RAMBUTAN SELECTION

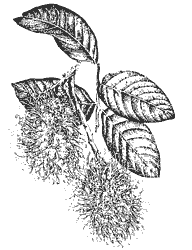

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Nephelium lappaceum

FAMILY: Sapindaceae

INTRODUCTION

RAMBUTANS of course are not the only exotic tropical fruit researched on Kamerunga Research Station. However, the development of rambutan evaluation typifies the research procedures and market perspective which one must consider in order to perform an adequate selection process.

As a rule, the Department of Primary Industries' research programmes follow industry development - a "passive" role where solving industry problems is the main exercise. Occasionally, we get out in front - or at least alongside the industry - as in the case of introduction and screening of tropical fruits. However, these exercises are time-consuming if done on a large scale, require years of perseverance and always suffer the doubt of backing the wrong horse.

The work on rambutan and other tropical fruits conducted at Kamerunga is, in terms of research input and effort, very minor compared with the regional efforts with problems and development studies on banana, coffee, mango, lychee and avocado, etc.

We do not yet know if rambutan will be a significant industry in northern Australia; the long-term economics are not established.

SELECTION PHILOSOPHY

To minimise risk in choosing what product to screen for a future industry, it is appropriate to work backwards from the market end. The questions to ask are:

* Is the product likely to be readily purchased by more than 50% of the population? If not, is there an established ethnic market?

* Is the product attractive, eye-catching and creates pleasure of ownership? If not, has it attributes which will win consumer favour in time?

* Does the product have a satisfactory attractive shelf life and quality? If not, are there, or are there likely to be, techniques to improve this?

Is the crop one which would be harvested in part or wholly during the cooler months of the year? - i. e. April to November when there is much less competition from other excellent 'standard' fruits.

Once it has been established that the crop is likely to have some future on the market, a second set of questions arises:

* Is there diversity in the gene pool (a range of variation in tree and fruit characteristics) which will allow the possibility of selection of superior cultivars for the appropriate Australian climatic zone?

* Are seedlings quite heterozygous (vary from the characteristics of the parents) so that chances of superior seedlings arising are likely without massive programmes?

* Are there serious pest and disease problems with the crop which are very difficult or too expensive to overcome?

* Is production likely to be regular enough from season to season and great enough in total to be economic?

* If production is marginal, will the market price be high enough to be economic?

These are possibly some of the most important questions which a researcher should ask prior to substantial investment in importation of seed and/or clones and setting up screening programmes. This involves assembling and analysing all the world literature on the crop (which is a standard feature of assessing new crops), as well as looking for new varieties of existing crops to extend harvest seasons or seek disease resistance, etc. (e.g. mango).

For storable products, e.g. cocoa, coffee, pepper, etc., obviously many of the parameters are different. However, the same approach is followed.

RAMBUTAN INTRODUCTION PROGRAMME AND AIMS

There are seedling rambutans in north Queensland dating back to introductions in the 1930s by S.E. Stephens and others. However, none have yet proved to be noteworthy cultivars. Nevertheless, we should continue to pursue local seedling selection.

In the early 1970s, a number of people started to introduce cultivars from Malaysia. Since 1974, the Department of Primary Industries has had a major introduction programme from Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines. From both private and DPI introductions some 51 cultivars have been imported and successfully established. The majority are already screened to some extent. The aim has been to ascertain those cultivars with the best combination of fruit quality and productivity. In terms of productivity, it was hoped that screening would uncover cultivars suited to the north Queensland climate despite the fact that the total gene pool is of tropical origin. This premise has been proven correct.

Also, it has been found that quality ratings do not necessarily agree with those in the country of origin. Australian consumers' perceptions of size, colour, texture and testa characteristics are often different to that of Asian people. Also, there has been relatively little gene pool movement between Asian countries and this has limited comprehensive evaluations.

Since a rambutan industry developed in north Queensland before the introduced cultivars had been comprehensively evaluated, it is now important that the recommended cultivars be well-publicised so that inferior ones will not be planted in the future. Sale of inferior fruit can do enormous damage to a developing industry.

CLIMATIC SUITABILITY

Ten years of experience with the crop in north Queensland has established that it is not likely to yield economic crops in areas with mean minimum July temperatures above 15°C.

In areas experiencing minimum means of around 15°C, there is still likely to be occasional absolute minimum temperatures down to 5 or 6°C. Temperatures this low cause defoliation of some cultivars and prohibit satisfactory cropping in the subsequent year.

In reality, cultivars so far screened are only suitable for coastal areas north of Ingham. Further south the trees do survive in many locations but crop poorly. On Cape York, coastal Northern Territory and north-west Western Australia there are lesser climatic limitations and some cultivars unsuitable for the Ingham to Cairns districts may be grown in these locations satisfactorily.

Besides temperature, other limiting factors are water and wind protection. The crop must be irrigated and have good wind protection in order to maximise yield in any locality.

CROPPING PATTERN

The tree is peculiar in that flowering is more seasonal in latitudes above 15°C than below.

Weipa and Darwin (12°C) trees tend to flower in July/August and mature fruit in October/November. Partial crops in February/March also occur but are not substantial.

In the Cairns district, flowering commences in July/August and may continue on different trees or different parts of the same tree until April. Crops are harvested from December to August with a minimum of 3 to 3½ months development period from flowering in August to a maximum of 5 months from flowering in March/April. However, the main crop is in December/January/February. Some cultivars tend to be more seasonal than others but the pattern is not consistent overall. If good growth is maintained, then trees produce regularly each year.

YIELD AND FRUIT QUALITY

The fruit are borne on terminal panicles, the flowers arising on the extremities of main or sub-branches. Mature fruit number per panicle varies with the cultivar in a range from 6 to 45. Pollination is often excessive in North Queensland and there is often a massive natural fruit-thinning drop of green fruit at the three-quarter development stage due to over-crowding on panicles. However, this does not greatly affect yield, although it appears alarming at the time.

Unlike lychee, there is little fruit-splitting or browning at maturity. Maturity is gauged by colour characteristics for each cultivar. Red cultivars do not necessarily reach similar total soluble solid levels at the same intensity of colour. The grower needs to monitor the colour and sweetness of each cultivar.

The number of fruit carried to harvest greatly affects fruit size and there may be up to 50% variation in mean fruit weight from season to season. Fruit weight range varies considerably between cultivars, from 27 g for R169 to 80 g for R139. Excessive numbers of fruit maturing (e.g. characteristic of Penang cultivar) can depress total soluble solids. Most cultivars are best harvested at the 20 to 24° Brix level.

Aril recovery (edible part as percentage of total fruit weight) also varies from season to season, and also varies considerably between cuItivars. R156 (yellow) and Gulah Batu average 50 to 54% aril whilst a number of cultivars range down to 27%.

SELECTION CRITERIA

In arriving at a short list of recommended cultivars the following have been used as the main factors for selection:

1. Attractive appearance

2. Satisfactory fruit size (>35 g)

3. Satisfactory sweetness (Brix 19°)

4. Relative absence of objectionable testa removed with the aril.

5. Ability of trees to withstand a cold spell (7 to 10°C) without major leaf fall.

6. Satisfactory yield

7. Trees cycle crop to crop regularly

Table 1 shows characteristics of recommended cultivars.

POST-HARVEST CHARACTERISTICS AND TREATMENT

The rambutan fruit has a relatively short period of attractive appearance after harvest if subject to high temperatures and air movement. At best, the attractive appearance only lasts 2 to 3 days in the range of 25 to 35°C. The spinterns desiccate and shrivel, assuming a dark appearance although aril characteristics do not change for a longer period. However, if packed to reduce air movement exposure and temperatures are moderate at 15 to 25°C then appearance holds up longer.

A much superior attractive shelf life of a minimum of 7 days is obtained by enclosure in PVC cling wrap film and with temperatures in the range of 5° to 25°C. A post-harvest dip of benomyl (1 000 p.p.m. a.i.) in hot water at 52°C for 2 minutes in combination with PVC wrap extends shelf life even further. However, this treatment is not yet registered for use.

Most rambutans are currently loose-packed (after cutting from panicle) or are placed in single or double layers in 2 to 5 kg boxes. A coloured paper or plastic liner adds to the appearance of the product as well as assisting to prevent desiccation. However, boxes with liners do require longer to pre-cool.

EFFECTS OF PESTS AND DISEASES

Fruit spotting bug (Amblypelta lutescens), mealy bug and mites all contribute to skin deterioration and discolouration of fruit.

Fruit spotting bug and white fly or jassids may also contribute to some fruit drop. Fruit spotting bug damage is particularly noticeable on yellow-skinned cultivars.

The role of the fruit sucking moth is as yet not fully understood. During this summer there has been significant damage particularly on thin-skinned cultivars such as Rongrien.Fruit flies are not pests of rambutan in Australia.

The fruit is attractive to fruit bats, but fortunately not to the same extent as lychee.

A number of fungi have been isolated on fruit during storage. These mainly develop on the bases of spinterns and the stem end, and may accelerate appearance deterioration. However, fruit rots per se do not result.

Article from Kamerunga Horticultural Research Station Centenary Open Day on 21st May, 1987 booklet.

| CULTIVAR | Tree Size (Height) | Tree Spacing (m) | Mean Fruit (mm) Size 1/ | Pericarp Colour | Colour of Spinterns 4/ | Mean Fruit Weight Range (g) | Mean % Aril (Flesh) | Mean Brix° Mature | Cling or Freestone | Testa Objectionable | Aril Crisp or Juicy | Skin Thickness |

| Binjai | medium | 10x10 | 48-40 | orange-red | green tips | 32-41 | 41 | 18-21 | cling | not | crisp | thin |

| Jit Lee (Deli) | medium | 10x10 | 60-40 | crimson-red | green tips | 30-55 | 35 | 20-22 | free | slight | both | thick |

| Rongrien | medium-large | 12x10 | 53-36 | dark red | green tips | 32-37 | 41 | 19-21 | free | moderately | crisp | thin |

| R9 | medium-large | 12x10 | 65-40 | pink/crimson | red | 40-51 | 36 | 20-23 | free | slight | both | v.thick |

| R134 | medium | 10x10 | 56-40 | red/orange | red/green | 34-46 | 45 | 20-22 | free | slight | v. juicy | thin |

| R156 (Red) 3/ | medium-large | 12x10 | 48-40 | pink/red | green tips | 34-43 | 43 | 20-22 | medium | slight | v. juicy | thin |

| R156 (Yellow) | medium | 10x10 | 50-45 | yellow/orange | sl.green tips | 47 | 54 | 19-22 | free | moderately | both | thin |

| R167 | medium | 10x10 | 58-42 | crimson | red/green tips | 37-46 | 34 | 20-23 | free | slight | crisp | thick |

| Silengkeng 2/ | medium-large | 10x10 | 65-40 | red | green overall | 40-48 | 51 | 19-21 | sl. cling | slight | juicy | thin |

1/ Length/width excluding spinterns (spines).

2/ Description does not fit Indonesian description - may be wrongly named. Also, yield data for this cultivar is not well established.

3/ This cultivar imported as R156 but incorrect and true identity not yet resolved.

4/ Except where indicated, the colour of base of spintern is same as the pericarp (skin).

Other Promising Cultivars

R37 - yellow, clingstone.

Gulah Batu - red, slightly clingstone.

R3 - red, slightly clingstone.

DATE: July 1987

* * * * * * * * * * * * *