the CIAT, showed that the root begins to deteriorate as the activity of oxidising enzymes in its cells increases. The enzymes generate phenols, such as catechins and leucoanthocyanidins, that later polymerise to form tannins. The first sign of damage shows up within 24 hours of harvesting as bright blue fluorescence under ultraviolet light, as the phenolic coumarin and scopoletin accumulate. Tannins then colour the white root tissue blue or brown, a condition known as vascular streaking. Damaged cassava cooks poorly and often tastes unpleasant; tannins may also bind to proteins in the gut, preventing their absorption. Storing the roots at low temperatures, keeping them in a humid atmosphere and excluding oxygen slow the deterioration.

Cassava can, however, cure itself: high temperatures and humidity promote the healing of wounds in the roots naturally. In these conditions, fatty substances move into the walls of the cells known as the parenchyma, forming a cork layer that resists decay and is waterproof. A layer of rapidly growing cells (similar to those in a root tip) forms beneath the wound, and minimizes the loss of water that leads to vascular streaking.

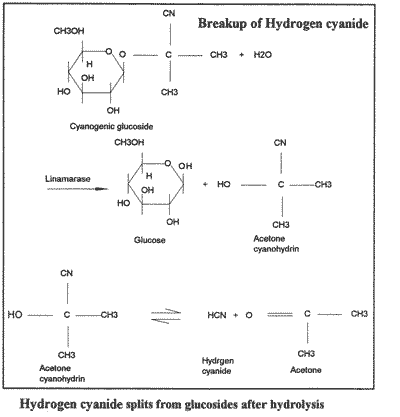

THE SOURCE of cyanide (-CN) in cassava are compounds called cyanogenic glucosides, such as linamarin and lotaus tralin. These consist of a glucose ring combined with a cyanohydrin, which has a cyanide group and hydroxyl group attached to the same carbon atom. When the cassava tissue gets damaged by, for example, grating it to a pulp, it liberates an enzyme called linamarase. This catalyses the reaction of a cyanoglucoside with water to release the glucose and the cyanohydrin, which can then decompose reversibly into a ketone, such as acetone (CH3COCH3) and free hydrogen' cyanide (HCN), depending on the conditions. An enzyme called hydroxynitrile lyase can catalyse this reaction.

Once the hydrogen cyanide is freed, it is easy to remove by heating (drying and roasting the cassava) because it is a gas. The cyanoglucosides and cyanohydrin are more difficult to get rid of, although cyanohydrin decomposes quite quickly at a neutral pH. Under acidic conditions, however, this reaction slows down dramatically.

Studies at the Overseas Development of Natural Resources Institute, Kent, show that the key factor determining how much cyanide is left in cassava foods depends on its preparation. In products based on whole roots or pieces of cassava, the rate at which the cyanogenic glucosides break up controls the amount of cyanide present. When the cassava is milled or pounded to a pulp, the conversion of cyanohydrins to hydrogen cyanide may become the limiting factor.

Homogenised cassava in water rapidly becomes acidic because the bacteria associated with fermentation produce lactic acid. The acidic conditions then slow down reaction b and stabilise the amount of cyanide present.

Studies at the CIAT showed that the rate of decay can vary depending on the variety of cassava and the environment in which it is growing. Plants whose roots are slow to rot contain less starch than those that decay rapidly, but they are not as valuable as a crop. So breeding for resistance to physiological deterioration will probably prevent an increase in the amount of starch in cassava. Instead, researchers need to look for ways to preserve the crop after harvesting.

Pruning the plant two or three weeks before harvesting causes the root to shrivel a little, but makes it keep better. Unfortunately, cassava treated in this way does not taste as good as that from unpruned plants; it takes longer to cook and has a different texture. Yet it might be a useful approach for animal feed.

Whatever treatment is used to preserve the root, about five days after harvest damage by microorganisms begins. Most of the early work to isolate the agents of decay in cassava concentrated on the later stages of this process. Bob Booth and Robert Noon, researchers from the ODNRI working at the CIAT, identified various species of moulds and bacteria, but consistently failed to isolate any specific microorganism from the advancing margin of rot in the cassava root. A variety of parasitic microorganisms (saprophytes) hasten secondary decay.

The ODNRI-CIAT project also investigated other ways to store cassava. Subsistence farmers commonly leave cassava in the ground until it is needed. However, this leaves the land underused, while the cassava often become tougher and less marketable. The risk of crop loss from pests and diseases increases. The success of other storage methods in pits, field clamps or in boxes with moist sawdust depended on achieving the curing conditions that slow down decay. First, researchers picked the best roots to store because digging up cassava sometimes damages a root so badly that curing is ineffective. Bob Booth, for the ODNRI and the CIAT (now with the United Nation's Food and Agricultural Organisation as coordinator of its programme to prevent food losses), reported that he had stored cassava for several weeks in field clamps, similar to those used for storing potatoes. Clamps are difficult to manage especially where seasonal variations in climates cause the requirements for ventilation and drainage to alter after the clamp has been sealed. Nor do cassava farmers and traders in Latin America need clamps if they sell only small amounts of cassava quickly. Storage in boxes proved too expensive for small farmers unless the cassava is to be exported, in which case farmers get a price high enough to make the boxes affordable.

Another way to keep cassava fresh is to pack it in plastic bags. A group at the CIAT led by James Cock, including Rupert Best, Carlos Lozano and Chris Wheatley, found that the high humidity and temperature within the polyethylene bag promotes root curing. Roots can also be treated with a fungicide, thiabendazole, to inhibit secondary damage by microorganisms. Thiabendazole is an approved fungicide for use in food products: residue levels in cassava are less than 1 part per million. (Permitted levels in potato are up to 5 parts per million.) This is an economic and safe use of an agrochemical. The procedure is simple, requires little capital or labour so farmers readily accept it. Treated cassava stores well for two to three weeks. Preliminary studies suggest that increasing sugar content in roots determines this limit. Field tests with Colombian farmers show that roots should be treated and packed within a few hours of harvest and that damage to roots should be minimised.

Future projects involving the CIAT and the ODNRI will concentrate on adapting the storage treatment to the requirements of different cassava-producing regions in Latin America. It solves some of the problems of getting cassava to city markets in good condition. In Colombia, economists estimate that the benefit to the urban population would be more than US$20 million a year because cassava stored in polythene bags and treated with fungicide is cheaper because of reduced losses and of better quality, This technique is also being used commercially in Paraguay, Ecuador and Panama.

There remains, however, the problem of toxicity. Cassava roots are starchy, and so a good source of carbohydrate, but they contain little protein. In times of famine, cassava is often the only food available. If roots are damaged or prepared carelessly, they will have a high content of hydrogen cyanide. Cassava foods may also contain residual cyanide that can cause nutritional problems. Some lines of cassava contain less cyanogenic glucoside than others, but researchers have failed to locate a cassava strain that is free of cyanide. The quantity of cyanide in commercially grown cassava is rarely sufficient to cause acute poisoning, but there are fears over the long-term effects of eating even minute portions of cyanogenic glucoside. Researchers first had to determine how much of this people were exposed to. The methods were tedious, irreproducible and inaccurate. Rod Cooke, of the ODNRI, developed an enzymic assay for the cyanide in cassava that obviates many of these problems. This has been used in field trials run by the CIAT, the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture in Nigeria, the Food Technology Research Centre (CITA) in Costa Rica and the National Institute of Technology and Standards (INTN), Paraguay. Other centres in Africa, India and the Far East have also adopted it.

Using this assay, a picture emerges of how effective traditional methods of removing cyanogenic glucoside are. In some cases the breakdown of the glucoside is the slowest step, in others the hydrolysis of the nonvolatile cyanohydrin to volatile hydrogen cyanide is the limiting step in the removal of cyanide.

An extended study in Zaire by A. M. Ermans and colleagues from the Hopitale St Pierre, Brussels, pointed to a link between eating cassava and the development of goitre and related neurological syndromes where dietary iodine is in short supply. Goitre was most common in areas where people ate large amounts of cassava. The human metabolic route for cyanide detoxification increases the requirement for amino acids containing sulphur (methionine). Furthermore, one of the products of detoxification, thiocyanate, inhibits the absorption of iodine. People who have sufficient iodine in their diet did not show signs of goitre.

Other factors also complicate the picture we have of cassava. For example, dried and processed cassava contain tannins. Tannins in other foods, such as sorghum, make it harder to digest proteins and to absorb iron and methionine.

So people eating large amounts of cassava may fail to absorb exactly the amino acids they need to protect themselves against its toxic effects. June Rickard and Nigel Poulter at the ODNRI, working with researchers led by John Blanshard from the University of Nottingham, hope to find out whether tannins in cassava products have similar effects.

Hans Rosling of the International Child Health Unit, Uppsala, Sweden and his colleagues in Mozambique are investigating the association between eating inadequately processed cassava at times of famine and a failure of the nervous system that controls muscles, spastic paraparesis (which is known throughout Central Africa as konzo). There appears to be a link if diets contain high levels of cyanide from eating poorly prepared cassava and are low in protein. During recent years, this disease has crippled several thousand women and children in Zaire, Mozambique and Tanzania when food is short in areas where cassava grows. Rosling points out that the toxic effects of cassava are slight compared with the other public health problems in tropical countries, and to cassava's importance as a staple food. In most cases where people have been poisoned, the only alternative for the families concerned was starvation.

The amount of cyanide left in cassava varies with the method of preparation. Introducing new varieties without regard for local ways of growing and processing roots and the local diet may cause problems. Good varieties of cassava can sell themselves, however. In Nigeria, researchers tested improved varieties of cassava by growing them in the poorest soil, without protection from pesticides. Local farmers quickly adopted the best cultivars and sold cuttings to neighbours as soon as their own fields had been planted.

Little research has been done, however, on why people prefer different varieties of cassava. So the IITA and the CIAT with the Rockefeller Foundation began a study of how cassava was grown and used in sub-Saharan Africa. The ODNRI helped to design surveys of how cassava is processed and sold. The CIAT and ODNRI are also investigating why some lines of cassava have higher yields yet to do not appeal to consumers, and how factors such as cooking time, taste and starch content depend on the age at which a plant is harvested, its environment while it grows and how the root is processed.

Alan Reilly, Andrew Westby and David Twiddy, microbiologists from the ODNRI, are examining the role of microorganisms in the detoxification of cassava when making gari and fufu, traditional African foods. Gari is a fermented granular cassava product, which is partly gelatinised, and is prepared in most of West Africa. Fufu is a creamy-white fermented paste eaten in Nigeria and Zaire. The microbiologists showed that two stages of processing eliminate most of the cyanide: grating raw roots and roasting the final product. The lactic acid bacteria, which predominate during fermentation, develop the flavour and extend the food's shelf-life but play little part in the breakdown of the cyanogenic glucosides.

The future for cassava may, however, lie with its secondary products: cassava chips make a nutritious animal feed; ground cassava can partially substitute for wheat in bread; and cassava can be fermented to make alcohol and single-cell protein. During the past 20 years, for example, Thailand has built up its exports of sun-dried cassava to 7 million tonnes a year. Shipped as compressed pellets, mainly to EEC countries, it is added to compound animal feeds. Many Latin American countries are producing cassava chips for their animal feed industries. In Ecuador, finely milled dried cassava acts as a nutritious additive that also helps to stick shrimp food together.

Starch and starch derivatives, such as dextrins, glucose and high-fructose syrup are the main products of the cassava agro-industry. Cottage industry production of starch dominates South America, Asia and Africa but larger scale operations in Thailand, Brazil, the Philippines and Indonesia produce 8 per cent of the world's starch. Starch is probably the most familiar cassava product outside the tropics: as tapIoca, rice-sized beads of cassava starch, it has probably been on most schoolchildren's plates.

Rodney Cooke is former head of the food plant department of the Overseas Development of Natural Resources Institute (ODNRI), and has recently become a deputy director.

James Cock leads the cassava programme at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture, Cali, Colombia. This article represents the personal views of the authors.

DATE: March 2002

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *