RESPIRATION, ETHYLENE PRODUCTION AND CHANGES IN THE INTERNAL ATMOSPHERE OF DURIAN

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Durio zibethinus

FAMILY: Bombacaceae

INTRODUCTION

The Durian is an important commercial fruit crop in several Southeast Asian countries including Thailand. It is one of the best known and most controversial of all tropical fruits (1). Vivid and delightful descriptions on the rich aroma by durian enthusiasts and its opponents add to its mystery to the western world. The large fruit vary from spherical to oval. The hard woody skin is covered with strong sharp prickles. The characteristic aroma develops rapidly as the fruit ripens. The ripe fruit could be torn from the basal end along a natural abscission layer on the skin into five locules of unequal size to reveal the white to creamy or yellow edible aril. Each segment of custard-like aril enclose up to 3 light-reddish-brown seeds. The fruit is best eaten raw. Export from Thailand is mainly in the form of fresh durian. Their pulp can also be stored by freezing. It is in this form that small quantities of durian are also exported.

Physiological investigations on fresh durian are limited. The fruit is classified as climacteric. Mathur and Srivasta (4) reported that durian can be stored for several weeks at 4 to 5°C at 85 to 90% relative humidity. The nature of the volatile constituents were reported by several workers (2,3). The few studies are of limited value in the explanation of fruit ripening processes. The rapidity the fruit ripens after harvest and the short period when the fruit is of best eating quality, made knowledge of the ripening processes essential. This present investigation examines the respiratory trend of the harvested durian of three major cultivars grown in Thailand, the relationship between ethylene production and the onset of the climacteric, and the level of internal CO2 and ethylene in the ripening fruit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Durians cv. Chanee, Kan Yao, and Mon Tong were obtained between mid- to late May 1986 from trees grown in a commercial orchard in Rayong Province, Thailand. Fruit were harvested at about 85% maturity. The judgement of maturity stage, a life-long art, was assisted by an experienced grower based on a combination of several criteria. These fruit were expected to ripen on day 5 to 6. Fruit weight varied from 2.1 to 2.9, 3.0 to 3.1 and 2.8 to 3.2 kg each for 'Chanee', 'Kan Yao', and 'Mon Tong' respectively. Fruit were transported and received in the Postharvest Technology Laboratory on the afternoon of the day of harvest. Fruit were kept in a room maintained at 22°C. All treatments were applied to the fruit on the next day.

Measurement of respiration and ethylene production: Individual fruit were placed in an 18-1PVC container ventilated with a continuous flow of humidified ehthylene-free air at 40 l/hr.

A 1-ml gas sample was taken from the outflow of each container with a hypodermic syringe for the determination of CO2 evolution and ethylene production. Measurement of CO2 was made with a Shimudzu 9-A thermal conductivity gas chromatograph with a Porapack R Column. For the determination of ethylene, a Shimadzu 9-A flame ionization gas chromatograph with an activated alumina column was used. Results were obtained from 3 replicate fruit.

Sampling methods for internal gases: 'Chanee', 'Kan Yao' and 'Mon Tong' durians were used. Daily monitoring of internal gases was made on the same fruit. Gas sample was taken using a method modified from the procedure used by Sattveit (5). A piece of rind 1.5 to 2.0 cm thick was removed with a sterile, 0.6mm-diameter cork borer. Care was taken not to injure the aril. The hole was then plugged with a short plastic tube of the same diameter sealed to the rind with synthetic rubber-cement. The outside end of the plastic tube was tightly plugged with a septum. The rind mainly consists of wood-like materials, thus injury to the rind was not expected to cause an increase in the internal CO2 or ethylene concentration. In case the aril was accidentally injured, stress would have stabilized by day 2 when gas samples were taken. Three such sampling ports were made on the equatorial region of each fruit. Fruit were placed uncovered in the laboratory at 22°C. Gas sample was withdrawn through the septum by a 1-ml hypodermic syringe. CO2 and ethylene was determined by gas chromatography as mentioned previously. Results reported were the average from three sample ports of a representative fruit of each cultivar.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

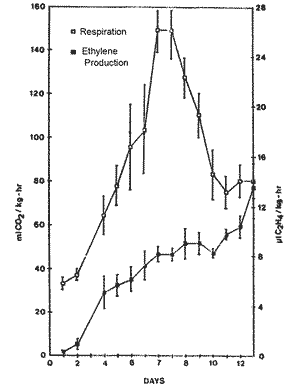

'Chanee' durian exhibited a climacteric respiratory pattern (Fig.1.) Rate of respiration, about 30 ml CO2/kg/hr steadily increased after harvest. Peak respiration rates, ranged 149 to 165 ml/kg/hr, occurred after 7 days and then declined. Pre-climacteric ethylene production was less than 0.02 μl/kg/hr. Ethylene production increased steadily from day 2 onward with peak ethylene production, 8.5 to 10.4 μl/kg/hr, occurred at day 8 and remained relatively high post-climacteric. Peak ethylene production was associated with senescencing tissue. Distinct aroma, an indication of the fruit becoming eating-ripe, was detected on all fruit at day 6, prior to the respiratory peak. There was no drastic change in skin colour when the fruit became eating-ripe. All fruit were over-ripe at the end of the experiment. A few fruit had turned yellow to yellowish-brown.

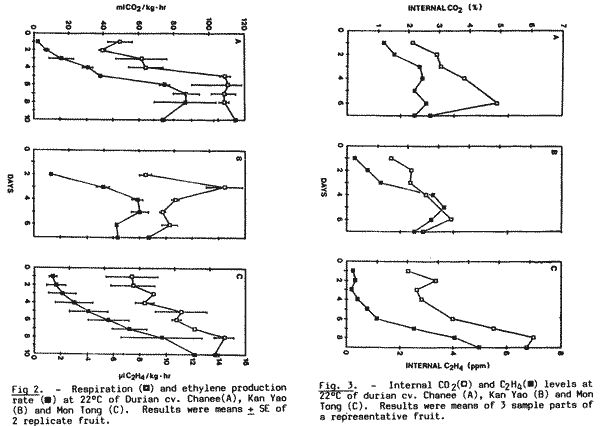

A similar trend in respiration ethylene production was noted among different cultivars with only minor difference (Fig.2.) In 'Chanee' and 'Kan Yao', CO2 and ethylene peaked and plateaued or slightly declined when the fruit was over-ripe. In 'Mon Tong', peak CO2 and ethylene production occurred when the fruit was over-ripe.

The internal CO2 and ethylene concentrations of the fruit also indicated a climacteric rise associated with ripening (Fig.3.). The concentration of CO2, 1. 5-2% at harvest, increased to 3-6% in ripe fruit.

In 'Chanee', the internal ethylene content was 1.4 ppm at harvest. This increased and peaked to 3.0 ppm. 'Kan Yao' and 'Mon Tong' had a lower initial ethylene level, 0.3 ppm, at harvest. In 'Chanee' and 'Kan Yao', maximum ethylene level was found to occur when the fruit began to ripen and before the internal CO2 accumulated to maximum. In 'Mon Tong' there was a steady increase in the internal CO2 concentration in parallel to the increase in C2H4 and both peaked when the fruit was over-ripe. Peak CO2 and ethylene levels were about 7% and 5 ppm respectively.

By experience, 'Chanee' is more exact on when the best consumption date is. A matter of one to two days would make the difference of when the fruit is eating-ripe or over-ripe. 'Mon Tong' is the least demanding as to when to be eaten once ripe, only if one could resist its temptation.

CONCLUSION

Durian undergoes a climacteric pattern in respiration and ethylene production. There was a gradual and steady increase in CO2 evolution in parallel to ethylene production.

Distinct durian aroma which indicated fruit were eating-ripe could be detected one day prior to the respiratory peak. The ethylene peak was associated with senescing tissue or over-ripe fruit. Both CO2 and ethylene production remained relatively high post-climacteric. A similar trend was noted among different cultivars with only minor difference.

The increase in respiratory activities and ethylene production of ripening fruit caused accumulation of CO2 and ethylene inside the fruit. Ripening of fruits could be easily monitored and indicated by the changes in the composition of internal atmospheres as indicated by the present investigation.

Fruit used in the experiment were harvested at a generally accepted maturity stage to ensure fruit of good eating quality when ripe. The almost immediate rise in CO2 and ethylene production of harvested fruit suggested a fairly advanced stage of maturation at harvest. The relative high internal C2H4 level at harvest especially in 'Chanee' (1.4 ppm) indicated ethylene accumulation before harvest. Whether this is physiologically stimulatory and leads to the autocatalytic burst of ethylene production accompanying the ripening process remains to be determined.

Literature Cited

1. ANON. 1975. Underexploited tropical plants with promising economic value. National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D.C.

2. Baldry, J., J. Dougan and G.E. Howard. 1972. Volatile flavouring constituents of durian. Phytochemistry 11: 2081-2084.

3. Martin, F.W. 1980. Durian and mangosteen. p.406-413. In: S. Nagy and P.E. Shaw (eds.) Tropical and Subtropical Fruits. The AVI Publ, Inc. Westport, Connecticut.

4. Mathur, P.B. and H.G. Srivasta. 1954. Preliminary experiments on the cold storage of durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.). Bull. Cntr. Food Tech. Res. Inst. Mysore. 199-200.

5. Saltveit, M.E., Jr. 1982. Procedures for extracting and analyzing internal gas samples from plant tissue by gas chromatography. Hort Science 17(6): 878-881.

|  |

| Fig. 1. Respiration (0) and ethylene production rate at 22°C of Durian cv. Chanee. Results were means ± SE of 3 replicate fruit. |

DATE:September 1989

* * * * * * * * * * * * *